Harry Bates, A.R.A., Psyche Being Borne Away by Zephyr central panel of Cupid and Psyche. (entire triptych) Plaster relief, 13 ½ x 29 ½ inches.

While Psyche wept upon the rock forsaken

Alone, despairing, dreading, - gradually

By Zephyrus she was enwrapt and taken

Still trembling, - like lilies planted high,-

Through all her fair white limbs. Her vesture spread,

Her very bosom eddying with surprise,-

He drew her slowly from the mountain-head . . .

Yet Love was not far off from all that Rest. — Elizabeth Barrett Browning “Psyche Wafted by Zepharus”

Bates, who was a prominent member in the New Sculpture movement, was probably the most devout classicist of the group. His work was influenced, not only by ancient Greek and Renaissance sculpture but also by current French romanto-realist sculpture and the Pre-Raphaelite, Aesthetic, Arts and Crafts, and Symbolist Movements. Bates was at his most skillful in the composition and sculpting of relief sculpture. It is in this particular medium that he produced his most technically advanced and aesthetically refined work and he executed some of the most complex examples of the late nineteenth century.

Bates’s triptych of The Story of Psyche in three silvered bronze bas-reliefs was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1887 [nos. 1854-56]. This sculptural relief was based on one of the last poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “Psyche Wafted by Zepharus,” and seems to have been influenced by the works of the painters Edward Burne-Jones and G. F. Watts. As John Christian has pointed out, "to this generation they were both grand old men of British symbolism, whose work not only exemplified the fusion of realism and idealism which the New Sculpture sought to achieve but provided a fertile mine of imagery” (85-86).

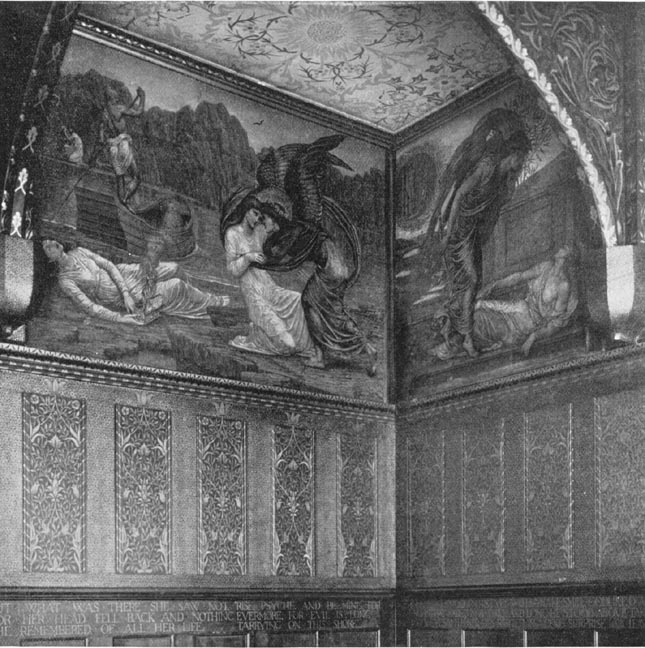

South West Corner, Cupid and Psyche Frieze by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Click on image to enlarge itj.

The central panel of Bates’ sculptural relief shows Psyche, who has been lulled into a stupor, being abducted from her desolate mountaintop by Zephyrus, the god of the west wind. In the left-hand panel Psyche is shown forsaken and alone, sitting on a rock, and trying to tie a fillet around her head. In the right-hand panel Cupid is shown kneeling, eager and expectant, and waiting for Psyche. Burne-Jones had long been interested in the story of Cupid and Psyche. In the 1860s he had designed a series of illustrations on this theme for William Morris's The Earthly Paradise, including a design for Zephyrus and Psyche dating from 1864. In 1872 Burne-Jones began a series of Cupid and Psyche decorations for George Howard’s dining room at his London home No. 1 Palace Green. Robert Upstone has also pointed out Bates’s indebtedness to both Burne-Jones and Watts in this sculptural relief (91). Although Psyche in the central panel of Bates's The Story of Psyche is nude, the pose of the figure is virtually identical with that of Psyche in Burne-Jones' Cupid finding Psyche of 1865-87, in the collection of the Manchester Art Gallery. The figure of Cupid in the right-hand panel was also obviously influenced by Burne-Jones' painting of Cupid finding Psyche, although Bates' Cupid is crouching rather than bending.

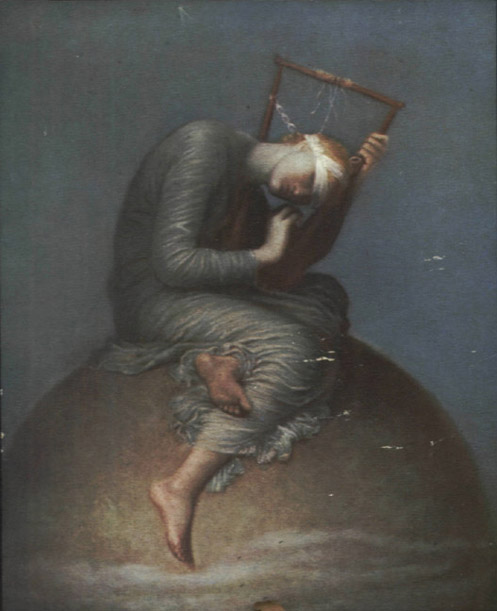

Hope by G. F. Watts.

The figure of Psyche in the left-hand panel appears to be derived from Watts's painting Hope, which had been exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1886, the year prior to Bates's sculptural triptych being shown at the Royal Academy. The figure of Zephyrus in the central relief owes much to the figure of Death in Watts' painting Love and Death. It is possible that the model for Psyche in Bates’s relief was Louise “Louie” Luker (1873-1971), who later became a professional artist herself.

The Story of Psyche received favourable reviews when the triptych was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1887. The critic for The Magazine of Art, for instance, commented: “Among designs in low relief, Mr. Harry Bates is without competitor, for there is nothing that approaches within measurable distance the imagination and fine feeling for the antique that mark Mr. Bates’s three beautiful panels illustrating the story of Psyche” (383).

Casts of this relief were available in in at least two sizes and in different mediums, including plaster, marble, bronze, and silvered bronze. The large silvered bronze version exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1887 is at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. Large plaster versions of this triptych in a wooden frame are in the collections of the Glasgow Museums Resource Centre and the Musée d' Orsay in Paris. A plaster relief of Psyche in a gilt wood frame is in the collection of the Mougins Musée d’Art Classique, Mougins, France. Photographic replicas were also made as platinotypes by Frederick Hollyer, one of which appears in this section of the Victorian Wewb.

Related Material

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Robert Bowman and the Fine Art Society, London, have most generously given their permission to use information, images, and text from Sir Alfred Gilbert and the New Sculpture in the Victorian Web. Copyright on text and images from their catalogues remains, of course, with them. [GPL]

Bibliography

Beattie, Susan. The New Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. pl 147.

Bowman, Robert. Sir Alfred Gilbert and the New Sculpture. London: The Fine Art Society, 2008. Pp. 6-7.

Christian, John. “Burne-Jones and Sculpture,” in Benedict Read and Joanna Barnes, [Eds.]. Pre-Raphaelite Sculpture, London: Lund Humphries, (1991): 77-91.

“Current Art. –IV,” The Magazine of Art 10 (1887): 376-84.

Upstone, Robert. “Symbolism in Three Dimensions” in Andrew Wilton and Upstone, Robert [Eds.] The Age of Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Watts Symbolism in Britain 1860-1910. London: The Tate Gallery Publications, 1997. 83-92.

Last modified 7 June 2008