[Disponible en français]

orn in 1868 in Glasgow, Scotland, to a police superintendent and his wife, Charles Rennie Mackintosh became interested in architecture and design at an early age. After public and high school in the city, Charles' career as designer, craftsman and architect began when John Hutchison awarded him an apprenticeship at his Glasgow architectural practice where he stayed and worked for five years. In 1889, however, the young Mackintosh joined the partnership of Glasgow's Honeyman and Keppie with the title of junior draftsman. During this period, Mackintosh began attending classes at the Glasgow School of Art under the direction of Francis H. Newberry who had successfully shifted the focus of the school's teachings from those of the classical tradition towards more practical training in the arts and crafts. Throughout the 1890s, Mackintosh's travels and studies in Italy and throughout England as well as his reading of authors such as W. R. Lethaby, David McGibbon, Thomas Ross, and John Ruskin shaped his mature design philosophy. Soon after, by the year 1901, he had risen to partnership in the company of Honeyman and Keppie with the retirement of Honeyman. At this point in his career, Mackintosh's intellectual approach to design had crystallized. In lectures to apprentices at the Glasgow Architectural Association, he outlined his career's central theories by emphasizing the concepts of "honesty of expression in architecture, the need for utility of design, for construction to be decorated, not decoration constructed, and the paramount need for creative independence allied with respect for the past" (Robertson, 6). In his furniture design especially, Mackintosh strived to incorporate each of these concepts.

orn in 1868 in Glasgow, Scotland, to a police superintendent and his wife, Charles Rennie Mackintosh became interested in architecture and design at an early age. After public and high school in the city, Charles' career as designer, craftsman and architect began when John Hutchison awarded him an apprenticeship at his Glasgow architectural practice where he stayed and worked for five years. In 1889, however, the young Mackintosh joined the partnership of Glasgow's Honeyman and Keppie with the title of junior draftsman. During this period, Mackintosh began attending classes at the Glasgow School of Art under the direction of Francis H. Newberry who had successfully shifted the focus of the school's teachings from those of the classical tradition towards more practical training in the arts and crafts. Throughout the 1890s, Mackintosh's travels and studies in Italy and throughout England as well as his reading of authors such as W. R. Lethaby, David McGibbon, Thomas Ross, and John Ruskin shaped his mature design philosophy. Soon after, by the year 1901, he had risen to partnership in the company of Honeyman and Keppie with the retirement of Honeyman. At this point in his career, Mackintosh's intellectual approach to design had crystallized. In lectures to apprentices at the Glasgow Architectural Association, he outlined his career's central theories by emphasizing the concepts of "honesty of expression in architecture, the need for utility of design, for construction to be decorated, not decoration constructed, and the paramount need for creative independence allied with respect for the past" (Robertson, 6). In his furniture design especially, Mackintosh strived to incorporate each of these concepts.

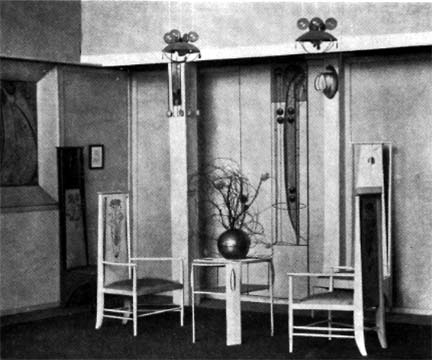

As perhaps his most striking and celebrated furniture design of all, Mackintosh incorporates his famous high-backed chairs into many of his domestic interior design schemes. In his first domestic commission at Windyhill in Kilmacolm in Scotland, his hall chair would set the style and precedent for many of his interiors to come. The high back and stark, uncomfortable appearance of the Windyhill Hall Chair would become an important trademark of his career. Carefully placed within the scheme of the room, these chairs effectively filled an architectural role by both punctuating and defining the interior space. Crafted by Francis Smith of Glasgow under Mackintosh's direction, the chairs appear almost entirely geometric and harsh in form, yet simultaneously draw the mind toward a sense of the organic. Howarth explains that "the tall backs, the oval insets, the pierced patterns of squares and crescents all tell the same story of growth, of upward surging vitality" (Howarth, 50). Similarly, in projects like his Willow Tea-Room, the great number of tall, graceful dining seats arranged together created the appearance of a wooded forest of willows despite the individual chairs' stark, uncomfortable design. In each of these chair designs, the importance lay in aesthetic effect rather than bodily comfort or practicality. In this way, Mackintosh's chairs create a slight feeling of distance and inapproachability in the sense that his interiors serve primarily as a work of art and not an amenable, comfortable living space. This impression accordingly defines the Mackintosh interior as a whole.

Additionally, Mackintosh conceived a striking array of cabinet and bed designs for his series of domestic commissions. Often painted uniformly in white, these pieces, like his chairs, appeared in distinct contrast to any other furniture designs present at the time. In the cabinets specifically, the painted surface "allows the complex curvilinear outlines of the formal design to be clearly expressed" since there exists "hardly a straight line in the whole composition" (Howarth, 52). In this way, he successfully experimented with "the sculptural potential of wood, mashing the resultant unsightly cut crossgrains beneath a surface of paint" (Robertson, 22). Thus, Mackintosh developed a completely new approach to the creation and decoration of domestic furniture in this way. He took such ornamentation even further in works like his Kinsborough Gardens drawing room cabinet in which he utilized paints to adorn the insides of the cabinet's doors with a stylized, yet elaborate depiction of a woman holding a rose. Originally developed as a toy chest at Windymill in 1901, Mackintosh ultimately created the effect of "a fairytale lady's boudoir" for his client Mrs. Robert J. Rowat with this famous piece (Robertson, 22). In this and in other domestic projects such as the Hill House at Helensborough, Mackintosh often maintained the theme of stark, yet organic design paired with uniform whiteness broken up by sparse, but colorful stencils or geometric shapes throughout the room. The artist especially enjoyed employing this particular scheme in bedrooms. In this context, "Mackintosh always made use of luxuriously fitted, built-in wardrobes, and his bedsteads — other than the four-posters are of exceptional interest. They were of heavy construction; the ends being of solid timber, not framed" (Howarth, 106). Thus, Mackintosh's bedroom furniture designs serve as a notable and striking departure from the elements of interior schemes that preceded his work at the turn of the century.

In this way, the furniture of Mackintosh developed with little precedent. The artist created novel works that appear geometric, distant, and stark while simultaneously giving the impression of organic growth and plant-like vitality. The innovative nature of these themes' combination would become the legacy of Mackintosh design, and nowhere may one observe this more clearly than in his schemes for life inside of the domestic sphere in the form of his ground-breaking furniture.

Questions

1. What do you consider the aesthetic effect of Mackintosh's use of white throughout his furniture designs and interiors as a whole? Why do you think he might have employed this color scheme in the bedroom and in other private areas of a household, but not in public spaces like his library of the Glasgow School of Art?

2. How much of Mackintosh's stark, even minimalist design style do you consider a reaction against the interiors of his time? How does this compare to the textiles and prints present in a William Morris-inspired interior? What does this shift say about the changing times, if anything?

3. Does Mackintosh concern himself at all with livability in his interior designs? What elements might you point to in order to demonstrate an attempt at domestic comfort rather than simple, aesthetically-pleasing design.

4. How do Mackintosh's furnished interiors compare to his other works such as his prints and/or architectural designs? Are they more simplistic? If so, for what reason?

Bibliography

Howarth, Thomas. Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement. Routlage, London: 1952.

Mackintosh, Charles Rennie. The Estate and Collection of Works by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. University of Glasgow, 1991.

Created 11 November 2004;

last modified 25 October 2021