This article has been arranged and formatted for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. The illustrations have been placed as close as possible to their original position in the article. [Click on them to enlarge them, and for more information about them, except for the little portrait. [You may use them without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

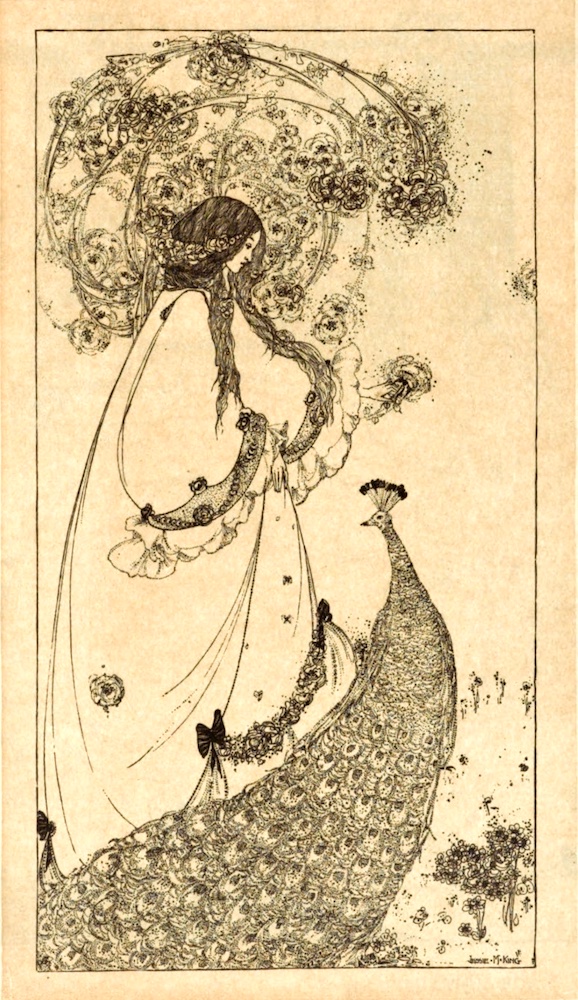

Left: The Little Princess, p. 176. Right: Book-cover by Miss Jessie M. King, p. 178.

"BOOKS are the best friends man can commune with." So says an old writer, and though the statement sums up the influence of the words upon the life and manners of men, there is also another appeal which a book can make, namely, one arising from its treatment as an artistic product, whether by printer, illustrator, or binder. The written matter contained in a book, however beautiful its periods, however deep its teaching, can yet have an added appeal in its presentment as a work of art, whether through its binding or in the illustrations that adorn its pages.

Portrait of Miss Jessie King by M.F. Rowat, p.177.

Many a literary work, worthless though its pages may be, finds a place in a museum or in a library solely because it is enshrined in a covering that makes an artistic appeal to the sense of sight, and numerous examples may be cited where a book would have failed to attract public attention were it not that its pages are explained and illumined by the drawings of the artist called in to aid the writer in the expression of his thoughts. And in the subject of this article, Miss Jessie M. King, we have an artist who has acted in a dual capacity. She has not only illustrated the meaning of prose and poetry by her conception of the thoughts of the poet or author, but has produced designs for the decoration of the covers of books which have given them that added value which true art ever gives where beauty is coupled with utility.

Miss King is a pure product of what may be called the Glasgow School of Decorative Art. Her education has been received entirely at the School of Art of that city, and her personality conjoined with her environment are responsible alone for the work that she produces. Her evolution is a matter of some interest. From the art school point of view, as popularly understood, she was an unsuccessful student. For her, courses of study had no meaning, examinations failed to produce anything but failure, and her opinion of the examiners in the National Competition was not enhanced by the fact 177/178] that their misconception of her aims was patent to her. Her work being unlike that of the ordinary artist, and not bearing the hall-mark of an established tradition in things that are neither individual nor artistic, was naturally condemned by judges taught to believe that a student's business was to be neither individual nor artistic.

The Twa Corbies, p. 178.

Strange as it may seem, she was encouraged in her attitude by those directly responsible for her education; and they have no cause to regret their encouragement. Better a gold medal lost than an artist spoiled, and good it is that in Glasgow, at least, gold medals are no longer to appraise artistic value. A good student is rarely a good prize-winner. To study nature at first hand, and by contact, is to see Nature with eyes directly opened upon her secrets; whereas, to succeed as a faithful follower of a stilted tradition which disallows the personal equation is to put on spectacles belonging to other men, and to study impressions of nature as seen through other men's eyes.

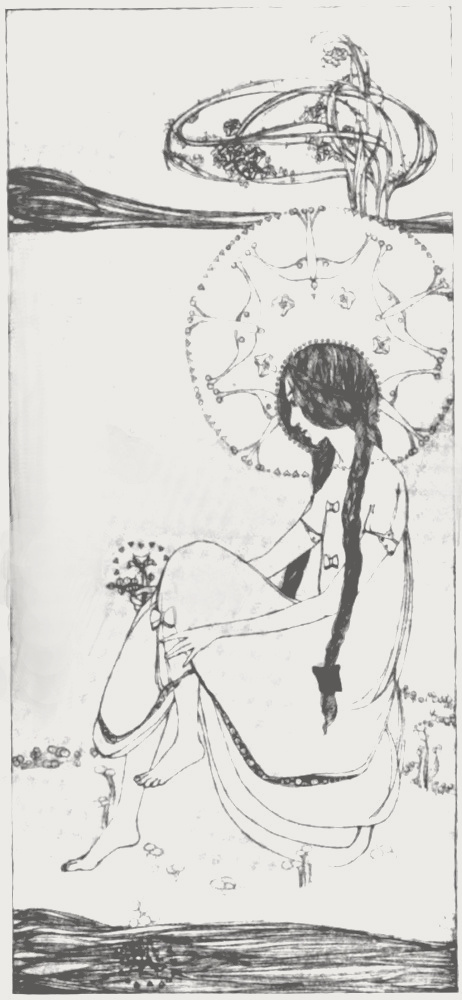

Left to right. (a) The Little Princess and the Peacock, p. 179. (b) Illustration for The Magic Grammar, p. 181. (c) "La Belle Dame Sans Merci Hath Thee in Thrall" from a drawing by Jessie M. King, p.182.

Miss King would persist in seeing things and representing them entirely with her own vision, and absolutely in her own way. Hence her failure as a South Kensington student, and her success as an artist. Miss King's deep and artistic love of Nature brooks no interference. Like a person living in this world, but not of it, Nature has for her a symbolism and a meaning which comes only to those who unreservedly yield themselves to Nature's influence, and pry with loving eyes into the secrets of her working. To this artist, a rose-bush is not a plant bearing flowers, but a bower whose green columns bearing coloured lights make a palace where bright beings walk dreamily about; a bird is a messenger bearing words of import for her alone; the changes of the day each tell their tale and, to her, beasts and birds are friends whose lack of words yet leave nothing to be comprehended. Hence, when Miss King found herself called upon, as an almost first essay of her powers, to illustrate Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book, the fact that the animals spoke and Mowgli understood their speech, was to her no matter of wonder, for she had long been in closest sympathy with Nature, had listened to the language of the woods, and communed where he who had not the secret had found nothing but silence. And this intense love of Nature is translated into the language of line by an imaginative conception, and a poetry and [178/187] daintiness of treatment rarely met with. Thought and execution form a complete ensemble, and the stamp of a strong personality is seen on everything that is produced.

Design for a book-cover by Jessie M. King, p.183.

The drawings are the artistic expression of an artistic spirit, but, in addition to this, we find Miss King's work instinct with poetry and imagination, and there would seem to exist in her delicately balanced temperament a perpetual endeavour to express the spirit of the thing, to pass through and beyond the outward and merely physical limitations, and to search the essential life and reason which animate it. In some of her drawings, Miss King discovers that what men value as substances have a higher value as symbols, and to her Nature presents immense and mystical shadows of spiritual things. Her imaginations are more perfect and more minutely organised than what is seen by the bodily eye, and she does not permit the outward creation to be a hindrance to the expression of her artistic creed. The force of representation plants her imagined figures before her; she treats them as real, and talks to them as if they were bodily there; puts words in their mouths such as they should have spoken, and is affected by them as by persons. Such creation is poetry in the literal sense of the term, and Miss King's dreamy and poetical nature enables her to create the persons of the drama, to invest them with appropriate figures, faces, costumes, and surroundings; to make them speak after their own characters. They speak to us, and their depth of perception appeals to us not less than their charming novelty of invention and spontaneity. It is in vain to say that most of the original work of the last ten years has been executed under the influence of the genius of Aubrey Beardsley. He saw one aspect of Nature, and that often as she appears vitiated and corrupted by the influence of a city. But there are those, and Miss King is among them, to whom Nature comes in the perfume of the flowers and the songs of birds, and is ever seen with the light of the country sun in the eye, and the wind from the hills filling the nostrils. Expression as a technical treatment is a matter of little consequence, for line, as line, is limited in its application, and the Japanese can yet teach the European the secrets of a pen, and the symbolic meaning of colour. And, further, to Miss King comes also that love of fellow man which Coleridge has so beautifully expressed:

He prayeth well who loveth well

Both man, and bird, and beast.

Left to right. (a) Frontispiece for L'Evangile de l'Enfance by Jessie M. King, p. 185. (b) Pen-drawing, p.186. (c) Book-plate, p.186. (d) Book illustration, p.186.

The deep and pathetic ballads of her native Scotland, the works of other poets, the fairy tales which are the common heritage of our Aryan stock, the naturalism of Zola, and the mysticism of Maeterlinck all find in her a ready response. And whether illustrating their pages, or decorating the covers of their works, the hidden meaning stands revealed, and the artist translates into the beauty of line and form the thoughts and ideas which the pen has expressed.

The Romance of the Swan's Nest,

by Jessie M. King, p.187.

And it is no mean task to present to the reader illustrations of a poetic or imaginative text which shall equal the power of that text itself. From how many of our authors do we wish the disturbing illustrations [187/188] away, — to how many volumes do we not grudge the richness lavished on their covers? But in Miss King’s art it is never so. We treasure the book she has decorated because its contents have an added value from the beauty of their exterior, and we feel as we read a book she has illustrated that it would be the poorer were her drawings, with their deft and dainty expositions, not a part of it. Miss King’s art, however, needs but few words to explain and emphasize its intentions, and proofs are to be found in the accompanying illustrations of the practical truth of this appreciation.

Bibliography

Watson, Walter R. "The Work of Miss Jessie King." International Studio Vols. 17-18 (1902-3): 177-88. HathiTrust, from a copy in the University of Minnesota. Web. 13 June 2024.

Created 14 June 2024