The abbreviations A and MN in the in-text citations refer to Armadale and The Meaning of Night respectively.

Introduction

ypical in many ways of the mid-Victorian sensation genre, Wilkie Collins's Armadale (1866) starts with rival heirs to a great estate, peers into the subconscious through a complex dream sequence, involves drugs, poison and poisonous fumes, and explores the seamy city backstreets where even buildings can look "furtive" (A 408). Much more recently, Michael Cox employs similar elements in his sophisticated neo-Victorian thriller The Meaning of Night: A Confession (2006). He also includes scholarly apparatus provided by a fictitious editor called J. J. Antrobus, designated on the title page, "Professor of Post-Authentic Victorian Fiction, University of Cambridge." Cox's earliest successes were in the rock music world, so this might be a teasing reference to the Canadian rock group of that name. But it also serves to remind us of Collins, who started his working life as an apprentice to Antrobus & Co., tea merchants in the Strand (see Pykett 6-7). Supporting the idea of a link to Collins on the title page, Cox mentions Collins in the book itself (MN 125), and also refers to the earlier novelist in an interview, listing among his favourite Collins novels The Woman in White (1860), Armadale (1866) and The Moonstone (1868). The techniques and preoccupations with which Cox juggles can be found in all three, along with a "surprisingly modern view of fiction as artifice or construct" that must have appealed to him (Lonoff 108). Echoes abound: in The Moonstone, for example, John Herncastle, who first steals the sacred gem, is variously reported as having turned to opium, antiquarian book-collecting, and "carousing and amusing himself among the lowest people in the lowest slums of London" (31) — all pastimes in which the central character of The Meaning of Night also indulges. But Armadale, with its focus on how one of two male protagonists feels about the other, perhaps inspired the later novel most.

ypical in many ways of the mid-Victorian sensation genre, Wilkie Collins's Armadale (1866) starts with rival heirs to a great estate, peers into the subconscious through a complex dream sequence, involves drugs, poison and poisonous fumes, and explores the seamy city backstreets where even buildings can look "furtive" (A 408). Much more recently, Michael Cox employs similar elements in his sophisticated neo-Victorian thriller The Meaning of Night: A Confession (2006). He also includes scholarly apparatus provided by a fictitious editor called J. J. Antrobus, designated on the title page, "Professor of Post-Authentic Victorian Fiction, University of Cambridge." Cox's earliest successes were in the rock music world, so this might be a teasing reference to the Canadian rock group of that name. But it also serves to remind us of Collins, who started his working life as an apprentice to Antrobus & Co., tea merchants in the Strand (see Pykett 6-7). Supporting the idea of a link to Collins on the title page, Cox mentions Collins in the book itself (MN 125), and also refers to the earlier novelist in an interview, listing among his favourite Collins novels The Woman in White (1860), Armadale (1866) and The Moonstone (1868). The techniques and preoccupations with which Cox juggles can be found in all three, along with a "surprisingly modern view of fiction as artifice or construct" that must have appealed to him (Lonoff 108). Echoes abound: in The Moonstone, for example, John Herncastle, who first steals the sacred gem, is variously reported as having turned to opium, antiquarian book-collecting, and "carousing and amusing himself among the lowest people in the lowest slums of London" (31) — all pastimes in which the central character of The Meaning of Night also indulges. But Armadale, with its focus on how one of two male protagonists feels about the other, perhaps inspired the later novel most.

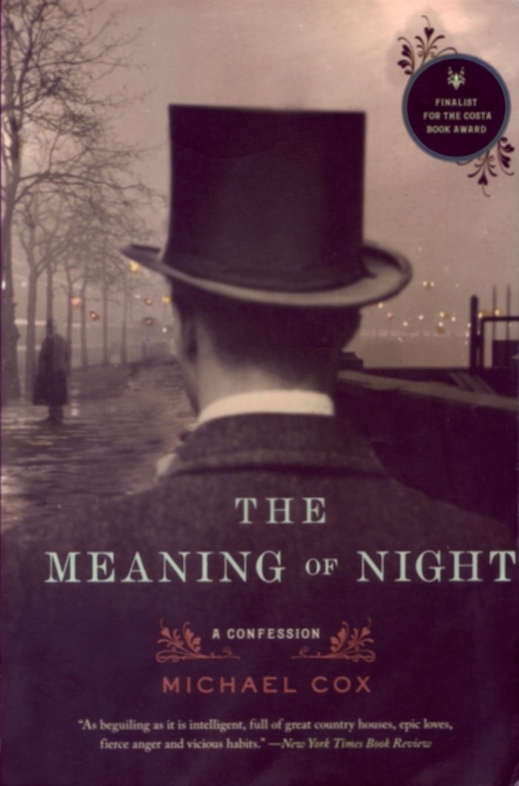

Left: Front cover of The Meaning of Night (2006): "He is there, though I cannot see him now — he seems to melt away into the darkness, to become a shadow" (MN 495). By permission of W. W. Norton & Co. Right: Aubrey Beardsley's black cat, from his illustration for Poe's famous tale of that title. Beardsley's one-eyed cat seems to wink at us. Source: Poe's Tales (1901), at the Library of Congress Digital Gallery, repro. no. LC-USZC2-3781. [Click on the thumbnails for larger pictures.]

That one of these works is indeed "surprisingly modern," and the other surprising in its Victorianism, is to the credit of both, and helps explain their popularity. The serialisation of Armadale revived the fortunes of Harper's New Monthly Magazine when it first appeared in serial form (see Davis 246), while The Meaning of Night was a finalist for the Costa Book Award of 2006. Yet each, at core, is very much of its own age. Behind and irradiating the melodramatic props of Collins's "authentic" work is a compelling moral and spiritual vision. By foregrounding a homosocial attachment, this author shows compassion where least expected, for his mixed-race protagonist Midwinter. Through his "terrific villain" Miss Gwilt (Eliot 465), who gave her name to the stage production of the novel (see Gasson 11), he also demonstrates a sensitive understanding of women's disadvantages and struggles in the mid-Victorian period. More fundamentally, in this, his longest novel, Collins explores the competing claims of Fate, Chance and Providence to influence human life — a debate from which emerges a typically Victorian faith, profound if embattled, in the redemptive power of love. Cox, on the other hand, operates with a sly and constant humour. In the first sentence of his "confession," the main protagonist and narrator Edward Glyver calmly reports having murdered a red-haired man before dining on oysters. Absolving himself from personal responsibility, this anti-hero is "a fervent believer in Fate" MN 525), who always sees himself in "the Iron Master's hand " (MN 125). When he is left at the end with "a one-eyed cat, of superlative hideousness" MN 694), straight out of Poe, as his sole companion, this seems to confirm that everything here can be read as an elaborate joke on the reader.

An 1864 advertisement for Armadale in The Reader along with one for a novel my Eliza Lynn Linton. Click on image to enlarge it.

Not the least of Cox's witticisms lies in the role played by books themselves in the novel. Edward's mother, or at least the woman he knew as mother, was a writer, always hunched desperately over her desk, while he and several other characters are bibliophiles with an obsessive interest in antiquarian books. Intertextuality is as great a sport throughout as metafictional layering. When reviewing The Meaning of Night for The Guardian), Giles Foden suggested that Cox was labouring under the "anxiety of influence," but surely he is playing with rather than groaning under his authentic models here. His novel, like its sequel The Glass of Time (2008) is clearly a clever postmodern production. But is it anything more? Perhaps not. Looking at Armadale and The Meaning of Night shows what William James termed "the feeling heart" (190) in the former, making Cox's use of the term "post-authentic" on his title page seem only too well justified.

- Part I ("Inheritance Issues" and "Friends and Foes")

- Part II ("Complications and "Contrivances")

- Part III ("Narrative Strategies" and "The Feeling Heart")

- Part IV ("The All-Merciful" and Conclusion)

Related Material

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. Armadale. 1866. Ed. Catherine Peters. Oxford: Oxford University Press (Oxford World's Classics), reissued 2008.

_____. The Moonstone. 1868. New York: Knopf (Everyman's Library), 1992.

Cox, Michael. The Meaning of Night: A Confession. New York & London: Norton, 2006.

Davis, Nuel Pharr. The Life of Wilkie Collins. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1956.

Eliot, T. S. "Wilkie Collins and Dickens" (1927). Selected Essays. 3rd ed. London: Faber, 1951. 460-70.

Foden, Giles. "Vivat Victoriana" Review of The Meaning of Night: A Confession. The Guardian, 23 September 2006. Web. 26 Nov. 2011.

Gasson, Andrew. Wilkie Collins: An Illustrated Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New ed. London: Penguin Classics, 1983.

Lonoff, Sue. Wilkie Collins and His Victorian Readers: A Study in the Rhetoric of Authorship. New York: AMS Press, 1982.

Pykett, Lyn. Wilkie Collins. Oxford (World's Classics paperback): Oxford University Press, 2005.

Created 26 November 2011

Last modified 25 July 2016