Photographs by the author, and scanned image added from the Wellcome Library, London, on this Creative Commons Licence by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also supplied some extra details from the sources listed in the bibliography. Special thanks to Ash Nallawalla for pointing out earlier confusion on this page between this and the later college building. You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print document. Click on all the images to enlarge them.

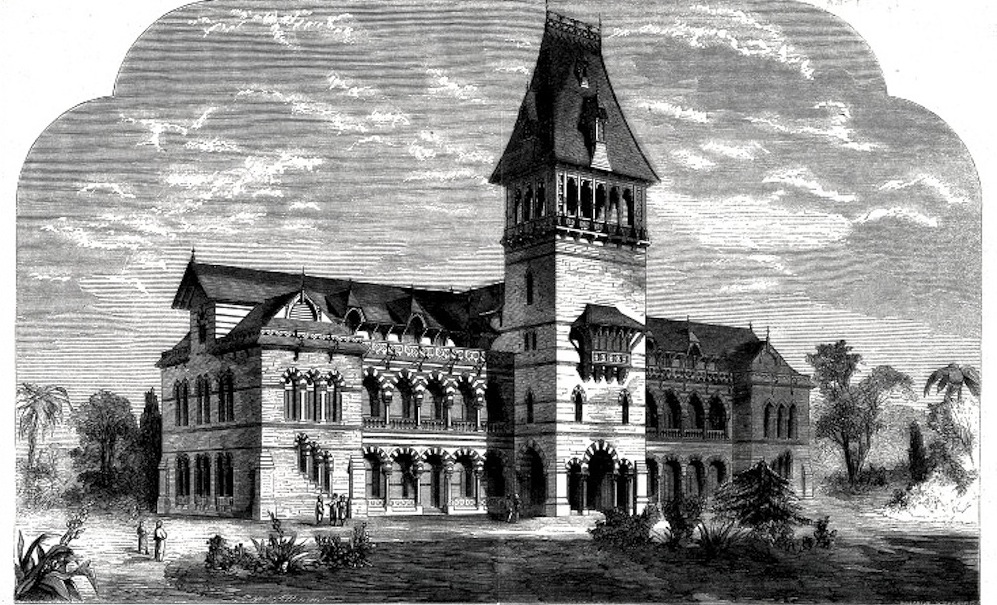

Wood engraving by Gascoine and Maguire, 1866, after James Trubshawe, published in The Builder, 3 November 1866, p. 815. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London.

(Former) Elphinstone College, by James Trubshawe, an architect who flourished between 1860-75, and was well known in India for his Gothic Revival buildings — although this one perhaps is better described as "Bombay Gothic" or even "Romanesque transitional" (see "Elphinstone College"). It was completed by the Public Works Department's engineer and architect John Adams (1845-1920), and opened in 1871. The building stands opposite the Victoria Memorial Gardens in Byculla, Mumbai.

The college was planned in the 1860s as one of the first great institutions of the Victorian age in Mumbai. The phasing out of the East India Company and the introduction of Victorian-age civic institutions and municipal governance in 1858 was a positive phase in the development of the city’s public administration and infrastructure. The decadent constraining factors like the old Bombay Fort of the EIC were removed and the city could now extend right into Byculla, and later Parel. This institution for scholarly excellence was constructed right opposite the Victoria Gardens, now called Rani Bagh after a change of names, where the Victoria and Albert Musueum (now Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum) was sited. While the institution is of the Victorian age, it honours Lord Elphinstone (1779-1859), who was the Governor of Bombay from 1819 to 1827, and who significantly contributed to the development of the city in those earlier years.

Left: The bell-tower, with its elaborately carved gallery. Right: Close-up of the gallery.

Sir Bartle Frere, the visionary governor who wanted to create the new city layout based on the modern needs of a great commercial city, laid the foundation of the new college. It was a true east-west collaboration. Sir Cowasjee Jehangir, in his eternal grandiosity, paid for the building. The architect George Twigge Molecey, and his business partner and draughtsman Walter Paris, who had come out to Bombay with Bartle Frere's encouragement in 1865, provided the working designs: drawing up Trubshawe’s Bombay projects was their first assignment (see London 140-41). Indian sculptors on the site used Lockwood Kipling’s sculptural style for the foliated details: Lockwood Kipling, 1837-1911, was Rudyard Kipling's father; he was then director of the School of Art in Bombay, and contributed much through his students to the sculptural ornamentation of the city (see Morris 133). Muccoond Ramchander supervised the carvings; his style and commitment got him several government assignments on public buildings including St. Thomas's Cathedral.

The tower is high and dominates the skyline for miles even now. Its balconies of wood and stone were enlarged to make them distinctive external features, more reminiscent of "the ornately carved galleried fa&ccedi;ades of local Gujurati houses" than Venetian Gothic (Davies 167). The woodwork is very elaborate and delicately done. Corrugated iron was used for the roof, which was a new architectural introduction. The college had a multi-purpose basement, four lecture halls on the ground floor, two large rooms and a small one on the first floor, and a fifty-bed dormitory on the third floor. The cast iron railings came from England.

The college's premises were soon moved, and the building now houses a railway hospital, which has built a large main building around the structure. According to Philip Davies, it has "suffered from unsympathetic infilling of the first-floor arcade and painting of the stonework" (167). This kind of development is inevitable in view of today’s needs for space and infrastructure. However it is good that the original building is still preserved and has not been razed, like the other Gothic-style heritage buildings at JJ (Sir Jamshedjee Jeejeebhoy) Hospital nearby. We hope it stays that way.

Related Material

Sources

Davies, Philip. Spledours of the Raj: British Architecture in India, 1660-1947:. London: Penguin, 1987.

"Elphinstone College, Bombay." British Library Online. Web. 29 May 2016.

London, Christopher W. Bombay Gothic. Mumbai: India Book House, 2002.

Morris, Jan.Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Tindall, Gillian. City of Gold: The City of Bombay. New Delhi: Penguin, 1992.

Updated 7 October 2020