Pencil and watercolour cartoons and plaster maquettes, photographed by Tomás Tyner, reproduced here by kind permission of the Lewis Glucksman Gallery, Cork. Copyright remains with the gallery. Other photographs of the cathedral by the author. You may use the latter (only) without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) either link your document to this URL or cite it in a print document. Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

Detail (upper half) of the cartoon for The Creation of the Eve, in the west wheel window. Source: Glucksman 20.

The front cover of this book bears the title Searching for the New Jerusalem: The Iconography of William Burges, but the title page itself puts the focus, more manageably, on the iconography of Burges's St Fin Barre's Cathedral. The Very Revd Nigel Dunne, and Michael Murphy, Dean of Cork and President of University College Cork, explain in the Foreword that the cartoons for the cathedral's stained glass windows and mosaics, and the maquettes for its sculptures, were not, as was once thought, destroyed on the building's completion. They were found by Dr David Lawrence in the 1990s. Since then, the maquettes have been stored in the cathedral's north tower, where they were photographed for the new edition of Joseph Mordaunt Crook's book on Burges (167); and most of the other artefacts have been kept in the Boole Library of the University of Cork. A public showing of them from November 2013 to April 2014 at the Lewis Glucksman Gallery in Cork was, therefore, a major event for Burges scholars. This slim book, which originally served as the exhibition catalogue, now allows those of us who missed it to enjoy the beautiful and moving iconographic scheme that it revealed.

William Burges as "Art-Architect"

St Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork, Irish Republic, 1865-79, though the carving on the west front would not be completed until 1883.

St Fin Barre's was Burges's first big commission — a cathedral, a building that would be a monument to God and to his own life's work. He poured his heart into it, taking a thoroughly hands-on approach to every aspect of the building and its decoration, which, like A. W. N. Pugin, he saw as quite inseparable. In the essay that constitutes the text of the book, Richard Wood tells us that Burges designed all the stained glass windows, mosaics and sculptures himself — an astonishing feat, considering the sheer scale of the project: there were 1,260 pieces of architectural sculpture and seventy-four stained glass windows (Crook 167, 172). These designs were executed for the architect by his small, trusted team of artists: principally Horatio Lonsdale (1844-1919), who produced most of the working cartoons in pencil and watercolour for the stained glass manufacturers, and Thomas Nicholls (c.1825-1900), who executed the maquettes for the stonecarvers. Even the stainer-glazier was "under the immediate superintendance of the architect" (qtd. in Crook 172), and the local stonecarvers entrusted with the architectural carving were hand-picked too. In this way Burges could ensure that every detail of his vision for the cathedral was fully realized.

The West Front

Left to right: (a) The Bridegroom between the west doors. (b) The Angel with an open book in the apex. (c) The plaster maquette for the figure of Christ which was intended for the apex, but never executed (source: Glucksman 53). The open book would still be featured.

Or almost fully realised. Burges had been successful in winning approval for a project far above budget. But he could not circumvent what Wood calls the "scruple of mid-nineteenth century Protestantism" (10) in Ireland. This prevented him from representing Christ and other figures of worship directly. He would like, for instance, to have put the figure of Christ as Divine King and Judge between the two central doors of the west front. Wood explains that this would have led up to the reliefs on the tympani above, which feature Solomon (as King) and Adam and Eve being banished from Paradise (as a Judgement). Instead, he had to put there the "simple Jewish bridegroom, who, in the parable of the virgins [seen either side of the whole portal] represents the second coming of Christ" (Wood 10). Similarly, Burges would have liked to place, and did indeed design, the figure of Christ in Glory on the gable here. The maquette was made: it is shown in the last section of the book. But an angel had to do service for it, though Wood tells us that Burges managed to get "the hand that blesses the world" past his censors by placing it unobtrusively "at the apex of the arch of the central portal, hidden underneath" (10).

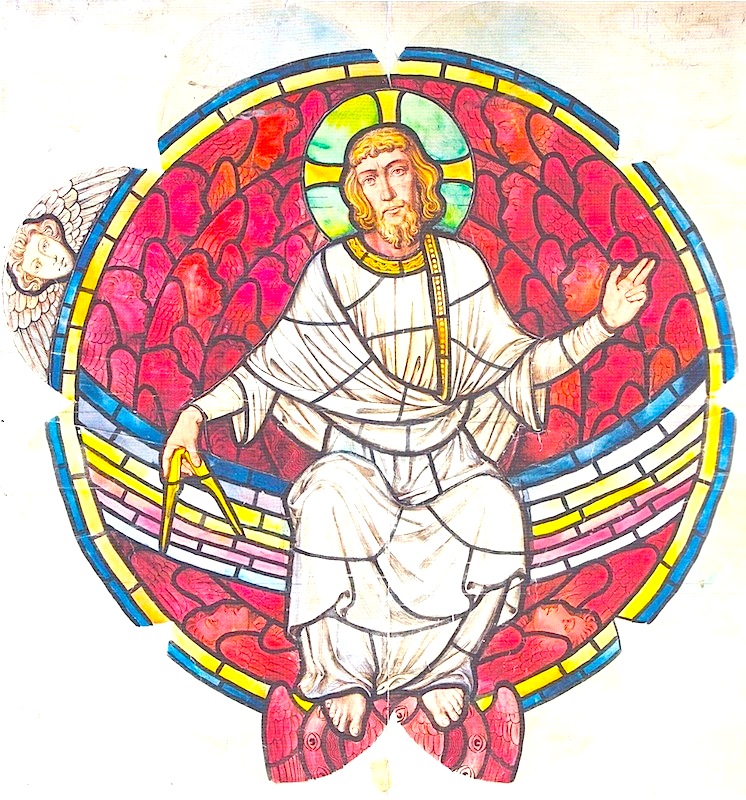

Left: The west window exterior, with representations of the four Evangelists at each corner. Right: Pencil and watercolour cartoon for Christ in Glory at the centre of the window. Source: Glucksman. Note that Christ is also seen as Creator here, with a pair of compasses in hand.

Despite such constraints, Burges was able to produce a remarkably coherent and harmonious iconographic scheme. This starts, even if not as completely as hoped, on the exterior of the west front. Here, the great wheel window is enclosed by a square, in each corner of which is a representation of one of the four Evangelists: Matthew as a man, top left; Mark as a lion, bottom left; Luke as an ox, bottom right; and John as an eagle, top right. These, says Wood "announce the Cathedral's purpose" (9). In the stained glass at the centre of the wheel window itself, seen from within the nave, Christ appears at last, seated on a rainbow and surrounded by the angelic host, with the days of creation gloriously depicted in the outer circles. The cartoons for these are perhaps the most gorgeous of all those shown here, no doubt benefitting from the conservation work that is still in progress. They glow on the page almost as much as they do when illuminated by shafts of sunlight within the cathedral.

The Creation

Detail (upper half) of the cartoon for The Creation of the Birds and Fishes, with peacock in pride of place, but also a vulture with its bald head (right), a parrot (Burges's favourite), a hoopoe with its fan-shaped crest, a heron standing in the water, and one or two more homely birds as well. Source: Glucksman 18.

Better still, on the page every detail is visible: trees, bushes and plants with a variety of leaves and fruit for the "Creation of Dry Land"; sun and moon with faces in the "Creation of the Sun, Moon and Stars"; the individual feathers of the attendant angel's wings in "The Creation of Eve," and so on. In others ("The Creation of the Birds and Fishes," "Adam in the Garden of Eden," and "Adam Names the Animals") Burges's humour was irrepressible. He has had great fun with the creatures of the earth, showing a pelican in the act of swallowing a fish, a squirrel with an acorn, a tortoise rather comically paired with a greyhound, a monkey holding an apple, and so on. His fertile imagination, the same faculty that would produce the teeming, ebullient and quirky decorations of his secular works, is evident here. Wood usefully explains another part of the effect: the medieval two-dimensional technique and colour variations that Burges, like other Gothic Revival artists, adopted and capitalised on, produced simultaneously bold and shimmering lights.

The Nave and Transepts

Left to right: (a) A nave window showing Cain and Abel Sacrificing. (b) Cartoon for Abraham and the Three Angels. Source: Glucksman 24. (c) Cartoon for Daniel in the Lion's Den, with King Darius, tired after his sleepless night, peering in at the unscathed victim with a mixture of relief and awe. Source: Glucksman 34.

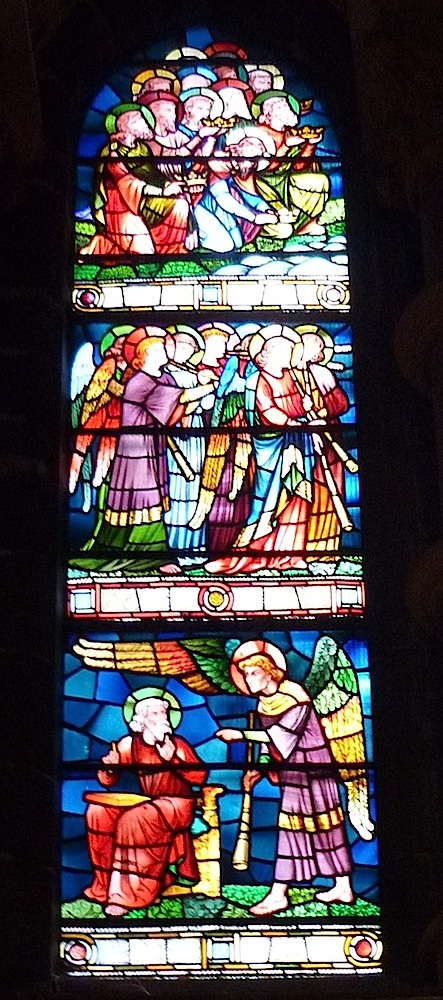

The lancets of the nave then depict episodes from the Old Testament that foretell those in the New Testament, the sequence moving back and forth across the nave from the north west to the south east. The exhibition showed some of the cartoons for those along the north wall, as others have yet to be conserved. But these are enough to demonstrate the pattern: as seen in the photograph above left, these windows feature white-robed figures in the central panels, against backgrounds of either red or blue, with grisaille and geometric patterning above and below (light being an important consideration for the nave). The individual episodes have different spiritual imports, Cain and Abel's story, for example, issuing a warning, while Abraham's welcoming of the three angels encourages us to be open and receptive to the word of God. Then come the transepts, with their taller lancets depicting the prophets who foretold the coming of Jesus, their lives related in four lights each, reading from bottom to top. The figures wear coloured robes, and are shown against white backgrounds. Here, the exhibition could show Zechariah from the north transept, and Daniel from the south. The former appears on the cover of the book, shown at the end of this review: an angel is holding out the measuring line for Jerusalem, and the prophet receives the marvellous news that one day Jerusalem will be a great city that will need no walls, "For I, saith the Lord, will be unto her a wall of fire round about, and will be the glory in the midst of her" (Zechariah 2,v). This is the hope with which the whole scheme is imbued.

The Sanctuary

Left to right: (a) Cartoon for the Resurrection of Christ, worked up by Frederick Weekes. Source: Glucksman 44. (b) One of the windows illustrating Revelations, showing St John with the angel at the bottom, angels sounding their trumpets in the middle, and the elders at the top, casting down their crowns. (c) Cartoon for the mosaic Piscator (Fisherman). Source: Glucksman 49. (d) Cartoon for the Lobster mosaic. Source: Glucksman 51.

In the sanctuary, the focus moves to the events of the New Testament, the climax coming high up in the clerestory window. Since current Anglican thinking prevented Burges from showing a true crucifixion scene lower down — he shows there instead the descent from the cross — he presents the resurrected Christ in the clerestory instead, "against His cross, alive and robed as a royal figure, triumphant over death" (Wood 12). Here is the fulfilment of the various prophesies and signs, and so, in a large part, here too is the culmination of the cathedral's iconography. The cartooning of the three most important windows here was entrusted to Frederick Weekes (1833-1920). Finally come some scenes from Revelations, in which figures wearing coloured robes are set against a rich blue backdrop.

But Wood points out helpfully that another element finds its fulfilment in the sanctuary as well. Humanity, represented on the west front by the wise and foolish virgins, has found its way here too, and is pictured in the mosaics of the sanctuary floor. Here we see "all manner of mankind, caught in the net of redemption along with the fish" (Wood 13). Thus, cartoons for a country workman and a fisherman are shown in the catalogue, the former about to take his axe to a small tree trunk, the latter gathering up his lively catch. A wonderfully colourful fish and precisely realised lobster complete this group of illustrations in the book.

The Maquettes

Left: Three of the foolish virgins by the doors of the west front. Right: Plaster maquette for the virgin on the left. Source: Glucksman 57.

Last but not least, the catalogue features a few of the plaster maquettes, the first amongst them being that never-to-be-executed Christ enthroned in Glory for the west front. Then come Adam and Eve Expelled from the Garden of Eden and King Solomon Dedicating his Temple for the tympanum above, and an example each of the wise and foolish virgins at the portal. Burges has caught the disappointment of the latter perfectly, in both her expression and her body language, as she shrinks into herself at the prospect of, or in the knowledge of, rejection.

This beautifully produced and illustrated book will appeal to everyone, not just to those with a special interest in Burges and/or St Fin Barre's, for whom it is absolutely essential reading. It does need to be read alongside Crook's magnificent William Burges and the High Victorian Dream, which gives so many more details about the processes and craftsmen involved, but then the focus here is on the iconography, and Wood's essay on that makes a properly illuminating introduction to the stunning full-page illustrations that follow. There is a tiny typo on the back cover ("relevation" for "revelation") just to prove that we are all, indeed, human!

Cover of the book under review, showing the cartoon captioned Zechariah measuring Jerusalem for one of the lancets of the north transept.

Related Material

- Another of the Revelations windows, dedicated to the memory of the architect

- The tympanum of Burges's All Saint's, Fleet, Hampshire (Christ in Glory, hand raised in blessing, far right in the first row of images)

- Benedicte windows by Edward Arthur Fellowes Prynne (see the last two, illustrating angels with fish and fowl)

References

Book under review: Searching for the New Jerusalem: The Iconography of St Fin Barre's Cathedral, with a Foreword by the Very Revd Nigel Dunne, Deane of Corke, and Michael Murphy, President, University College Cork, and "Searching for the New Jerusalem," an essay by Richard Wood. Cork: Lewis Glucksman Gallery and the University of Cork, 2013. 60 pp. ISBN 978-1-906642-68-6. €15.00. Website: http://www.glucksman.org.

Crook, J. Mordaunt . William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. Revised and Enlarged Edition. London: Francis Lincoln, 2013.

Last modified 10 April 2014