This review is reproduced here by kind permission of Professor Bury and the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where the review was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. [Click on the following images for larger pictures and for more information about them when available.]

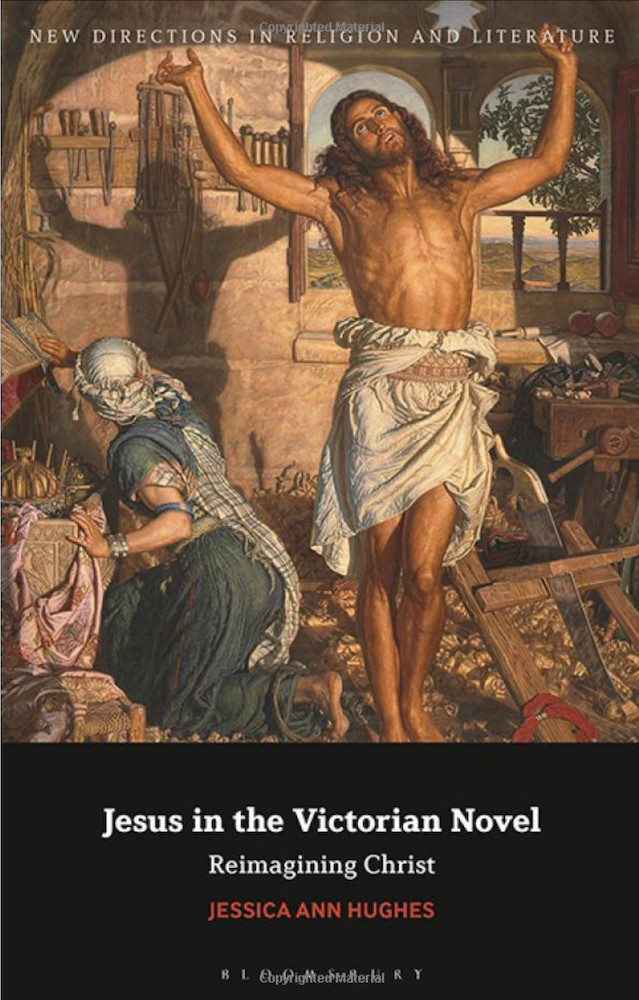

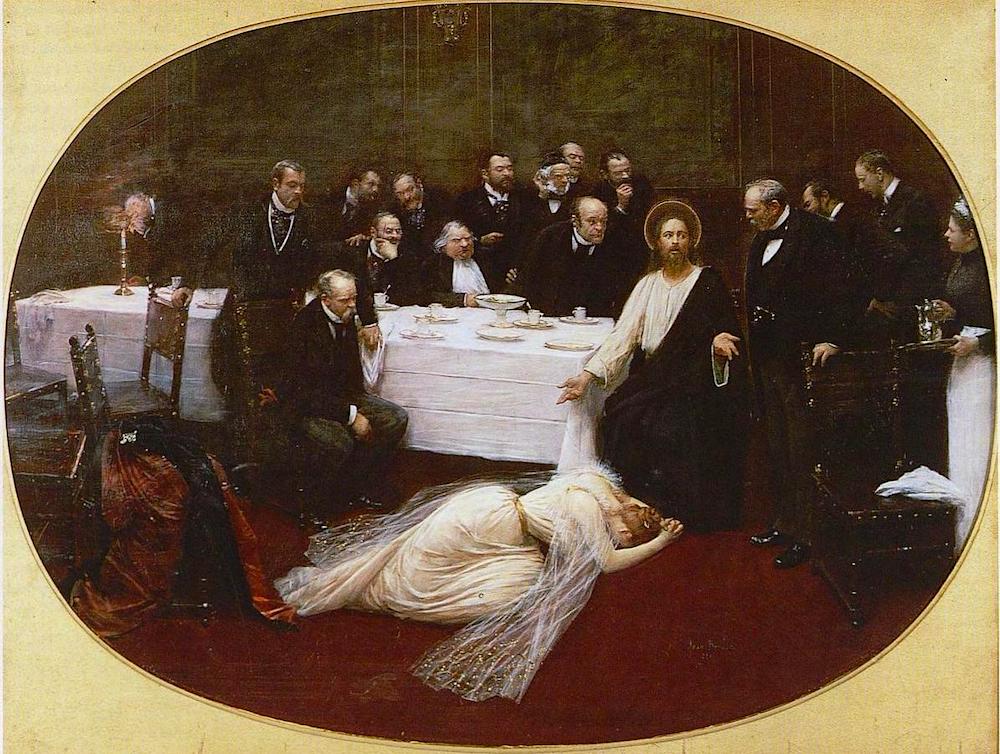

As it was, in the mind of the artist, a historically accurate reconstruction of what Christ looked like in the first century, The Shadow of Death by William Holman Hunt may not been the best of iconographic choices for the cover of a book which claims to study “instances in realist novels where Jesus appears as himself to characters in the Victorian period, even if simultaneously embodied in other characters” (6). Perhaps the ambition of Jessica Ann Hughes’ book would have been more adequately illustrated by a painting like Jean Béraud’s The Magdalene at the House of the Pharisee (Paris, Musée d’Orsay), where Christ appears in an assembly of frock-coated gentlemen, among whom features Renan, the author of a controversial Vie de Jésus in 1863. Jesus in the Victorian Novel is neither about novels like Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), where the hero’s path crosses that of Jesus in Jerusalem, nor about such works as depict the self-sacrifice of a Christ-like character. It focuses on the “Jesus redivivus” type of story, in which writers “more readily identified with humanism and atheism” tried to imagine “what an encounter with Jesus as a real, present, embodied character might look like” (7) in the nineteenth century.

Possibly more relevant here: Jean Béraud’s The Magdalene at the House of the Pharisee: Christ appearing in an assembly of frock-coated gentlemen, one of them in the likeness of Ernest Renan, the author of a controversial Vie de Jésus (1863). Source: Offenstadt 369.

The first chapter develops the notion of “substitionary atonement,” in which Jesus pays for humanity’s crimes against God, in parallel with Michael McKeon’s idea of narrative atonement in fictional autobiographies, where the character and the narrator are finally fused through reconciliation with other characters or with Jesus. Next comes a discussion of popular piety and the repackaging of the evangelical message in novels which tried to depict Jesus’ everyday life “when he is not dying for the sins of the world” (52). The works of David Friedrich Strauss and Ernest Renan demythologised Christ at a time of disturbing scientific discoveries and biblical scholarship, making it even harder to introduce Jesus “as a relatable novel character” (65).

Chapters 3 to 5 are devoted to four novels in which Christ appears under different guises. In Charles Kingsley’s Alton Locke (1849), “a working-class conversion narrative” (81), the hero’s final dream includes a vision of Jesus as a “revolutionary king” but also as an almost ordinary human being. The difficulty for Kingsley was to overcome the problem of incarnation so as to make the encounter convincing; when beheld by Alton on his sickbed, in his dream of a surreal world, Jesus is “dynamic and relational” (95), a real man with whom he can interact, a real person with whom he can be in dialogue, a frustrated character with whom the working-class protagonist can sympathise.

Left: Adam Bede at work in the carpenter's shop, in William Small's frontispiece illustration for George Eliot's novel. Right: Robert Elsmere's faith being sorely tried as he falls under the influence of the free-thinking to Squire Wendover.

In George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859), Jesus is the “reconciling high priest,” the virtuous mediator between God and mankind. As a rival for Christ in the heart of lay preacher Dinah, carpenter Adam himself becomes a possible version of Jesus in real life: an exemplary man in his uncompromised masculinity, embodying justice and mercy, a “demythologised, Feuerbachean model of Jesus” (128). An active peacemaker, Adam suffers to save and reconcile other people, as opposed to Dinah’s more ethereal conception of Jesus. “Ultimately, Eliot is able to reimagine the atonement as a commonplace heroic grounded in restorative justice” (130).

Jesus as a moral prophet, “an impossibly idealistic dreamer who disrupts people’s expectations” [131], is present in two later novels: The True History of Joshua Davidson, Christian and Communist (1872) by Eliza Lynn Linton, and Robert Elsmere (1888) by “Mrs Humphry Ward,” Mary Augusta Arnold, Matthew Arnold’s niece. Joshua Davidson decides to live the gospel out in his everyday life, “a highly literal translation that, while accommodating some realities of the nineteenth century like the existence of communism, loses the idea of the original in its very literalness” (142). Having rescued a prostitute and a drunkard and created a sort of religious commune, Davidson is eventually stoned to death. Robert Elsmere’s life is more an imitation, a paraphrase of Christ’s life, enacting His ideals in the modern world. “Robert’s demythologised faith is ultimately authorised by his own mystical encounter with Jesus” (146) but he finally understands that there is no future for prophets.

In her conclusion, Jessica Ann Hughes shows that, while Christian novels have continued to be published all through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, such fictional encounters with Jesus reflected “the Victorian longing for an aesthetics capable of representing epistemic coherence, reconciliation, and salvation” (173).

Bibliography

Hughes, Jessica Ann. Jesus in the Victorian Novel: Reimagining Christ. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022. Hardback, 190pp. ISBN 978-1350278158. £85

[Illustration source] Offenenstadt, Patrick. The Belle Époque: A Dream of Times Gone By. Taschen/Wildenstein Institute: Köln, 1999. Internet Archive. Released on the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International Creative Commons License.

Crested 21 March 2022