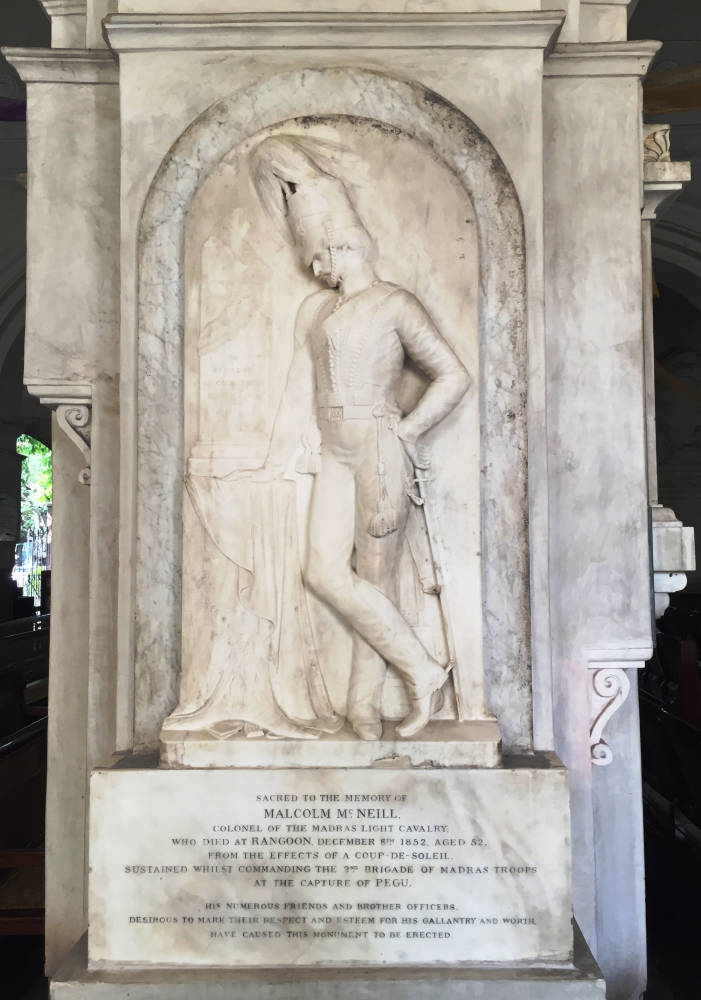

Memorial for Brigadier Malcolm McNeill

Edward Richardson

Commissioned 1853. Installed 1855

St Mary’s Church, Fort St George, Madras (Chennai)

St Mary’s Church in Fort St George is not only the earliest Anglican church in India but claims to be the first east of Suez, built in 1680. It is still one of the finest examples in India, designed to catch even the slightest hint of a breeze off the sea; a haven of relative coolness in the sweltering heat of a south Indian summer.

Related material

See commentary below.

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Inside the church is a plethora of memorials to officers and civilians of the East India Company who died far from home, sometimes in battle but more often from the combination of tropical heat and disease. One such is the memorial to Brigadier Malcolm McNeill of the Madras Light Cavalry. From a well-to-do family in Argyllshire he was born in 1800 and, after an education in Edinburgh, enlisted in the Madras Cavalry in 1819. In that year the eight regiments of Madras Native Cavalry were renamed as Madras Light Cavalry. They had been raised between 1784 and 1804 and most of them had served in the Mysore wars against Tippoo Sultan including at the epic Battle of Seringapatam where Tippoo was ultimately defeated and killed. The Madras Light Cavalry uniform is well portrayed in Edward Richardson’s sculpture. The officers and troopers wore light blue uniforms with red collars and cuffs.

His early career in the Madras Presidency (which comprised much of south eastern India) would have been relatively quiet. In 1823 he married Emily Bennett at Wallajahabad and they had numerous children, several of whom died in childhood. In 1831 we find him as a Captain in charge of the 6th Light Cavalry at Arcot (115km west of Madras). By 1842 he is Lieutenant Colonel in the 7th Light Cavalry at Madras and in 1843 he transferred to the 2nd Light Cavalry. Finally in 1852 he is described, in his last will and testament, as being in command at Vellore, the cantonment town about 20km west of Arcot, famous for its 1806 mutiny and for its huge 16th Century fort.

The Madras army of that period largely escaped involvement in the disastrous First Afghan War of the early 1840s. The Bombay Presidency bore the brunt of that ill-fated campaign. Indeed McNeill may have feared that his military career would end without being tested in serious combat. However in 1852 the Governor General Lord Dalhousie decided to punish the Burmese regime for its supposed insolence by seizing the province of Pegu to the north of Rangoon. For that purpose he sent Divisions from Bengal and Madras to Rangoon. Brigadier McNeill was given command of the 2nd Madras Brigade. The whole army came under the command of the 68 year old Major General Henry Thomas Godwin. Godwin had served in the Peninsular War under Wellington and had also taken part in the First Burma War in the 1820s. He was a true veteran, adored by his troops, but his management of the Pegu campaign was marked by extraordinary incompetence. He would die the following year (1853) at Simla from “exposure and over-exertion in Burma” (DNB).

There must have been a moment of joy for McNeill when Godwin nominated him to command the column to be sent north in 4 Bengal Marine steamers to recapture Pegu (modern Bago). The joy was brief because Godwin then announced that he would “accompany” McNeill “when it was to be expected with his accustomed energy he would superintend operations” (Laurie p.209). They set off on the 19th November under a broiling sun. Once at Pegu the Madras troops quickly captured Pegu after an appallingly arduous advance through thick jungle in oppressive heat.

According to W.F.B. Laurie’s book on the Burmese wars,

Our loss was three officers wounded, one, Lieutenant Cook, of the Commissariat, mortally; and from thirty five to forty of the men, Europeans and sepoys, were killed and wounded. Two or three officers were disabled by the sun, among them the worthy Brigadier, Malcolm McNeill. They were fighting from 7 a.m. till 1 p.m. All zealous soldiers should, we thought, come to this country and learn what fatigue is, fighting with the enemy in ambush, under a Burmese sun! [214]

Laurie adds that on 8th December the force “was saddened by the death of Brigadier McNeill.....He never recovered from the fatigue and exposure attending the capture. He was of the old school, an excellent and gallant officer, and a great favourite in the army.”

The inscription gives the reason for McNeill’s death as a ‘coup de soleil’. In this context it refers to sunstroke or heatstroke. Heatstroke is where the body is no longer able to cool itself and a person's body temperature becomes dangerously high (sunstroke is when this is caused by prolonged exposure to direct sunlight). According to the British National Health Service (NHS) website “Heat exhaustion or heatstroke can develop quickly over a few minutes, or gradually over several hours or days. If left untreated, more severe symptoms of heatstroke can develop, including confusion, disorientation, seizures (fits) and a loss of consciousness”. The best precautions, it continues, are to keep out of the sun between 11am and 3pm. If you have to go out in the heat, walk in the shade, avoid extreme physical exertion and wear light, loose-fitting cotton clothes. Drink plenty of cool drinks. We can safely say that McNeill would have failed on all counts.

McNeill did not live to witness the later events of the chaotic campaign. Godwin had left an insufficient Madras force to garrison Pegu and returned to Rangoon with the bulk of the force (and McNeill doubtless on a stretcher). Within days the garrison was being besieged and summoned help. A relief column was sent back to Pegu where in early December an action was fought near its huge Pagoda. Godwin then chased the enemy into the jungle before running out of supplies. He received much criticism for his conduct of operations from both the British and Indian press.

There is also a stained glass window to McNeill in the parish church of Alvechurch in Worcestershire where his daughter’s family honoured him. Before being shipped to Madras Richardson’s sculpture of McNeill was exhibited at the 87th (1855) Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition in London.

Sources

Blackwood, Robert Melvin. Battles of the British army. Chapter XXXVII. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1905.

Frontier and Overseas operations from India Volume V. Simla: Government Press, 1907. V, 91-99.

Godwin, Henry Thomas. Dictionary of National Biography 1885-1900 Volume 22.

“Heat exhaustion and heatstroke.” NHS Choices website.

Laurie, Colonel WFB. Our Burmese Wars. London: WH Allen, 1880.

McNeill memorial window. Remember the Fallen website.

“Relief of Brigadier Malcolm McNeill.” University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011.

Roscoe, Ingrid with Emma Hardy and MG Sullivan. A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain, 1660-1851. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Victorian

Web

British

India

Visual

Arts

Sculpture

Edward

Richardson

Next

Last modified 6 August 2017