First four photographs, and the last one, by the author. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Fifth and sixth photographs of the painted vault © Tim Crocker, architectural photographer, kindly supplied by the firm of Galliford Try, which was responsible for the recent restoration of the hotel. [Click on all images for larger pictures.]

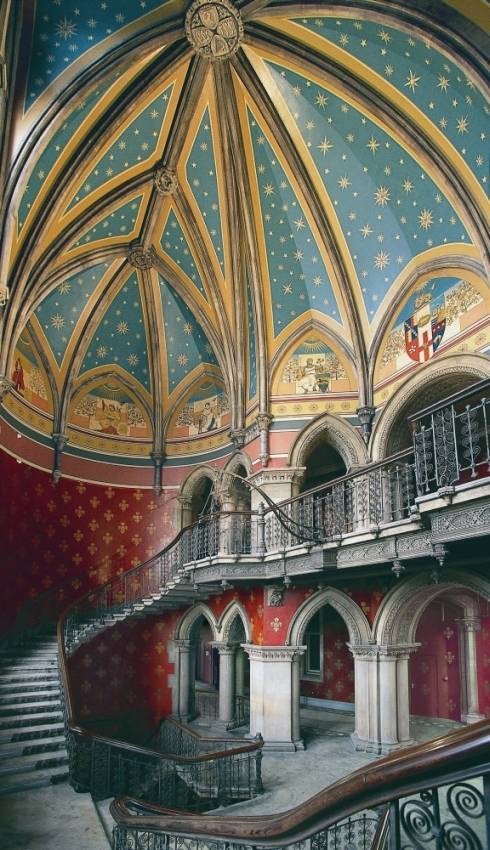

Left: The Grand Staircase in Sir George Gilbert Scott's former Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras, in north-west London, (1868-77), seen from the foot of the stairs. Right: Looking towards one side of the staircase.

Grand double or dividing staircases are a feature of many Victorian public buildings, such as town halls and museums. They can also be seen in clubs, stately homes and so forth. Impressive because of their size and complexity, they add greatly to the drama of the entrance and indicate the importance of the upper suites. That is certainly the case here, where the "curved-ended western wedge of the ground floor" was the only part of the St Pancras complex left for hotel use, forcing "some of its major rooms up on to the first floor" (Bradley 104). Alfred Waterhouse liked to make a play with views generated by his big stairways, excelling himself in the Gothic ones of the town hall and University Tower at Manchester. But everything the eye rests on there has a cathedral-like calm and dignity. What George Gilbert Scott has done here is quite different:

Architects had previously been at pains to hide any internal iron beams from the polite gaze, so the staircase shows Scott's courage twice over: as a structure (apparently designed without assistance from an engineer) and as a defiantly explicit expression of structural truth in one of the last places one would expect: a grand hotel. (Bradley 111)

The views of or from this staircase are not through beautiful streamlined shafts and pointed arches, like Waterhouse's. Rather, they consist of intriguing angles and turns, and rippling, concertina-like treads ascending on the brackets that project unexpectedly from the hotel walls. Scott had drawn attention to the ironwork of stairwells before, for example at the Leeds General Infirmary, but not to this extent. It really is an extraordinary expression of both his imagination and skills.

Left: The Grand Staircase, looking under the first landing, to where the stairs divide. Right: Looking right up through the stairwell at the painted dome.

Frederick Williams, historian of the midland Railway, was shown round the hotel before it was fully completed. He described his progress thus:

Turning through a door at our left, we find ourselves at the foot and in front of the grand staircase. It rises to the third floor, is lighted by three two-light windows which continue up to the roof, a height of 80 feet, and are divided by four transom windows; the whole being crowned by a groined ceiling, with stone ribs and carved bosses at the intersections, filled in with Portland concrete a foot thick, the face being finished with Parian cement, which some day will be coloured and decorated. The groined ribs spring from stone corbels, and are supported by green Irish polished marble columns. (347)

Too early to see the final effect, which would be given by the painted decoration, Williams focuses usefully on the architectural elements, and the natural lighting from the windows on the west elevation, giving on to Midland Road.

Left: Top of the staircase and dome. Right: Detail of the painting.

The richly stencilled walls of the main corridor and stairwell recreate the decorative scheme of 1901 (see Lansley 162, caption), but the top of the stairs retains the original 1870s decoration. Found before restoration to be in a "parlous state ... overpainted and crudely repaired" as well as damaged by water (Thorne 173), this decoration has now been fully restored. Below the spangling of stars in the cerulean roof are paintings of the virtues, with the arms of the Midland Railway over the rounded main arch. The designs of the figures were supplied by Edward William Godwin, and originally painted by Andrew Benjamin Donaldson, the painter who oversaw the work of Gillow and Co. (later Waring and Gillow) here, in 1876-77 (listing text). More numerous than the usual seven, they represent humility, liberality, industry, chastity, temperance, truth, charity, patience and industry (see Bradley 112). Simon Bradley describes them as "clear-lined and austere personifications" with "hints of a Japanese sensibility in the stylized suns and trees of the background," and explains that they were originally meant to grace the walls of the Earl of Limerick's castle at Dromore, an indication that the hotel was expected to be a venue for the upper and upper-middle classes (112-13).

The arms show a wyvern ("a sort of winged serpent ... the crest of the Mercian kings") above heraldic symbols of the major towns served by the company — a buck or deer representing Derby, a castle and ship representing Bristol, and other symbols representing Birmingham, Lincoln, Leeds and Leicester (Stretton 351). This sense of corporate and regional pride, the very pride that originally produced the Midland's grand terminus and splendid railway hotel at St Pancras, was lost with the nationalisation of the railways in the late 1940s.

Geometrically patterned and leaf-and-berry Minton tiling at the foot of the stairway.

Note: Stories Associated with the Grand Stairway

The Midland Grand took its first guests, before the whole hotel was completed, in 5 May 1873 (see Lansley 163). One of the early incidents there was a fatal fall over the first-floor banisters. It is not known whether the unfortunate Mr Stewart of Highleigh, Cheshire, was lost in admiration or despair, or had simply drunk too much. But the fact is that he died almost immediately (reported under the heading, "SAD ACCIDENT AT A HOTEL," in the Bury and Norwich Post, and Suffolk Herald of 13 October 1874, p.7). Sadly too, it was up these same unique stairs that the architect's grandchildren went on their last visit to their father, George Gilbert Scott Jnr. (1839-1897). The younger Scott's undoubted talent was vitiated by mental problems and a generally scandalous lifestyle, and he died while living in one of the suites here (see Bradley 10, and Stamp).

Related Material

- Exterior of Hotel, with Victorian and later commentaries

- Interior of the Hotel. Introduction and Entrance Hall

- Interior of the Hotel. Arches: A Gallery

- Interior of the Hotel. The Hotel Atrium

Sources

19c British Library Newspapers (Gale; via library portal). Web. 3 November 2012.

Bradley, Simon. St Pancras Station. Rev. and updated ed. London: Profile, 2011. Print.

Lansley, Alastair, et al.. The Transformation of St Pancras Station. London: Lawrence King, 2008. Print.

"St Pancras Station and Former Midland Grand Hotel, Camden." British Listed Buildings. Web. 3 November 2012.

Stamp, Gavin. "Scott, George Gilbert (1839-1897." Oxford Dictionary of Biography. Online ed. 3 November 2012.

Stretton, Clement Edwin. The History of the Midland Railway. London: Methuen, 1901. Internet Archive. Web. 3 November 2012.

Thorne, Robert. In St. Pancras Station, by Jack Simmons. Rev. and updated by Thorne. 2d ed. London: Historical Publications, 2003. Print.

Williams, Frederick Smeeton. The Midland Railway: Its Rise and Progress; A Narrative of Modern Enterprise. London: Strahan, 1876. Internet Archive. Web. 3 November 2012.

Last modified 5 November 2012