Apart from the scan of the front cover, and the images taken from the Macfarlane catalogue (see bibliography), the illustrations here come from our own website. They may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, but please credit the photographer or source, and link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and often for more information about them.]

Nothing looks more obviously Victorian than an ornate bandstand like the one on the front of Paul Dobraszczyk's book. Unless, of course, it is a seaside pier, a covered market, a shopping arcade, or a fine set of brackets supporting a station platform canopy, or.... The list could go on, and in every case one material has contributed immensely to the effect — cast iron. Whether as a structural element, or as decoration, Victorian cast iron is still all around us, giving an extra fillip to our leisure activities, our shopping, our journeys and even our recourse to public conveniences: Brighton seafront's "Birdcage" bandstand, featured on Dobraszczyk's cover, was designed in the 1880s as a double-decker affair with conveniences tucked discretely underneath it. For anyone who takes such ingenious contributions to our built landscape for granted, this book will be an eye-opener; and for those who already find them fascinating, it will be a rare treat.

The triumph of cast iron

Glass and iron vaulted roof of the Great Exhibition Hall, designed by Sir Joseph Paxton, 1851: "the first truly public building to fully exploit the constructive potential of cast iron in combination with glass" (6).

Dobraszczyk is the first to admit that cast iron has had its detractors. Such high-minded Victorians as A. W. N. Pugin, John Ruskin found it vulgar and worthless, because mechanically produced — a product of the industrial sector. Whether on show or hidden in the fabric of a building, or added to the surface for decoration, it seemed to them a sort of fake, not genuine. Later, when it was shown not only to rust, but to crack, there were more worrying objections. But the mid-century Crystal Palace, a magically airy space intended as a showpiece to the world, was a wonderful example of its use for construction, at least in engineering projects; and the machine-made ornamental goods on display inside amply demonstrated its aesthetic possibilities. The result was an enormous increase in the range of uses for cast iron, and the intricacy of available designs. So much so that twenty years later the Builder claimed that almost as much cast iron was being produced in Britain as in the rest of the world put together (see Dobraszczyk 13).

Cast iron on show

One of the very elaborate fountains advertised in Macfarlane's Castings (1885): 20.

The almost fantastic abundance and variety of castings is demonstrated in Dobraszczyk's first chapter, which deals among others with exhibitions, catalogues, copyright, "Proliferation Post-1851," rivalries and exports. Among the big producers were Coalbrookdale of Shropshire, which went back to the beginning of the eighteenth century, Carron Co. of Falkirk, which employed the Adams brothers for their designs from as early as 1759; Andrew Handyside, whose company took over the Britannia Ironworks in Derby in 1847, and produced many of our familiar red pillar boxes and railway station roofs; Walter MacFarlane & Co., which took over the Saracen Foundry in Glasgow in 1851; and two foundries set up by ex-employees of Macfarlane — George Smith's Sun Foundry, and the Lion Foundry, both also in Glasgow. And these were just a few of the better known ones. It was an intensely competitive trade.

A Handyside postbox in High Holborn.

If Handyside's name is familiar to some, Coalbrookdale's has also become prominent recently, but for an unfortunate reason: the iconic 309-year-old foundry, which produced the gates for the Great Exhibition (now at the south end of the West Carriage Drive of Kensington Gardens), finally closed its own gates in November 2017. But the most highly reputed foundry, world-wide, was probably Macfarlane's.

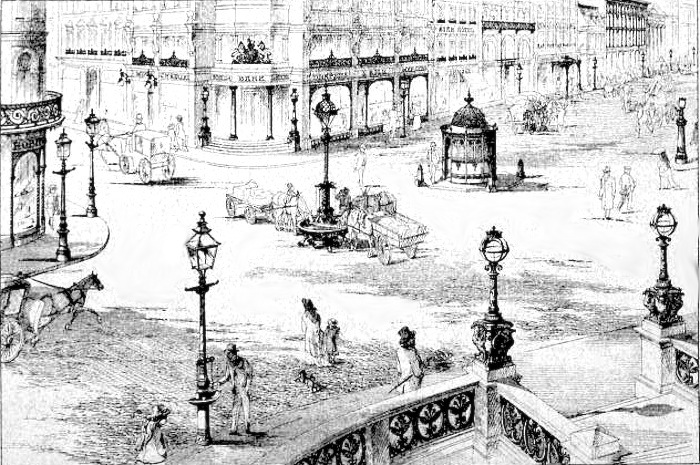

Cast iron in the streets

Left: Frontispiece of Macfarlane's Castings (1885). Right: One of Macfarlane's urinals, advertised on the inside back cover.

Dobraszczyk's first main chapter opens with a page from one of Macfarlane's catalogues, showing just about everything that he discusses in the chapter, including lampposts, urinals, drinking fountains and gates. Each topic is considered in its full social context, so that his discussions are all of much more than niche interest: they will appeal to social historians as well as to industrial archeologists and architectural historians. The section on urinals, for example, is subtitled, "Urinals and Obscenity" and explains that their finish (plain or ornamental) as well as their siting caused much debate, as did the provision of facilities for women, until at the end of the century public lavatories literally went underground — or under the bandstand, as the case might be. However amusing to read now, the histories of these conveniences give us valuable insights about people's attitudes at the time, and how they affected design and planning.

Cast iron at the seaside

Cast-iron rails on Brighton Pier, designed like the bandstand (but earlier) by Philip Causton Lockwood (1821-1908), the town's borough surveyor.

Some street furniture is so distinctive that it creates a whole other world. Dobraszczyk calls seaside resort "ironworlds," and well he might. His next chapter opens with a view of the esplanade at Brighton. What would our favourite resorts be, without their cast-iron shelters, bandstands, railings and piers? Architectural historians have largely ignored these frivolities, yet, as Dobraszczyk says, they marked the seaside out as a fantasy land removed from mundane realities. People entered this land at the station, found their temporary base nearby in rooms with balconies and verandas, and went from the promenade right out across the sea itself, to be entertained in exotic pavilions as the sun went down over the horizon. For some, the proliferation of cast-iron ornament here was not merely entertaining but inspiring. Dobraszczyk has a brief but useful section with the sub-title "Love, Death and Iron on the Pier," dealing with some of the creative work that has grown out of it. The part played by Brighton Pier in the celebrated film version of Grahame Greene's Brighton Rock is especially memorable.

Cast iron and civic pride

Left: Thornton's Arcade, Leeds, with its clock featuring characters from Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe. Right: The brackets supporting the balcony in Leeds City Market are in the form of mythological dragon-like creatures, wyverns.

The last two sections bring us back into town ("Civic Ornament: Arcades and Market Halls") and across country ("Meta-Ornament: Iron and the Railway Station"). The scope here is wide. In the section on town ironwork, Dobraszczyk considers the ways in which it expressed the burgeoning confidence of the industrial Midlands and the north, where new retail spaces approached the allure of palaces — especially of the Crystal Palace. This, we learn, exerted an influence far beyond the construction of Owen Jones's 1858 "Crystal Palace Bazaar" in Oxford Street. What is more, they have long outlived it, and still stand today. Among Dobraszczyk's examples are two in Leeds, Thornton's Arcade, noted for its theatricality (that Ivanhoe clock!); and the Leeds City Markets, with its rows of ornate wyvern brackets supporting the gallery floor and carrying the eye along the length of the hall. These bold and imaginative designs were not simply surface ornamentation or frippery. In some cases with reference to local heraldry, they helped to forge these industrial towns' identities, and assert them to the rest of the country.

Cast iron in the "Age of Steam"

Inside the Great Western Train Terminus at Paddington.

Could it be a case of saving the best until last? The arrangement of station platforms and railway sheds and tracks really did raise the functional to the ornamental — and sometimes even to the sublime. It was behind the frontage that cast iron really came into its own. Dobraszczyk, even-handed as ever, presents Pugin's and Ruskin's objections again. They could not think of "aestheticising" any structures associated with the railways. Pugin had a particular spite against the Euston arch. As stories like Dickens's "The Signal-Man" suggest, for some Victorians the railways even had a nightmarish quality about them. But many others found concentrated in this new kind of ironworld the very essence of progress, connectivity, and aspiration in the modern world.

Dobraszczyk shows how Charles Fox (1810-1874), at Euston itself, began to evolve a distinctive style for this mode of transport. As always, an easy mingling of social history and the arts with more technical observations and aesthetic theory, makes this a pleasure to read. For instance, Dobraszczyk looks at the space devoted to Paddington Station's interior in William Frith's crowded canvas, The Railway Station, indicating that it is much more than a backdrop. These upper parts were painted by Frith's assistant, William Scott Morton (1840-1903), and the way that "the hard line of one of Paddington's longitudinal iron girders" bisects the composition is telling. Was Frith "attempting to humanise the station's mass-produced ironwork" by emphasising the crowded concourse beneath? Or was he associating the ironwork with "the brutal reordering of the natural rhythms of human life" being enacted among the groups of passengers (238)? Dobraszczyk suggests both — perhaps it is the tension between the two that makes the painting so memorable.

Gothic features and Victorian ironwork at Aviemore Station in the north of Scotland.

Due attention is paid here to the great stations of the period: John Dobson's at Newcastle with the first curving train shed, Brunel's and Wyatt's whole new railway aesthetic at Paddington, William Barlow's canopy at St Pancras.... the romance of the railway, so heavily dependent on cast iron, cannot but stir the heart in places such as these. There is much more in this chapter, for example about the standardisation of railway architecture, often with frontages and naturalistic brackets for the platform canopies that brought together "Ruskinian principles with the up-to-date technology of the Crystal Palace" (244). Whether this was a happy or an uneasy marriage is a matter of opinion: Dobraszczyk convincingly presents it as a happy one.

The great Victorian sage reappears again in a last brief chapter, a postscript on rust and decay. Not unexpectedly, Ruskin was only too pleased when cast iron's hard machine-made surfaces began returning to nature. Others, including the architect William Lethaby, found something more in this process — something spiritual, not so much a gradual decomposition as a lingering reminder of an age that has still not vanished.

Dobraszczyk's book teems with ideas and is copiously illustrated throughout, as well as having sixteen colour plates in the middle. Some readers may side with Pugin and Ruskin, and prefer the craftsmanship of wrought iron. But no one could be left in any doubt as to the importance of cast iron in the Victorian age. It has much more to tell us about the visual culture, lives and ideas of the Victorians than we might have expected, and this study of it brings up important issues about aesthetics in the most readable and enjoyable way.

Related Material

- Iron Structures and Victorian Architecture

- Opposing Forces in Victorian Architecture — The Example of St Pancras

- Review of Julie Wosk’s Breaking Frame: Technology, Art, and Design in the Nineteenth Century

- The Seaside in the Victorian Literary Imagination

Bibliography

[Book under review] Dobraszczyk, Paul. Iron, Ornament and Architecture in Victorian Britain: Myth and Modernity, Excess and Enchantment. Pbk. London and New York: Routledge, 2016. 310 + xvi pp. £36.99. ISBN 9 781138310292.

[Illustration source] Walter Macfarlane and Company. Macfarlane's castings : ornamental fountains, park and garden seats, &c. Glasgow: W. Macfarlane, 1885. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Smithsonian Libraries. Web. 28 April 2018.

Created 28 April 2018