Apart from the first, the illustrations here are taken from our own website. Click on the images to enlarge them and for more information about them.

Narratives of the history of religion in Victorian Britain typically focus on the big picture. Historians explain the day's spiritual scene by sorting out the major denominations, parties, movements, and -isms; thus the period appears the collision and occasional collaboration between Evangelicals, Broad Churchmen, Tractarians, Dissenters, etc. Another familiar strategy is to outline the period's religious controversies and developments by way of the lives and opinions of leading clerical figures, such as John Henry Newman, John Colenso, Edward Pusey, F. D. Maurice, and Charles Spurgeon, among many others. Yet by reporting on Victorian religion in such a "top-down" manner, we often inadvertently obscure the lived realities of the ground-level business of Victorian religious expression, particularly the day-to-day, or better said, Sunday-to-Sunday labors of those who presided over the Victorians' worship services. In A Victorian Curate: A Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. Dr John Hunt, David Yeandle, Emeritus Professor of German at King's College, London, offers a valuable view of the Victorian religious life from the bottom up, focusing, as the title announces, on the travails of the Scottish Anglican curate John Hunt (1827-1907).

As Yeandle explains, Hunt possessed both the learning and industry to produce a number of lengthy works of scholarship, including his multi-volume study Religious Thought in England, and on the strength of that work would in time earn some recognition as a member of the liberal (Yeandle calls its "progressive") wing of the Church of England. His eventual attainment of a benefice (i.e. permanent living) — in the Kentish village of Otford — was due to the intercession of the likeminded Broad-churchman Arthur Stanley, Dean of Westminster. Yet Yeandle's interest is not in Hunt the comfortably situated vicar or Hunt the historian of English religious thought. Yeandle's study focuses on the star-crossed early years of Hunt's clerical career when he struggled to secure steady employment as a curate. The biographer follows Hunt's lead in this endeavor, as the clergyman had published what Yeandle calls a "somewhat disgruntled and dejected account of his career to date" in 1865 in the form of an anonymously published pamphlet, Clergymen Made Scarce, the second edition of which (1867) was circulated widely enough to be mentioned in some noteworthy periodicals.

John Everett Millais's depiction of Mr Crawley, the much

put-upon curate of Anthony Trollope's Barsetshire

Chronicles, with his long-suffering family.

Most of the book's chapters strive to bring the incidents reported in the pamphlet to life. Hunt had wisely, it seems, made the decision not to name names, disguising the persons with whom he interacted and places his visited through the use of pseudonyms and vague geographical references. Yeandle, however, is able to crack the code thanks to his access to a copy annotated by Hunt's first wife, Eliza. Yeandle leads the reader through the various stops on Hunt's quest to find employment, beginning with a short, though happy, first curacy in Bishopwearmouth, Sunderland in the north of England, through several, mostly unhappy stops in London and its environs, and ending, as the pamphlet does, with a moderately happy appointment in St. Ives, Huntingdonshire. (Hunt would, as Yeandle explains, serve in two further curacies--St Mary’s, Lambeth, and at St Nicholas’s, Sutton, in Surrey — before taking up the living in Otford.) Across the chapters, the reader thus follows Hunt from advertisement to advertisement, from interview to interview, and from appointment to appointment, some lasting only a few months.

The principal themes of Hunt's wanderings, as Yeandle points out, are the precarious lot of the curate and the complicated system of patronage and preferment that determined the courses of Victorian churchmen's careers. On the first point, we need to recognize that the word "curate" had two principal designations in the Victorian period. The first applied to so-called "perpetual curates" who had basically same responsibilities as a vicar or rector within a parish but who received a cash stipend rather, as with a vicar or rector, an allotment tied directly to the parish's tithes. Curates of the second kind — Yeandle's concern — were often called "assistant curates." These were priests who were subcontracted by a rector or vicar to handle clerical tasks such as helping out with certain parts of a worship service or conducting services in the incumbent priest's absence. Yeandle's account shows that the curate's life wasn't difficult simply due to often insufficient wages and the temporary nature of employment. Hunt's experiences highlight the degree to which a curate was at the mercy of the incumbent, and not only in determining the length of the position and the responsibilities he'd perform (for example, Hunt liked to preach but wasn't always permitted to do so). The incumbent could also influence a curate's subsequent trajectory by putting in an ill-word when asked for a reference by a prospective employer or an aid organization, such as the Pastoral Aid Society, which supplemented the pay of curates like Hunt.

The problem of references leads us to the other theme — patronage and preferment. Incumbents represented a sort of informal network whose good or bad opinion of a curate could propel a young priest's rise or ensure that the priest would toil for years. The Pastoral Aid Society, meanwhile, was a larger sort of corporate patron, existing to help curates along in conditions when the incumbent couldn't pay what we'd now call a "living wage." The trouble for the liberal-minded Hunt was that the Society had a distinct Evangelical flavor, and so a wrong word from an incumbent about his "heterodox" views could sink his application for support. As a Scot educated in a Perth grammar school and at the University of St. Andrews (from which he doesn't seem to have taken a degree), moreover, Hunt was at a disadvantage when he arrived in England because he had no preexisting network of classmates, professors, or ecclesiastical sponsors. Yeandle suggests that some of the incumbents who turned Hunt away may have been bigoted against Scots. His appeals to clerics higher up the hierarchy were not heeded — at last not at this point in his career. Even in situations where the congregation clearly favored Hunt, our hero lacked either the clerical or the financial backing to procure the benefice. (A particularly instructive account of how benefices controlled by lay persons could be bought appears in the final narrative chapter, "St Ives, Hunts.") Again and again, Yeandle uses Hunt as a negative case study to illustrate the qualities that made for a winning formula for advancement.

The Free Church, St Ives, today.

My summary so far may seem to suggest that A Victorian Curate is soul-sapping read from start to finish. But Hunt had his share of wit, and Yeandle clearly does too. Clergymen Made Scarce is more parts satire than diatribe, Hunt seeing clearly — and wishing his reader to see — how ludicrous his experiences were given both his education and his earnest desire to serve. Such a situation is ripe for irony, and Yeandle is highly sensitive to the many ironies of Hunt's life as well as to the quirks of his hero and his interlocutors. Hunt's peregrinations bring him into contact with numerous clerical personages and church communities that would be totally at home in a novel by Anthony Trollope or George Eliot. In his account of St. Ives, for example, Hunt mentions that "[i]t was emphatically a Dissenting town," featuring "but one Church, while there were seven or eight meeting houses [...] One of them, indeed, was called the Free Church, a fine Gothic building, with a tall spire, and stained-glass windows, erected at an expense of £5000." The whole building, Yeandle explains, was to be paid for by a Quaker convert named Potto Brown, but Brown didn't think that a Free Church ought to have a steeple, so he only gave £3000, leaving the rest of the congregation to make up the difference. Later, Hunt reports on the effect of a rumor that a local solicitor, one Martin Hunnybun (Hunt's pseudonym is "Mr. Sweetbread"), might purchase the living for his son, "a curate of All Saints’, Margaret Street, London [...] a bastion of Anglo-Catholicism, a concept that, at the time, was alien to St Ives." Hunt continues:

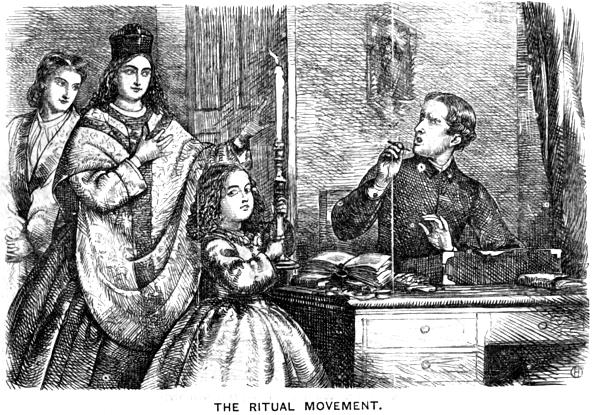

The town was petrified with horror. Men’s faces turned pale, and even women shuddered at the approaching spiritual calamity. Then there were visions of priests clothed in albs and copes and chasubles; visions of incense and altars, acolytes and thurifers, lighted candles, holy water, rood lofts, altar screens, crosses, crucifixes, and mimic Virgin Marys.

The spiritual calamity did not take place, as Hunnybun decided that the price to acquire the benefice was too steep. Passages like this pepper Yeandle's book, allowing us to see not only Hunt's (and Yeandle's) sense of humor but also reminding us of the complicated landscape of parties and prejudices that a curate had to navigate when shifting between positions.

A Punch cartoon makes fun of a High Churchman, who is startled when his wife and daughters dress up in the new vestments, putting on a "show" for him (1866).

Yeandle is to be credited in several respects for this study. Most importantly, he has done us all a service in illustrating the plight of the lowest tier of the clergy, the curate. The whole apparatus of the Church of England takes on a different hue when we look at it from the ground up. But the way that Yeandle constructs his study is also notable. The narrative portion runs to about one hundred pages, which seemed to this reader at least exactly the right length to do justice to his subject matter. The remainder of the book consists of various Victorian-era documents that might be of interest to readers engaged by Yeandle's account, including the text of Clergymen Made Scarce, reviews of Hunt's writings, and contemporary reports (including a Punch piece) on a minor scandal that erupted when it was discovered that Hunt planned to undertake anatomical study of an unborn fetus.

Traditionally, biographies of a minor churchman were destined either to languish in a university library or to be stored, albeit more lovingly, on a parish book shelf. Yeandle, in fact, references studies of both varieties in his notes. This book, though, has been published by Open Book Publishers, meaning that all of these materials are fully available for online perusal without charge this very moment. It is, in other words, a book published in the same "open" spirit as Victorian Web. Readers interested in gaining a fresh perspective on Victorian religious life will be well rewarded by accepting its invitation to read freely.

Bibliography

Hunt, John. Clergymen Made Scarce. 2nd Ed. London: Hall and Co., 1867.

Yeandle, David. A Victorian Curate: A Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. Dr John Hunt. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2021.

Created 1 June 2021