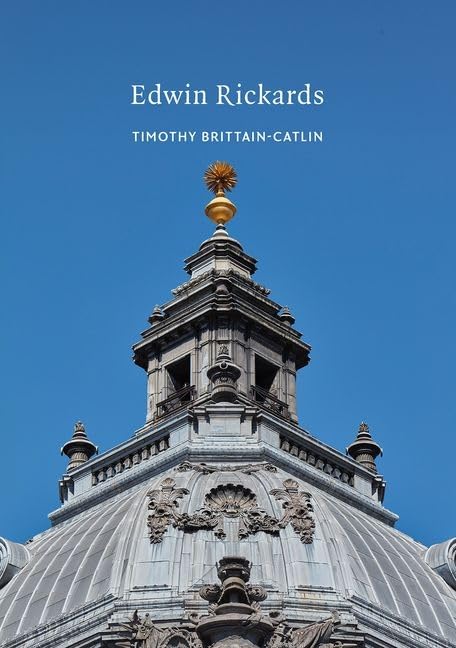

dwin Rickards by Timothy Brittain-Catlin is a beautiful book, a pleasure to look at and to hold. The illustration on the front cover shows the majestic dome of the Methodist Central Hall, topped by a sturdy balustraded cupola and crowned with a gilded explosion of a finial, soaring into the blue infinity of a cloudless sky. The irresistible urge to flick through the pages is rewarded by promising glimpses of colourful photographs, lively water-colours and the kind of pin-sharp sketches of people and architecture which will inspire many a reader to get a regrettably-neglected sketch-book out of the drawer, and - somehow - find the time….

But first, get to know this lively and talented young man, Edwin Rickards (and maybe discover how he found the time!) through the course of a career "which might properly be described as meteoric in that it sank as quickly as it had risen, waxing and shining before war and tuberculous meningitis put an end to it in 1920" (1).

Early Career

Aged 15, in 1887, Rickards became an articled architectural apprentice to R.J. Lovell, and an art student at the Royal Academy. We see a young man with a very clear idea of his own path to achievement - which was, however, not the way of the Royal Academy. Determined to pursue his own inclinations and imagination, rather than toil at the boring tasks set by his instructors at the Academy, he spent his time with a convivial bunch of sketching-friends, drawing objects and sculptures in the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) and St. Paul's Cathedral.

We follow Rickards' progress through election to the Architectural Association at the age of 18, where he studied and later lectured, to Fellowship of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1906. Taking advantage of the wide variety of work available to young architect-apprentices (who, while fully employed by one office, were prepared to free-lance for several others at the same time - as well as taking on work of their own!) he experienced the ambience of half a dozen different offices in the first two years of the 1890s. In Eedle & Myers he worked for a year on public house alterations in London, then spent a year with Dunn & Watson, and divided the next year, 1892, between Stokes, Howard Ince, George Sherrin and William Flockhart, before coming back for another year with Dunn and Watson.

The social side of life was equally hectic, including "unpublishable" (16) night-life activities in the theatrical world. He maintained a lasting friendship with the writer Arnold Bennett, who drew on Rickard's character and youthful experience for the young architect-hero, George Edwin Cannon, of the last of his "Clayhanger" books, The Roll-Call. This, however, was not a sustainable pace of life, and brought Rickards to the brink of a breakdown. Having made enough money to afford a well-earned, and very necessary, break in 1893, he took a three-month tour of Italy, France and Egypt.

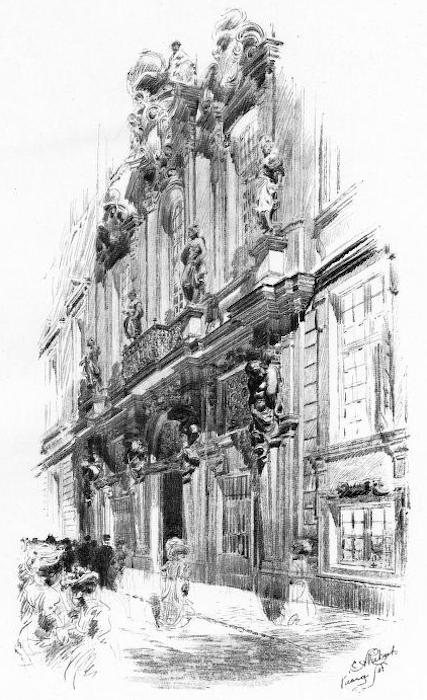

Rickards also travelled widely with Bennett, who rated him as an artist "of catholic tase … who was more than willing - it would be fairer to say eagerly anxious - to recognise merit in the productions of different styles and different ages" (17). It was, however, to the European Baroque, especially as experienced in Vienna, that he was specially drawn, "and he suffused his work in England with that spirit" (20).

Two of Rickards' sketches from his travels. Left: Fountains, Venice (Rickards 137). Right: Street in Vienna (Rickards 135).

Partnership with H. V. Lanchester

Rickards' senior colleague at Sherrin's was Henry Vaughan Lanchester. Nine years older than Rickards, Lanchester was well experienced in the efficient planning of large and complex buildings. His family background was in mechanical engineering, including major developments in the early automobile industry, and three of his brothers formed the Lanchester Engine Company in 1899. When he, James Stewart and Rickards became partners in 1893, Lanchester's maturity, experience and practical approach to design were essential counterweights to the ethereal products of Rickard's exuberant imagination, which Lanchester "had to tame, rationalise and build" (14).

Rickards' conception of the building structure was that of a necessary framework for the support of carvings, statues and elaborate detailing - "buildings should be created from the outset with plinths and niches for great sculptures as these become available" (20). The placing of these sculptures, or the accommodating spaces for them, was, of course, an essential part of Rickards' architectural composition of the facades of the buildings. The phrase "Must you have a window there?" became symbolic of the relationship between the partners (50).

Rickards' partnership with Lanchester and Stewart was formed primarily with a view to entering competitions. Chapter 3, "You never know your luck," gives a clear account of the perils and heartaches inherent in the competition system, which distributed commissions for most of the major buildings of the period. However, one major project was currently on hand in their office, a massive steel and concrete, red-brick-clad, factory for the Canadian Bovril company, in Old Street, Finsbury, London. In 1891, the Scottish chairman of the company, John Lawson Johnson, with whom Lanchester had a connection, had bought Kingswood House (built in 1811) in Seeley Street, London, and was having it remodelled in "Suburban Baronial" style, with rusticated stone cladding and castellated turrets, designed by Rickards.

The remodelled Kingswood House, c. 1916, when in use as a convalescent home (Darby 13).

Known as Bovril Castle, the house now stands surrounded by a relatively spacious and pleasantly landscaped post-war housing estate. Having served as a community centre, library, conference centre and wedding venue before some years of being closed, the building has recently been reopened by Kingswood Arts, as a Community Arts Centre.

In 1897, the original aim of winning competitions was triumphantly achieved by gaining the commission for Cardiff Town Hall and Law Courts. This was an opportunity, unique in England at the time, to design a complete municipal centre on a large open site, a concept imported from North America by a local architect and town councillor, Peter Price. Cathays Park had been owned by the Marquess of Bute, who also owned Cardiff Castle. The competition entries were assessed by Alfred Waterhouse (probably the busiest architect in the country) who checked through the 56 entries and announced the winners on the third day after submission. Lanchester and Rickards' two consistently detailed and perfectly balanced buildings stand in harmonious complement to each other.

Right: From a portrait of Rickards (1911), by Frank Waldo Murray. Source: Brandon 47. Left: Cardiff City Hall (click on the image for more information).

At a time when there was continual and confusing conflict between opposing views on the merits of so-called "correct" historical architectural style, Rickards cut through the rhetoric and declared that they were all wrong - "contemporary architects' mistake is their attempt at re-embodying the matter, rather than the spirit, of historic buildings" (25). Rickards believed that appropriate decoration was essential to make large public buildings comprehensible to the public, by both illustrating their purpose and relating the building to the human scale.

Inevitably, at a time of rapid technological and social change, imitation of past styles without fully respecting the underlying principles eventually triggers rejection. Within the first decade of the twentieth century, the pendulum of professional architectural focus had swung, from dependance on historically-based ornamentation, to the proclamation, by the Austrian architect Adolf Loos, that "Ornament is Crime." Rickard's entirely rational plea for the appropriate enhancement of bare structure was buried in the dust raised by the inexorable acceleration of the modernist movement.

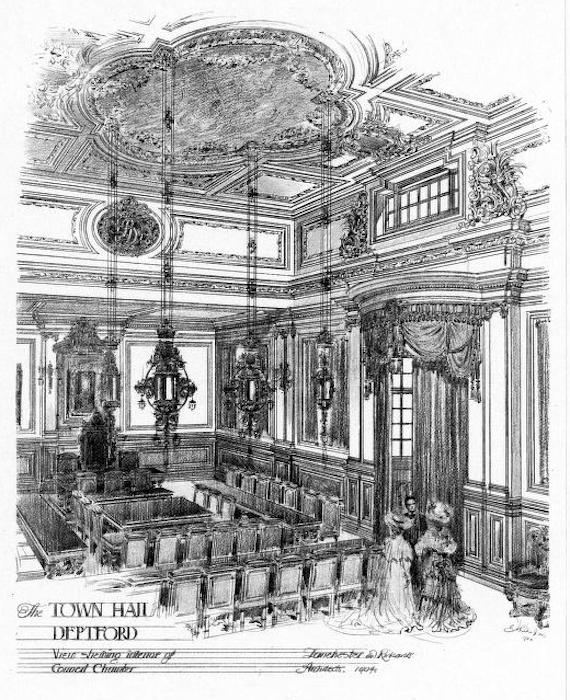

Right: Deptford Town Hall, London SE14, © Philip Talmage, posted on Geograph on the CC BY-SA 2.0 Deed (Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic) licence. Left: Architectural drawing of the interior of the Council Chamber, Deptford Town Hall (Rickards 43).

Rickards, however, continued to practice what he preached. The competition for Deptford Town Hall was won in 1902, beating 43 competitors. The design of the building drew on "the traditional style of seventeenth and eighteenth century buildings of the riverside towns such as Greenwich, Gravesend and Rochester" (61). The influence of two of Rochester's High Street buildings, the Guildhall of 1687 and the Corn Exchange of 1706, is readily detectable in the proportions of the windows and details of cornices, pediments, cupola and even a sailing-ship weathervane. As Brittain-Catlin says in his introduction, recent controversy surrounds the cultural background of the statues, which are an integral part of the fabric of the facade, with a campaign for their removal. The compromise reached, after public consultation, of adding explanatory text and additional compensating artwork, has yet to be fulfilled.

1902 was a highly successful year for the partnership, with a second competition win, for Hull School of Art. This is a red-brick jewel of a building, still in perfect original condition.

1904 brought the fourth, and last, of the partners' competition successes - the Methodist Central Hall in Westminster. Funded by the Wesleyan Methodist Twentieth Century Fund, which reached over a million pounds, this building embraced the latest forms of structure, reinforced concrete and steel. Opened in 1912, this magnificent building has hosted concerts and conferences, a Temperance talk by Mahatma Gandhi, the formation of the Free French Forces in the Second World War by General de Gaulle, the Inaugural Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly, Billy Graham, Nikita Kruschev, the launch of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Dr Martin Luther King and the first performance of Joseph and his Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat. A full programme of conferences, concerts and church services continues to keep Rickards' achievement in the forefront of the cultural life of the capital city.

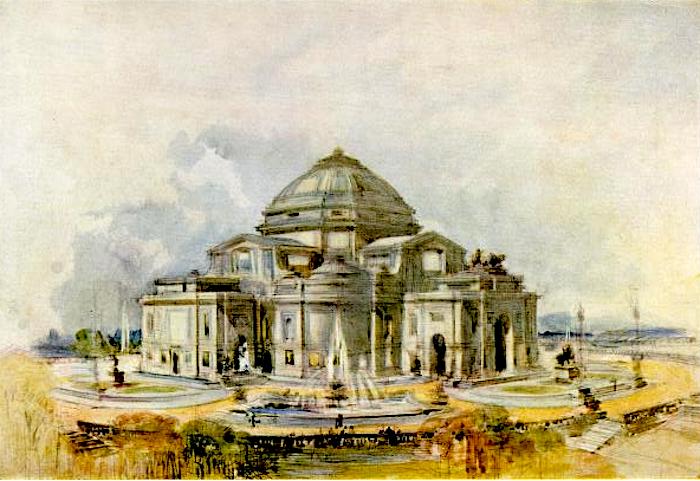

Rickards' career included many designs for war memorials, monuments, and a rather splendid horse-trough, known as the Cooper Memorial Fountain, in Newmarket. His final project was the Canadian Imperial Memorial for Ottawa, but by 1919 Rickards' health was failing. The project lost momentum and was never realised. In May 1920 Rickards was taken to the Home Sanatorium near Bournemouth, where he was still talking inexhaustibly, designing, drawing and painting watercolours until he died on 28 August.

Left: Methodist Central Hall, Westminster (click on the image for more information). Right: Design for the Canadian War Memorial that was never built (Rickards, frontispiece).

If we think the pace of life has increased during the course of the last century, this vivid and thought-provoking account of the variety, concentration and competitiveness of architectural activity 120 years ago must give us pause for thought. Getting to grips with new techniques, new materials and new social requirements, while respecting the value of the traditions and legacy of the past, is not just a recently formed maze for today's aspiring - and practicing - architects to navigate. One small quibble: for such readers, the illustrations, splendid as they are, could sometimes have been better placed. For example, the Introduction starts by making a dramatic feature of the controversy surrounding the statues adorning Deptford Town Hall. However, the full-page colour illustration on the facing page is that of Cardiff City Hall: Deptford Town Hall is illustrated much later. A page reference here would have helped. On another occasion, a description of the layout and staircase arrangement in Cardiff City Hall would have benefitted greatly from an illustration of the plan. Both general and professional readers will, nevertheless, find much to inspire them in Timothy Brittain-Catlin's handsome and most enjoyable Edwin Rickards.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Brittain-Catlin, Timothy. Edwin Rickards. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press / Historic England, 2023. pbk. 168 pp. ISBN 9781837645077 £30.00.

[Illustration source] Darby, Patrick. A History of Kingswood House, Dulwich. London: Southwark Local History Library, 2010. Open source. Internet Archive. Web. 26 January 2024.

[Illustration source] Rickards, E.A. The Art of E. A. Rickards. London: Technical Journals, 1920. 1-6. Internet Archive. Web. 26 January 2023.

Created 26 January 2024