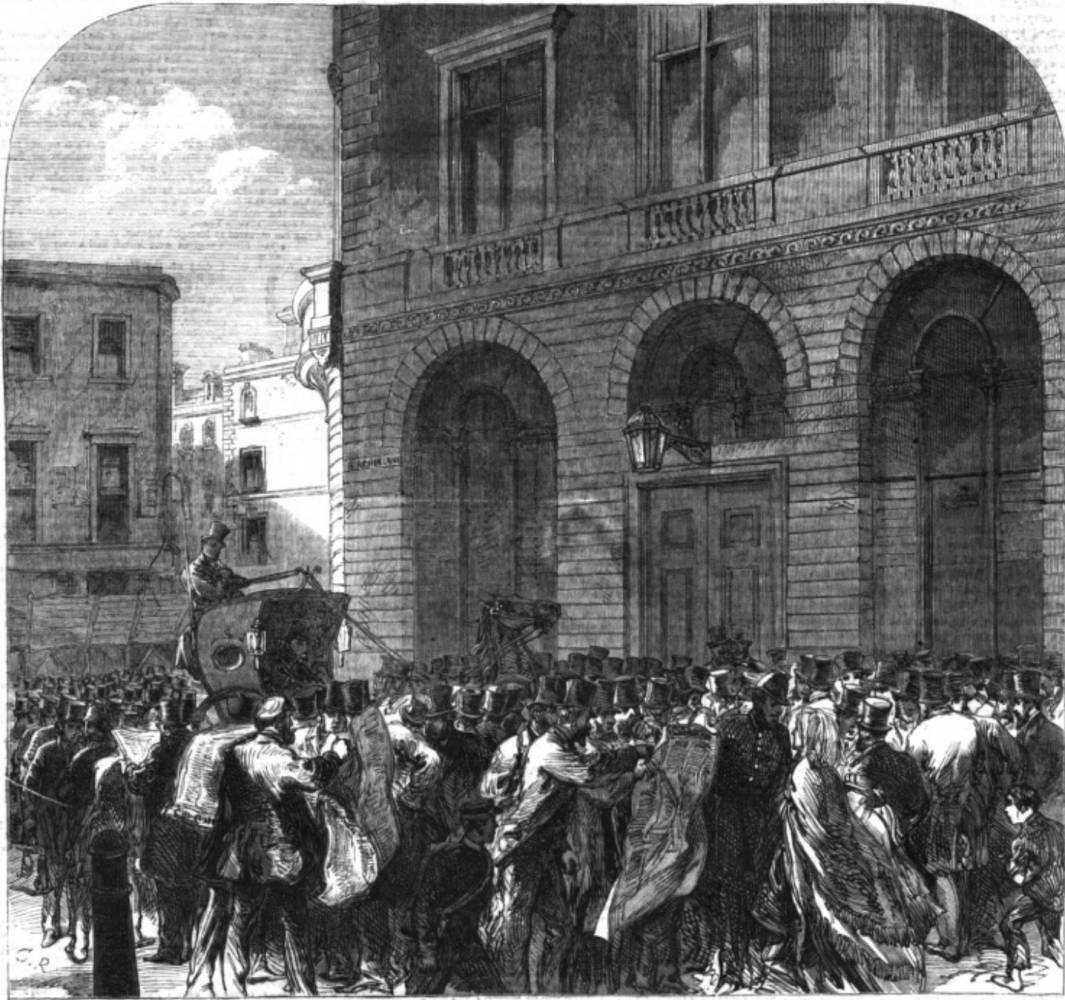

The Panic in the City: Scene on Lombard-street on Friday

1866

Source: Illustrated London News.

“It seemed as if the whole commercial and monetary system of the country would presently collapse.”

Click on image to enlarge it.

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Hathi Trust Digital Library and The University of Michigan Library and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Article above the illustration and on following page

The City will not soon forget Friday, May 11, 1866— “Black Friday” it has been designated with great propriety. On that day the monetary unsettledneas of some weeks past, which the day before had risen to a gale, culminated in a tornado, the frightful force of which was far beyond all precedent within memory of the living, and which, if it had continued four-and-twenty hours longer, seemed likely to involve in disaster and wreck all the money establishments of the country. Happily, and, let us add, owing in great measure to the moral courage and promptitude of the Government, the fury of the commotion was as shortlived as it was violent, and before Saturday was gone the panic may be said to have subsided; and credit, which had been suddenly prostrated by the irresistible force of the hurricane, albeit trembling and bewildered, stood erect once more.

From time to time, for two or three months past, there have appeared phenomena in the money market which were interpreted by some as prognostications of an approaching convulsion. They did not, it is true, show themselves in the usual order of succession. They were somewhat fitful in their occurrence, and rather indicated an abnormal state of things than pointed with consentaneous precision towards what was about to happen. The feel of the atmosphere, if we may be allowed the expression, created uneasiness occasionally amounting to anxiety. Still, general as may have been that undefinable sort of apprehension which so often foreruns a storm, nobody, it is probable, entered upon last week with the least idea of the proximity and irresistibleneas of the outburst he was destined to witness before its conclusion. No gloomy imagination prefigured anything which came near the actual event in destructive power. Its suddenness, its sweep, its terrific force, startled the stoutest hearted into dismay. Sensible men, men of cool reason and strong nerve, grew pallid at the prospect before them; for at midday, on Friday, it seemed as if the whole commercial and monetary system of the country would presently collapse.

The disturbed condition of the money market excited no terror until Thursday afternoon. It was then announced that the great discounting house of Overend, Gurney, and Oo. (Limited), had been compelled to suspend payment. The business, which was the largest of the kind in the City, and for the goodwill of which half a million sterling had been paid, had less than twelve months ago been transferred from the old firm to a limited liability company, who had since then reaped each an extent of loss sown for them by their predecessors, and had sustained such a singular concurrence of disasters, that speculative shareholders iu the concern took alarm and began to sell out. Shares naturally fell to a discount, and depositors, in turn, became nervous and apprehensive. A persistent and exhaustive drain of the resources of the establishment forced the managing directors to seek assistance from the Bank of England, which, stringently applying its own rule not to rediscount for discount houses, declined compliance with their solicitation. There was no time for employing any other expedient, and the company, with liabilities exceeding £10,000,000, of which £3,500,000 is covered by no security, had no option but to stop payment. The excitement caused by the announcement of this stupendous failure was intense, and the red sky of Thursday evening betokened a tempestuous morrow.

The morrow dawned upon three or four monetary disasters of appalling magnitude. The first sign of the distress, destined to increase hour by hour, was the raising of their rate of discount from 8 per cent to 9 per cent by the Bank of England. If such a bark, it was asked, is compelled to ride under storm sails, what is likely to be the fate of weaker craft? The reply, given by facts, came almost instantly. The English Joint-Stock Bank, with its thirty-one provincial branches, deemed it expedient to close its door for the present. This was but a comparatively small affair — a mere prelude of what was to follow. The next announcement was the stoppage of Messrs. Peto and Betts, the great contractors, whose liabilities were estimated at about £4,000,000. Two of the finance companies presently gave way — the Imperial Mercantile Credit Association, with a nominal capital of £5,000,000, and the Consolidated Discount Company, with a capital of £1,900,000. As information of the rapidly-extending ruin spread abroad, a complete panic seized the commercial world in London, Lombard-street was besieged by crowds of struggling and half-frantic creditors, and the heads of houses in Lombard-street fled for aid to the Bank of England. Upwards of £4,000,000 was distributed at 9, and in special cases at 10, per cent discount amongst the private and joint-stock banks and other establishments able to offer unexceptionable security ; and the Bank reserve, which in the morning stood at nearly six millions, was reduced to three before the close of business hours. The fury of the storm increased as the day wore on, and threatened to submerge everything exposed to its force. Solvent and insolvent firms were alike imperilled; and it became difficult, and in many instances impossible, to purchase safety at any sacrifice. The first mitigation of the prevailing terror was produced by an incorrect rumour that the Bank Charter Act had been suspended, on the responsibility of the Government. Then, even the despondent saw a break in the clouds, and the sun went down amid signs that the worst had already been enoowntered and that the next day might be a brighter one.

Fortunately, what was but an incorrect rumour at five o'clock on Friday afternoon had become before Saturday morning an indisputable fact; but the panic which was born of one fancy had been strangled by another. The Chancellor of the Exchequer stated in his place in the House of Commons at an early part of the sitting that there was no truth in the statement that her Majesty’s Government had authorised any step to be taken at variance with the provisions of the Act of 1844. At a much later hour, however, having in the interval reoeived a deputation from the joint-stock bankers of London, who corroborated the statements and enforced the request which Mr. Gladstone had previously received from the private bankers, he admitted that the state of things in the City and of the public feeling excited thereby called for the intervention of Government. Jointly with the First Lord of the Treasury, therefore, he had addressed to the Governor and Deputy Governor of the Bank of England a letter substantially the same as was addressed to those officers in 1847 and 1857. In other words, those potentates of the monetary world were recommended by the Queen’s Ministers, to the unspeakable relief of every banking and commercial establishment in the kingdom, if it should be found necessary to the restoration of confidence, to issue bank-notes beyond the limits fixed by law; and were promised, in case they should do so, a Ministerial application to Parliament for its sanction. It is not likely that any infraction of the statue will be needed, the mere liberty of the Bank of England to disregard its restrictive provisions having sufficed to dispel further apprehension.

In truth, the panic ceased almost as suddenly as it had sprung up. It was a single day of wild, ungovernable terror. Before the country could thoroughly realise the danger, it had passed. Men look back upon it and shudder at the thought of what it might have been, at what it must have been if the barriers of law had not been temporarily removed by the hands of the Executive. And, of course, retrospection is followed by discussion as to how the phenomenon may be best accounted for, and how a recurrence of it may be best avoided. Into such discussion we ore not about to drag our readers. Noting only as significant characteristics of the severest monetary crisis which has yet occurred that it was entirely limited to England, and that it happened at a time when, on the admission of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, there was no general unsoundness in the condition of our commercial relations, we content ourselves with sketching in barest outline the course of events, and with adding our voice to the universal utterance of thankfulness that the calamity is overpast, and that the ruin it caused was so much less extensive than was feared.

Bibliography

“The Panic in the City" Scene on Lombard-street on Friday.” Illustrated London News. 48 (19 May 1866): 477-878. Hathi Trust Digital Library version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 22 December 2015.

Victorian

Web

Economics

Archi-

tecture

London

London

Scenes

Next

Last modified 21 December 2015