ROBABLY the title is one that

challenges the question,

“ Was not Blake his own?”

No one who knows anything

about that extraordinary

poet-artist and mystic — the

man of whom Swinburne

has written that “he was

made up of mist and fire,

the main part of him inexplicable, working out of all

rule and yet by law, having

a devil whose name was

Faith, and believing in

spiritualities as a materialist

believes in bread and meat”

— but is familiar with the

history of the inception and

production of those unique works, The Songs of Innocence and

"The Angel." From The Songs of Experience. By permission of Mr. David Nutt.

Of the songs themselves it is not our province here to speak. Nothing like them exists in our literature, either as regards the glimpses of divine melody and ancient simplicity, the “perennial freshness and bloom as of a growing violet,” the rainbow sparkle of child¬ hood’s visions, and the heavenly temper of The Songs of Innocence; or the darker phases of feeling, profounder meanings, and ruder eloquence of The Songs of Experience.

Of Blake’s own drawings for his poems, his biographer has well said that “in composition, colour, pervading feeling, they are lyrical to the eye, as the songs to the ear.” Of the two books, the drawings for Innocence are finer and more pertinent than those for The Songs of Experience. But, while not unmindful that Blake himself thought his poems finer than his designs, it cannot be stated here too frankly or too emphatically that work from no other hand will ever either equal, supplant, or supersede those wonderful decorations and pictures made by the poet for his poems, and nothing could be farther from the mind of the lady whose drawings accompany this article, than to attempt anything so foolish and so presumptuous.

While the Songs themselves have been reprinted until they are pretty widely known, such a course has been obviously impossible in the case of the coloured pictorial pages, or plates, by means of which Blake first gave them to the world. When these literally "home-made" books were first produced, they met with but scant appreciation, and were indeed only disposed of with much difficulty, through the indefatigable exertions of Linnell, to friends who hardly wanted them, and considered it almost giving away the money. Now very few of them are extant, and where they exist they are either in the National Collections, or are the jealously guarded possessions of wealthy bibliophiles.[237/38]

[Celia Leveton] Photo by Harold Baker, Birmingham.

Seeing, therefore, that Blake’s own designs can never be widely known and disseminated, I trust that no apology is needed for a young artist who, having never seen Blake’s designs, and influenced only by the spirit of the master as it breathes in his poems, has put forth a series of illustrations for a popular edition of the Songs; which, wuthout the faintest idea of emulation of, or comparison with, Blake, are an honest, individual, and interesting essay in his spirit and under his inspiration.

Celia Levetus, whose portrait decorates these pages, is an illustrator who has already achieved something; but no secret need be made of the fact that, though an illustrator of experience, her best work remains, I hope, yet to be done, and in no sense is finality possible in any consideration of her work at the present time.

The art of Miss Levetus has an additional interest, however, from the fact that it is a product and outcome of that School of Book Decorators that has its home at the Birmingham Municipal School of Art. As a beginner and student she was trained in the methods and nurtured upon the principles that have become famous as those of the Birmingham School, so emphatically endorsed by the late William Morris. Quite apart from the particular principles of book decoration with which Birmingham is identified, the ability with which the Municipal School is conducted, and its unique position as an art-centre, are too well knowm to need comment here. It was early recognised that Celia Levetus was a pupil possessed of a fine decorative sense, of remarkable facility of composition, and of imagination that never ran dry. Her latent impulses were studied and were allowed to develop in a natural, unforced way, the master to whom she feels more immediately indebted for help and guidance being Mr. Gaskin. In due course the usual certificates were gained for geometry, light and shade models, freehand, and finally a South Kensington Scholarship.

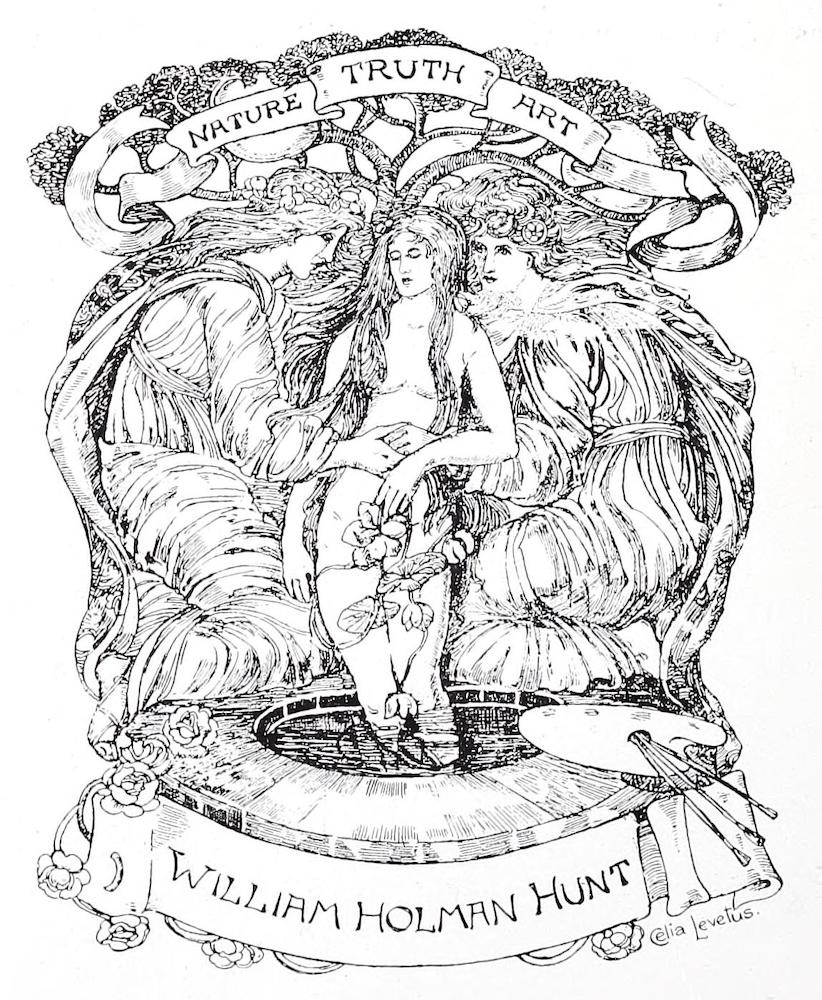

Two bookplates by Celia Leveton. Letf: By permission of Mr Howard Baker. Right: By permisson of Holman Hunt, Esq.

In a school such as that presided over by Mr. Taylor, a reasonable latitude maybe expected to be allowed to a promising pupil, and as a matter of fact Celia Levetus may be said to have practically managed her own career at the school, studying what she felt most need of, and dodging what she did not want. Besides the book decoration, she has also paid attention to Limoges enamel, decorative needlework, stained-glass designing, modelling, and painting.

From the first the lady’s career has been a smooth one. Encouraged by her masters in the school, and by artists outside, like G. F. Watts, R.A., Walter Crane, Holman Hunt, and Raven Hill, her ability was also frankly recognised when in turn she attacked the world of publishers. Her first patron was Mr. Darton, of the firm of Messrs. Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., by whose courtesy we are enabled to reproduce here the drawings from The Songs of Innocence.

The Little Boy Found. From The Songs of Innocence. By permission of Messrs. Wells Gardner, Darton & Co.

Coming to a consideration of the illustrations which accompany this article, the reader does not need to be told that, whatever may have been the artistic upbringing of the designer, there is little enough about them to suggest the rigid archaic convention which associates [238/39] itself with the name of Birmingham in eonnection with the decoration of books. Yet the stage of development at which these represent Miss Levetus has been preceded by a course of that beautiful, if unsatisfying, mediaevalism which one might naturally have expected. Possessed of strong individuality and force of character — for this the reader may take my word — Celia Levetus has been able to burst through the severity of a fine, if singularly limited, convention, all the better, perhaps, for the discipline which it imposed; while other pupils, less robust, have, it is to be feared, sometimes found the burden too heavy to be borne, and have sunk down into mere mannerism. Be that as it may, it is, of course, only when the artist has found herself that her work begins to be of interest in these pages. And so we find, comparing these drawings with what has been left behind, that the qualities she has set herself to gain include grace and flexibility of line, ease, and life-sparkle and sap, in short; and on the other hand, that she has sought to restrain that fatal tendency to over-decoration, not to mention a certain indifference to drawing so long as the decoration be right, that one has sometimes regretted in designs emanating from the school in question. The beauty of the decorative sense shown by the illustrations given, especially, perhaps, in the bookplate for Mr. Holman Hunt, and "The Angel" from The Songs of Experience will not be likely to be overlooked.

Left: "The Night is Worn.” From The Songs of Experience. By permission of Mr. David Nutt. Right: Title-Page to The Songs of Innocence. By permission of Messrs. Wells Gardner, Darton & Co.

I must not omit to acknowledge the kind permission of Mr. David Nutt to reproduce the drawings from The Songs of Experience, published by him. These designs in illustration of Blake should be considered upon their own merits and without comparison with his. Taken in this way it seems to me that they possess a distinct lyrical value, and are both harmonious in spirit with, and pertinent in feeling to, the Songs. It can be claimed for them that they are sincere and sympathetic, and of high technical value, and as such they are both interesting and legitimate. Whether Miss Levetus can be regarded as an example of the younger artists whom we may look for as a result of the unselfish labours of that distinctive and spontaneous Birmingham group of book decorators already referred to, it would hardly be safe to say. Yet it seems natural enough to suppose that their independence — which has certainly never been called in question — will breed independence in those who learn from them, and, as we cannot always remain at first principles, progress must result. After all, is it suflficiently borne in mind that, in those wonderful times when the other arts and crafts were blooming in perfect maturity, the art of book decoration was only in its infancy, the baby of the family? Is it not rather the art of our own time, the only one left for us to develop ? Of all the others the great masters of the past have laid down the governing principles, have created all the great masterpieces, have said almost the last word — architecture, painting, engraving, dyeing, carving, furniture-making, tapestry-weaving, and the rest.

In conclusion, I have but to add that Celia Eevetus herself conceived and suggested the idea of illustrating Blake, and is indeed one of those fortunate persons who execute very little work that is not to their taste.

H. W. Bromhead.

Bibliography

Bromhead, H. W. "An Illustrator of Blake." Art Journal. Vol. 62 (1900). Internet Archive. 237-39. Contributed by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 7 August 2020.

Created 7 August 2020