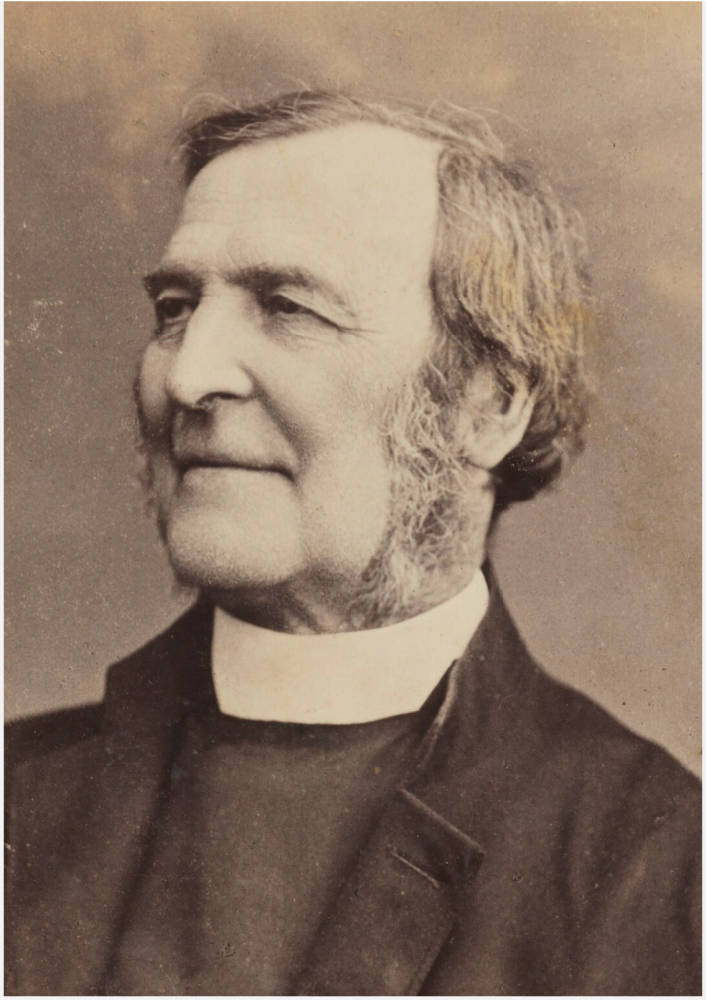

Frederick Temple. Photographers: James Russell & Sons Albumen print. c 1896. Reproduced with permission of The National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG P1700. Given by Martin Plaut, 2012. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Near the close of "The Education of the World," the first essay in the controversial Essays and Reviews (1860), Frederick Temple sets forth a view of scripture that simultaneously draws upon fundamental points of Christian belief, such as the opposition of flesh and spirit, shared by many of his most religiously conservative readers and yet presents conclusions that many of them believed would destroy Christianity. Like Victorian Christians of all denominations, Temple emphasizes that the Bible provides an historical record perfectly suited to the needs of contemporary believers. He also describes it in a most traditional manner as "a supreme authority," but his Protestant emphasis upon the individual conscience leads to some most untraditional — some would say blasphemous — conclusions:

Had the Bible been drawn up in precise statements of faith, or detailed precepts of conduct, we should have had no alternative but either permanent subjection to an outer law, or loss of the highest instrument of self-education. But the Bible, from its very form, is exactly adapted to our present historical want. It is a history; even the doctrinal parts of it are cast in a historical form, and are best studied by considering them as records of the time at which they were written, and as conveying to us the highest and greatest religious life of that time. Hence we use the Bible — some consciously, some unconsciously — not to over-ride, but to evoke the voice of conscience. When conscience and the Bible appear to differ, the pious Christian immediately concludes that he has not understood the Bible. Hence, too, while the interpretation of the Bible varies from age to age, it varies always in one dimension. The schoolmen found Purgatory in it. Later students found enough to condemn Galileo. Not so long ago it would have been held to condemn geology, and there are many who do so interpret it. The current is all one way — it evidently points to the identification of the Bible with the voice of conscience. The Bible is, in fact, hindered by its form from exercising a despotism over the human spirit; if it could do that, it would become the outer law at once; but its form is so admirably adapted to our need, that it wins from all of us the reverence of a supreme authority, and yet imposes on us no yoke of subjection. This it does by virtue of the principle of private judgement, which puts conscience between us and the Bible, making conscience the supreme interpreter, whom it may be a duty to enlighten, but whom it can never be a duty to disobey. [163]

Evangelicals and Tractarians alike would accept Temple's statement that the Bible "is a history," but neither would accept his principle of biblical interpretation: "When conscience and the Bible appear to differ, the pious Christian immediately concludes that he has not understood the Bible." The age-old principle of interpretation would have that "when points of Christian belief and the Bible appear to differ, the pious Christian immediately concludes that he has not understood the Bible."

In fact, Temple's ultra-Protestant position clearly puts individual conscience above scripture. Although he accepts the idea that the Bible is in some sense divinely inspired, he believes that inspiration does not make the biblical text literally true. Like many other Broad Churchmen, Temple emphasizes that the Bible must be interpreted metaphorically rather than literally, but few others state so baldly that one of the best things about it is an essential vagueness that, in his words, keeps it "from exercising a despotism over the human spirit." In other words, we revere the Bible, but we can "disobey" it whenever it conflicts with our feelings or beliefs.

Related Readings

The University of Virginia Press has recently published a modern edition: Essays and Reviews: The 1860 Text and Its Reading edited by Victor Shea and William Whitla. 1,056 pages; 25 b&w illustrations; ISBN 0-8139-1869-3 $90.00.

Last modified December 2003

Image added 11 March 2020