This is an extract from Joanna Williams's book, Manchester's Radical Mayor, Abel Heywood: The Man Who Built the Town Hall (see bibliography), which the author has kindly shared with the Victorian Web. It has been formatted and illustrated for the website, and linked to other material on it, by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.

The committee got a rough ride in March 1876 with regard to the decoration in the building. At the council meeting of 1 March they were taken to task for not offering the decorative work on the ceilings in open competition in Manchester. Alderman Grave defended the use of "special men to do special work," and in response to a complaint by Councillor Stewart, Joseph Thompson had to justify fees paid to Waterhouse as a commission on the special work, on the grounds that he "would engage the best men to do the work required in the best manner." Then Abel waded in to support his colleagues, and added pointedly that "while the sub-committee had entire confidence in the architect, he thought the council should have confidence in the committee." He added that "the remark made by Mr. Stewart was most ungenerous." The critics were again silenced, for now (Manchester Guardian, 2 March 1876; Manchester Courier, 2 March 1876; Manchester Times 4 March 1876).

However, the wider public took an interest in this issue, and took exception to the idea that Manchester artisans were not up to the job of special decorations. On 7 March the Manchester Courier published a letter from "A Practical Man" in support of Councillor Stewart and the other detractors, and describing the decision about the ceilings as "the squandering of the ratepayers’ money." He argued that it was not special work and that there were tradesmen in the city who were well capable of doing it. Indeed, he made the cogent point that he had seen "one or two of the worthy aldermen on the platform advocating scientific and technical instruction to our youth, and yet they show their inconsistency in what they advocate by sending work out of Manchester which could be executed as well by an apprentice or an art student under the guidance of an experienced architect or designer." It was indeed true that Abel himself had been a keen proponent of local skills, and did not seem to be putting his ideals into practice. The Practical Man ended with a strongly worded reminder that the electors would have their say about such "incompetence" and "wasteful expenditure" at the next municipal elections. (Manchester Courier, 7 March 1876).

The public hall.

Likewise, the murals continued to excite discussion. It had been explained in January 1876 that paintings on the wall panels in the public hall would be commissioned, and the suggested theme at this point was "the pastimes of England." They were to be painted at a very reasonable price of £150 per panel by Henry Stacy Marks, then painting murals at Eaton Hall. However, Marks withdrew when his work was not definitely accepted. Frederic Shields and Ford Madox Brown, one of the great Pre-Raphaelite painters of the day, by June 1877 had agreed to undertake the work. In August a deputation from the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts pressed that the murals, apart from those in the public hall, should be done by Lancashire artists and that the artist J.D. Watson should oversee the work. Waterhouse considered their intervention "rude and uncalled for," and Brown’s reaction was even more hostile and offensive: "It was one thing for us to work in company with some of the finest artists in the country, and another to form part of the group of nobodies such as there was talk of giving the rest to.... Waterhouse agreed to state to the committee that should they insist on giving the other rooms to these Manchester beginners it was likely I would refuse to co-operate" (Trueherz 169-71).

The public hall murals were not begun until April 1879. Shields withdrew and Brown carried on the work until 1893; the twelve panels of the public hall became the most famous of the wall-paintings. The work in some other rooms was never achieved, despite Waterhouse’s dogged campaigning almost to the end of his professional career; he was still writing to the mayor about it as late as 1895. Brown agreed to do all twelve panels in the public hall at an initial cost of £275 each, which was raised to £375 by the council in 1884, when Abel argued that his work, considered to be very good indeed, had been undervalued, and that there were difficulties created by the usage of the building and the inconvenience of the public peeping in. An attempt was made to give the artist some privacy by the erection of a canvas booth around him which he said he found "very comfortable" (Manchester Courier 5 January 1884; Treuherz 177).

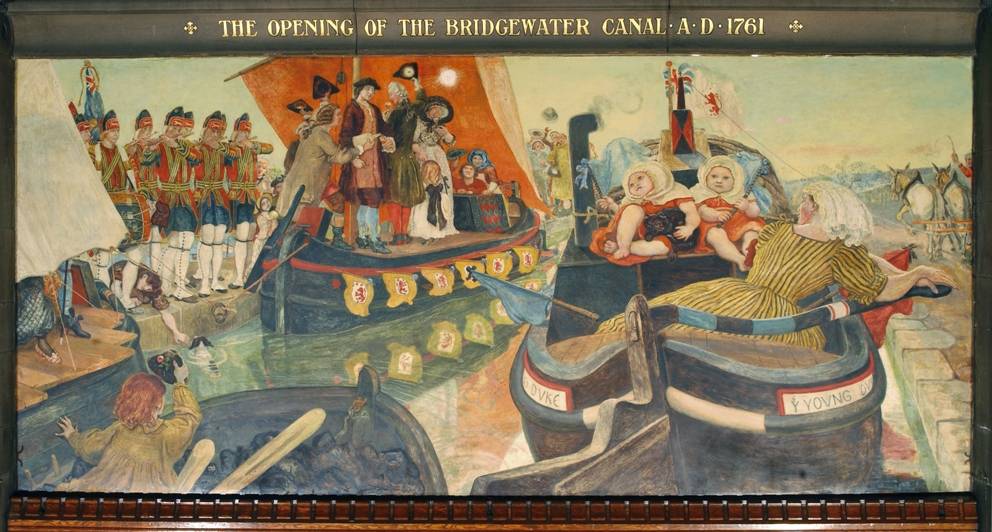

The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal.

The subjects were supposedly celebrating Manchester’s proud history, but in some cases the "history" was more mythological than factual, as W.E.A. Axon was at pains to point out. Brown, a radical sympathiser, had hoped that Peterloo would form the climax of the series, but this was quashed by the Decorations and Furnishings Sub-committee and the opening of the Bridgewater Canal was substituted. It is not recorded how Abel and his allies felt about the omission of one of the fundamental events of radical Manchester. Even Brown’s handling of the new topic did not please some of the council, because as a populist he focused overmuch on the bargee’s wife and children. Some panels were not related directly to Manchester’s history – the baptism of Edwin took place in York, but it was used to show the Christian heritage of the city. The council were unaware, according to Joseph Thompson who played a big part in overseeing the work, that the last panel painted, Bradshaw’s Civil War defence of Manchester, was executed after Brown had suffered a stroke and lost the use of his right hand. The work lasted in total fourteen years; it was Brown’s last big commission and he died soon after completing it in 1893, much affected by criticisms of the murals. He was not to know that his murals "may have established the city fathers as 'admired leaders of public art patronage' (Balshaw)." [181-183]

Links to related material

- Manchester Town Hall (exterior view)

- Manchester Town Hall (some exterior details)

- Interior of Manchester Town Hall

- Ford Madox Brown's murals in the Great Hall

Bibliography

Treuherz, Julian. "Ford Madox Brown and the Manchester Murals." In Art and Architecture in Victorian Manchester. Ed. John H. G. Archer. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986. pp. 169–71.

Williams, Joanna M. Manchester's Radical Mayor, Abel Heywood: The Man Who Built the Town Hall. Stroud, Glos.: The History Press, 2017.

Created 15 April 2020