Many thanks to Ramachandran Venkatesh, who has kindly contributed all the colour photographs here, and the main part of the commentary. Readers may wish to see the original version on his own "Heritage Traveller" website, and explore that website further. George P. Landow added the introductory quotation from Stuart Durant, and Jacqueline Banerjee added the historic picture, the picture captions and the last paragraph, and formatted this entry. You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one. [Click on all images for larger pictures.]

The Victoria Terminus, Bombay (now Mumbai's Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus). Designed by Frederick William Stevens (1847-1900), and completed in 1888, the massive sandstone building has been described as "a sort of secular cathedral ... stupendous ... a statement of pride" (Morris 133). It is important to note that Stevens was assisted by Raosaheb Vaidya, Assistant Engineer, and M. M. Janardhan, supervisor (Howard 82).

Introduction

Left to right: (a) The Victoria Terminus in 1888, shortly after opening. Source: Library of Congress Online Gallery, Digital ID 4a02613. (b) A British lion on the façade proudly holds the shield of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR). (c) An exammple of the fine stone-carving on the façade.

The station was named the Victoria Terminus on the occasion of Queen Victoria's Jubilee in 1887. In 1996 it was renamed the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in honour of Chhatrapati Shivaji (1627-80), scourge of the Mughals and founder of the Mahratta empire, which was finally extinguished by the British in the early nineteenth century. Mumbai is the capital of Maharashtra and Shivaji is the state hero. The station — the original terminus of the Central Railways — was designed by Frederick William Stevens, born in Bath, who joined the Indian Public Works Department at the age of twenty. It is said to have been influenced by George Gilbert Scott's Gothic Midland Hotel, although it incorporates fine Indian carving and decorative features. John Lockwood Kipling (1837-1911), father of Rudyard Kipling, was Director of the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay — the first modern art school in India. The institution promulgated the idea of amalgamating Indian and Western traditions, which was part of government policy. The Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus was put on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2004 — the first building of its kind. — Stuart Durant

Exterior

Left to right: (a) Statue of Progress, fourteen feet high, carved by Thomas Earp, at the apex of the central dome (see Davies 175). (b) The roofline bristling with turrets, spires and gargoyles. (c) Close-up of gargoyles.

The erstwhile Victoria Terminus is a grand structure.... It serves as a major terminus for suburban trains as well as long distance trains, the two sets being separated into the old platforms touching the heritage building, and the new platforms down the connected corridor. The early history of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR), the organisation that owned the terminus, is by itself a history of Indian railways. It was, after all, from Bori Bunder where the first passenger train went to Thane amidst great fanfare and continued to grow. The CST building serves as a living office for the Central Railway, and the intricacy of the work done by the JJ School of Architecture on its walls, pillars and spires, is awe-inspiring.

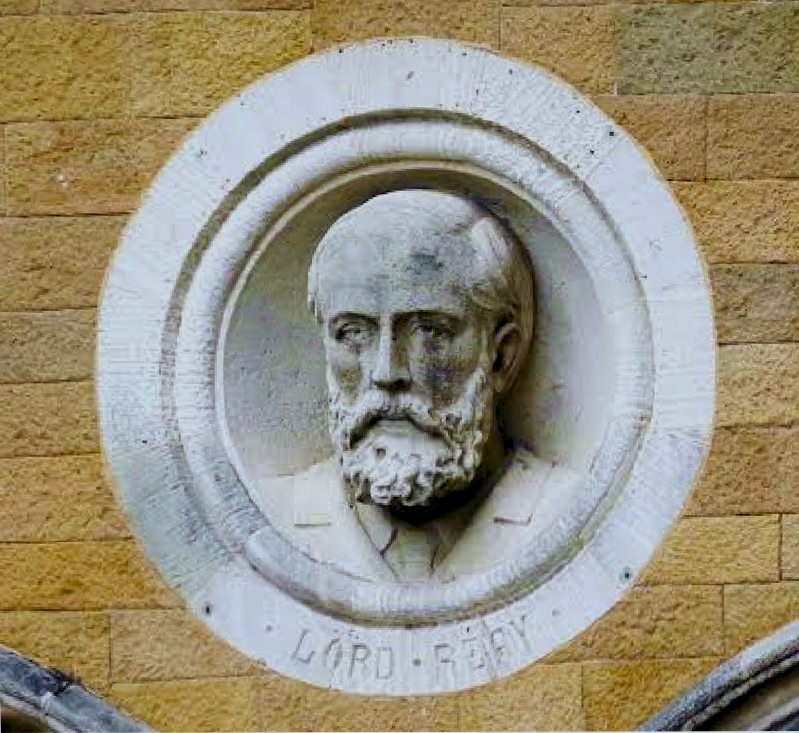

Three of ten medallions, also carved by Earp, on the façade, showing, left to right: (a) Colonel James Holland, who was reported as having presided over the general meeting of the GIPR in December 1886 ("Railway and Other Companies"). (b) Sir Jamsetjee Jijibhai Bart. (1873-1859; his name is variously spelled), the merchant and generous benefactor whose name is borne by the JJ School of Art mentioned above. (c) Lord Reay (1839-1921), whose statue stands outside the JJ School of Art, and who was governor of Bombay 1885-90 (Steggles and Barnes 228; Satow and Brown).

The great people associated with the bringing in of the railways, either Directors of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway or other prominent people of that age, are honoured on the walls with busts in a series of medallions. The city of Bombay (as it was called then) was being developed by the British government as a great port and trading centre and the Indian populace had a great role in contributing to the same, both in terms of economic participation, and by actively contributing to the construction of great public buildings, the port and other civic amenities. After the government of the East India Company ended in 1858, a great shift was made in the Victorian age from establishing new laws that promoted a modern codified law (like the Indian Penal Code, the Negotiable Instruments Act etc.), and public institutions (the High Court, the University, the Public Works Department etc) towards the creation of a new set of civic amenities (including the BMC and Crawford Market) and the Vihar water works. This was accompanied by a lot of public architecture on a grand scale, including the Victoria Terminus/ CST. The period following the change of government also witnessed the breaking down of the Bombay Fort by the new authorities to create a new city.

Another three of Earp's medallions on the façade showing, left to right: (a) Jagannath Shankarshet (1803-1865), another wealthy Hindu businessman and philanthropist (see Venkatesh's site mentioned in the headnote). (b) The Marquis of Dalhousie (1812-1860), a "committed technological modernizer" (Kerr 18) and Governor-General of India, 1848-56. (c) Sir Bartle Frere Bart. (1815-1884).

The faces depicted on the CST wall honour great people of diverse backgrounds and positions (and nationality) who contributed to the creation of the new city. In today's age of dividing everyone from the past between "good" and "bad" persons it may be difficult to comprehend the composite culture and governance promoting economic benefit of its citizens (through development of the port, rail, trading and banking institutions put together), but it is a fact that our city was a hybrid culture of forward-thinking people both from Indian communities and from the British Presidency government of those days who strove to create a modern port and trading city. Many Indian philanthropists contributed huge amounts to institutions set up by the government directly or indirectly. It was, after all the creation of the Urbs Prima in Indis. — Ramachandran Venkatesh

Interior

Left to right: (a) The "Star Chamber" or main booking hall in the north wing, with its pointed Gothic arches and vaulted ceilings. (b) Another view, from an upper level. (c) The sweeping staircase up to the chairman's offices.

Left to right: (a) Detail of a stone-carved rampant lion on a newel post, holding a shield. Seen on it here are two modes of transport: in the top left quarter, an elephant, and in the top right, a steam engine. (b) Another view of the great staircase. (c) The awesome inner dome, with its astonishingly and exquisitely detailed stone-carving, complete with stained glass windows.

According to the RIBA website, which features the station as one of its important "Buildings around the World," the station was constructed on a C-shaped plan, with two wings either side of the central dome, the north attached to the train-shed, and providing the waiting rooms and other passenger facilities, and the south housing the offices for the staff, police, postal services and a library. There have been changes since then, notably an internal rebuilding in 1921 (see Morris 133), but the ground floor of the north Wing, known as the Star Chamber from the motifs in the floor tiling and, previously, the stars painted on the canopying ceiling, is still used as the main booking office. This spectacular space, enriched with Italian marble and polished Indian stone, goes back to 1888. Architectural historian Philip Davies is not totally uncritical, finding a want of verticality in the long flanking wings, and wishing the towers at each end were higher. Nevertheless, he considers the station building, as a whole, to be "the supreme example of tropical Gothic architecture ... a riotous extravaganza of polychromatic stone, decorated tile, marble and stained glass," seeing it as "one of the architectural treasures of India" (173). The view is very widely shared. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Related Material

- Progress and other sculptures by Earp here

- Indian Railways: A Chronology

- Railways in British India: An Introduction to Their History and Effects

Bibliography

Davies, Philip. Splendours of the Raj: British Architecture in India, 1660-1947:. London: Penguin, 1987.

Howard, Stephen Goodwin. Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai. MA thesis presented to the Department of History at the University of York, 2012. Web. 20 June 2016.

Kerr, Ian J. Engines of Change: The Railroads that Made India. Westport, CT.: Greenwood, 2007.

Mason, Philip. The Men Who Ruled India: The Founders. London, Cape, 1953.

Morris, Jan.Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

"Railway and Other Companies." The Times. 18 December 1886: 11. Times Digital Archive. Web. 20 June 2016.

Satow, E. M., rev. P. W. H. Brown. "Mackay, Donald James, eleventh Lord Reay and Baron Reay (1839–1921), administrator in India and educational administrator." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Onloine ed. Web. 20 June 2016.

Tindall, Gillian. City of Gold: The City of Bombay. New Delhi: Penguin, 1992. [Tindall has an evocative reference to the station's "celestial vaults," and calls it "St Pancras Station beautifully crossed with Mohgul Mausoleum," 13.]

"Victoria Terminus." Architecture.com (RIBA). Web. 20 June 2016 (no longer available, 30 September 2023).

Last modified 11 October 2017