Ogmund comes to Midfirth

William Morris, 1834-96, translator, scribe, and illuminator

1871

39.35 x 24.8 cm.

Source: The Story of Kormak

Beckwith, Victorian Bibliomania catalogue no. 59

Collection: Pierpont Morgan Library. Gift of John M. Crawford, Jr.

William Morris penned illuminated manuscripts in the 1850s and 1870s; during both periods, circumstantial evidence indicates that he was aware of John Ruskin's interest in manuscript arts. While an undergraduate at Oxford in 1853 and 1854 Morris avidly read Ruskin's Stones of of Venice II and the Edinburgh Lectures (Henderson, 14-16). [Continued below]

Click on image to enlarge it, and mouse over text below to find links

Courtesy Pierpont Morgan Library

Commentary by Alice H. R. H. Beckwith

Manuscript illumination figures prominently in Ruskin's discussion of the craft worker in both of these books (Hauck 41-59). By the winter of 1856, Morris mastered the illuminator's pen and produced a vellum page of Grimm's Story of the Iron Man in Gothic Revival script with an historiated initial (Fairbank 116). Morris then stopped doing book illumination and became involved in architectural decoration at the Oxford Union building. He did not return to illumination on paper and vellum until 1870-75. However, illuminated manuscripts were important to the Oxford decoration, and Ruskin's library of illuminated manuscripts served both Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Morris as sources of inspiration (Christian 18).

Morris took up manuscript illumination again when Ruskin was promoting it at Oxford. At the beginning of his tenure as Slade Professor in 1869, Ruskin proposed founding a school of manuscript illumination in his inaugural address. Thereafter, Ruskin used illuminated manuscripts as sources of illustrations for his Oxford lectures. On February 23, 1870, Ruskin spoke against proposals to obliterate the Oxford Union murals. Concurrent with Ruskin's defense of the murals Morris began his second group of illuminated works and began again the study of handwriting as a fine art (Mackail, I, 208, 276). Morris produced over thirteen manuscripts between 1870 and 1875, and then, following his earlier pattern, he returned to Oxford, repainted the Oxford Union ceiling, and again stopped painting on vellum and paper.

Alfred Fairbank wrote a detailed analysis of Morris's Kormak manuscript when the William Morris Society used it for their publication, Kormak's Saga, The Story of Kormak the Son of Ogmund in 1870. From studying the manuscript and Fairbank's description, it can be seen that Morris moved beyond the Gothic Revival to Renaissance writing. The style of the 1870 work is similar, but not identical to Tagliente's lettera antiqua tonda (Fairbank, 56). Arrighi's lettera antiqua has also been suggested as Morris's inspiration (Dunlap, 59), and manuscripts by Palatino were also available to him at Oxford. Morris's shift towards a form based on versions of ancient classical models and away from the Gothic is also characteristic of other arts during the 1870s. Ruskin himself had just completed studies of ancient Greek myths of cloud and mist in his Queen of the Air of 1869.

Kormak was one of a group of manuscripts done by Morris in the early '70s in which he used a two-column format and experimented with roman scripts. Trial pages for three other works in the group are bound in with the Kormak: four pages of The Story of Frithiof the Bold, a page of Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla, and two pages of the poem Hafbur and Signy. Morris was deeply involved in his studies and translations of Icelandic sagas at this time. The Kormak and the other trial sheets were bound together in green levant by Douglas Cockerell in 1898, two years after Morris's death, probably when they were given by his widow to Sir Sidney Cockerell.

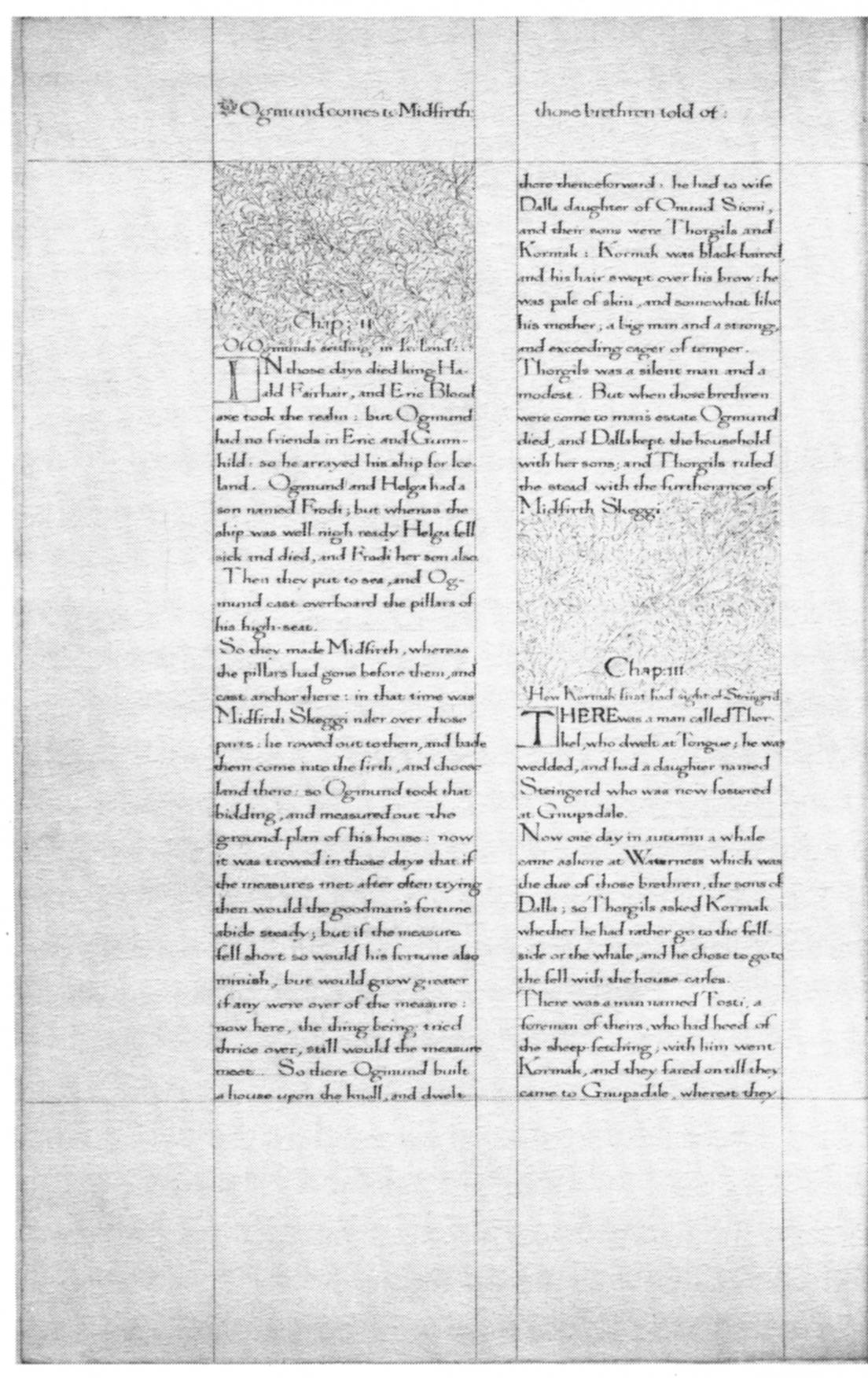

The Kormak manuscript is unfinished. Ten of the first twenty-six pages are decorated with sprays of leaves and flowers drawn in sepia or pencil, but not colored. There are spaces left for additional ornament, as seen around the initial letters on the "Ogmund comes to Midfirth" page. Nonetheless, the floral ornament above Chapters II and III on this page is unlike any illumination seen before Morris, and it finds its equal only in others of his manuscripts and interior painting, wallpaper, and textiles of the 1870s and '80s. The sprays of flowers and leaves in the Kormak consist of slender stems of delicate leaves similar to those Morris repainted on the Oxford Union ceiling in 1875. Even more surprising is Morris's use of a diagonal as the major axis for the leafy sprays, prefiguring designs he used in wallpapers and textiles after 1881 (Parry 58).

References

Beckwith, Alice H. R. H. Victorian Bibliomania: The Illuminated Book in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Exhibition catalogue. Providence. Rhode Island: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1987.

Christian, John. The Oxford Union Murals. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1981.

Hauck, Alice. H. R. “John Ruskin's Uses of Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Impact on His Theories of Art and Society.” PhD Thesis. The Johns Hopkins University, 1983.

Henderson, Philip. William Morris, His Life, Work, and Friends. New York: Mcgraw-Hill, 1967.

McKail, J. W. The Life of William Morris. 2 vols. London: Longmans, Green, & Co. 1899.

Morris, William. The Story of Kormack. 1871.

Parry, Linda. William Morris Textiles. New York: Viking, 1983.

Victorian

Web

Decorative

Arts

Victorian

Bibliomania

William

Morris

Next

Last modified 24 December 2013