“Although fashion magazines and etiquette manuals typically advocated simplicity as the guiding principle in Styles, even deepest mourning attire could conform to every nuance of fashionable dress, replicating not only its silhouette but also its ornate forms of embellishment.” — from one of the labels at the exhibition.

Left: The sign for the exhibition that runs from October 21 2014 to February 1, 2015, which one sees coming down the stairs from the Egyptian galleries. Right: A gathering of English and American mourning clothing from the first half of the nineteenth century.

Once again the Met, a museum justly known for its large blockbuster exhibitions, does a masterful job with a small, one- or two-room show, just as it did recently with Making Pottery Art, the exhibition of works from the Robert A. Ellison Jr collection of which Harold Koda and Jessica Regan were the curators. In the hour and a half that my wife and I spent at Death Becomes Her, we noticed that other vistors (one of whom dressed herself and her daughter in black) lingered for a considerable length of time, and they did so because the exhibition's combination of major items, exemplary explanatory labels, and excellent design created a fascinating combination of the aesthetic and the educational.

Mourning Parasol. 1895-1900. Black silk, wood, metal, tortoiseshell The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Rachel Trowbridge, 1960 (2009.300.2478) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Click on image to enlarge it.

Throughout the chat labels linked individual items not only to the history of dress design but also to matters of social class and fast-changing technology. For example, the text accompanying a black taffeta parasol on display in the second smaller room first explains that the taffeta is overlaid with mourning crape, surmounted by ruched mousseline de soie and bands of lace. It then describes how the fabric was mass produced by manufacturing processes developed by mid-nineteenth century: “In order to achieve the fabric’s distinct texture and finish, undyed gauze made from highly twisted silk yarns was first passed through a pair of rollers; one was engraved with a pattern that was impressed upon the textile. Next the fabric was soaked in hot liquid, relaxing the twisted threads and creating a crimped effect. It was then dyed and dressed with a gum or starch, giving it a stiff body and the dull appearance required of deep mourning.”

Queen Victoria in Mourning

For readers of the Victorian Web, the obvious high point would be Queen Victoria’s own mourning dress from late in her reign. Like several of the most important items in the show, it came from the Brooklyn Museum ’s costume collection within the last few years, and it is good to report how well — and how usefully — they take their places in their new home.

Left: British mourning dress originally warn by Queen Victoria. 1894-95 Black silk taffeta, black silk ribbon, black silk lace, black silk crape. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (2009.300.1156a,b). The exhibition label points out that although the dress lacks the “dramatic reshaping of a high-fashion understructure, the dress incorporates some of the fluidity of 1890s fashion in the form of sleeves and trimming of pleated mouseline de soie.” [another view]

Left: British evening dress. c. 1861. Black moiré silk, black silk lace, jet. Lent by Roy Langford (C.I.L.37.1a,b).

Right: Mourning Dress, 1902-1904

Black silk crape, black chiffon, black taffeta

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of The New York Historical Society, 1979

(1979.346.93b, c). These two photographs and the one immediately following: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis.

Henriette Favre (French). Evening Dress of mauve silk tulle, sequins worn by Queen Alexandra. 1902 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn, 1937 (C.I. 37.44.1)

The museum label points out that the evening gowns that Queen Alexandra wore the year after Queen Victoria's death, embody the loosening of the rigid prescriptions of earlier decades and “the opulence of court dress in tones of half mourning. On the gown by Henriette Favre, a couturiere whose clients included ladies of the English court and American women of style, silk tulle is densely embroidered with sequins in varying shades of mauve, forming motifs of bow knots and scrolling ribbons that cascade from bodice to hem. This gown, and the similarly composed example of black tulle embroidered with deep purple sequins, demonstrates a dramatic shift from the sober mourning attire of Queen Victoria.”

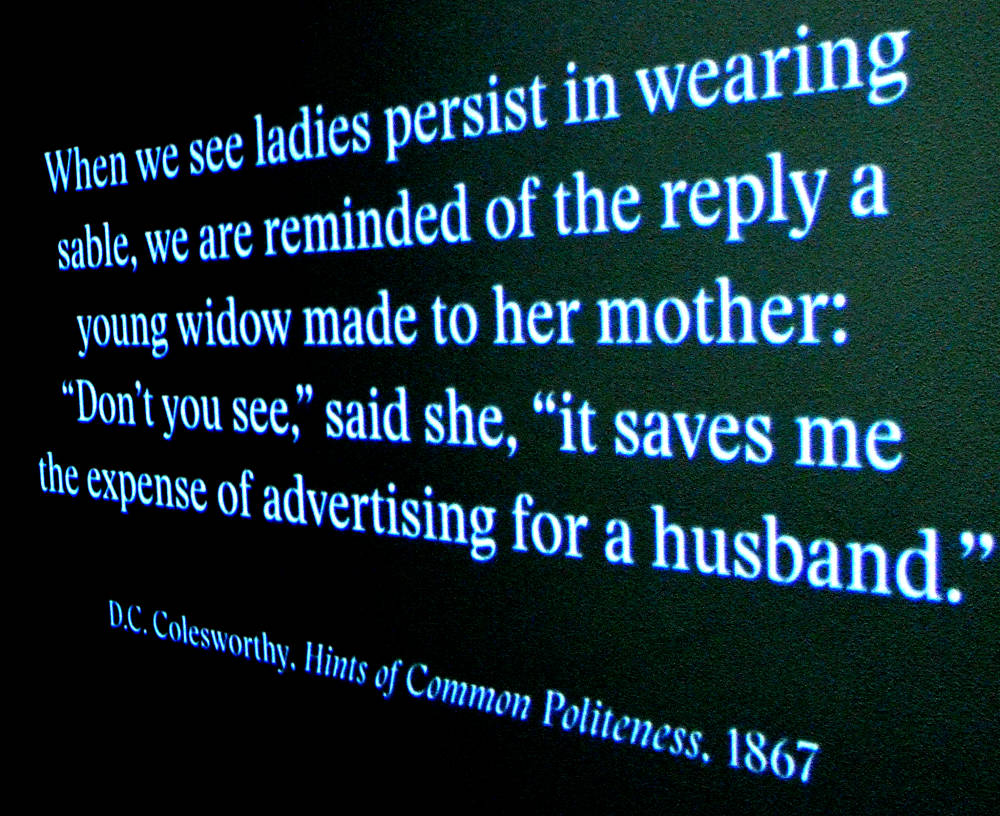

Death Becomes Her made good use of the the room’s walls, projecting various nineteenth-century texts upon them. At the right above we find an 1867 remark about the perhaps unexpected virtues of mourning attire, and at the one at left we catch a ghostlike figure moving across the quoted passage, in this case one complaining about the cost of having to outfit oneself in mourning clothing.

The exhibition’s smaller room, which serves as an auxiliary footnote to the costumes, was dominated by a delightful series of Gibson cartoons that commented somewhat caustically upon the fate of a beautiful, wealthy young widow. These beautiful drawings, which appeared in Life magazine around 1900, look askance at the culture of mourning while other items on display, such as photographs and paintings of the dead and a few examples of mourning jewelry, emphasize the seriousness of bereavement and grief. The display of jewelry struck me as a bit disappointing, not least because it was a little tame. Given the large amount of hair jewelry that survives, I would have expected to see some pieces, such as rings and bracelets, made almost completely of hair of the deceased. Of course while I was looking at the jewelry, I overheard a woman telling her mother that the items on display “creeped her out” and that she wouldn't want to wear a piece of jewelry with the hair of a dead person. Her reaction shows how differently we approach the pain of loss than did so many Victorians. But although many visitors to Death Becomes Her might not find all the conventions of Victorian bereavement appealing, everyone we saw found the beautifully preserved costumes enormously interesting.

Gallery View, Anna Wintour Costume Center, Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Click on image to enlarge it.

Related material

- The Art of Mourning, the Museum of Morbid Anatomy, 2014-2015

- Mourning Becomes Her — A notice of an exhibition at the Saratoga Springs History Museum

Created 29 December 2014