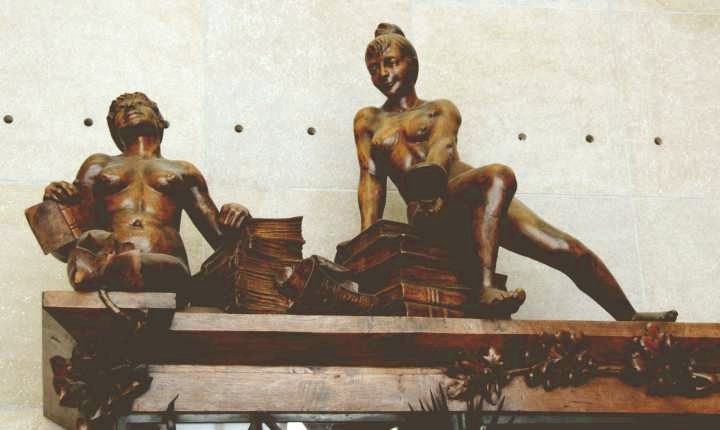

Two female figures on a Art Nouveau Bookcase and Display Cabinet. François-Ruper Carabin (1862-1932). Collection of the Musée d'Orsay [No. O872]. Photograph by George P. Landow.

Other views

- Entire bookcase

- Single female figure

- Bas relief with two nudes

- Wrought iron latch in form of a mouse

François-Ruper Carabin's elaborate cabinet for books, art objects, and prints (1890), proved one of the weirdest and hardest to decipher works I encountered in the d'Orsay. It seems fairly obvious, particularly after comparing this piece to other works of sculpture in the museum, that one of the women holding a book represents poetry and the one with the mirror in her hand represents nature (if she were looking at herself in the mirror it would be the Venus-mirror or vanity theme instead). Perhaps the figure at the right end is philosophy, since the three often appear together, but the figures, however beautifully carved are all strange and whimsical, as is the latch in the form of a little mouse. The two naked women at the door — one using a printing press and the other looking at a portfolio of prints or drawings — show that the large door covers prints, but what the woman at lower right and the heads at the left all seem quite ambiguous.

According to Alexander Kader's essay in Greenhalgh (which includes an excellent photograph of this piece from another angle without the reflections, p. 250), Carabin considered this a work of sculpture meant in the medieval manner — or what he considered the medieval manner — that would combine fine and applied art; in other words, he thought he was reforming sculpture, not furniture. Kader identifies the figures at left as vanity, intemperance, greed, folly, and hypocrisy while the figure at right represents ignorance. The three figures perched on top of the cabinet, he says, are truth, knowledge, and contemplation, but, if so, they neither fit the iconographical tradition, nor can one readily identify any single woman with a particular virtue, unless what I have identified as a personification of nature could be taken to be truth, as in "truth to nature."

Bibliography

Kader, Alexander. "The Concentrated Essence of a Wiggle: Art Nouveau Sculpture" in Art Nouveau, 1890-1914. ed. Paul Greenhalgh. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000. Pp. 250-61.

Last modified 22 September 2008