[Thanks to James Heffernan, founder and editor-in-chief of Review 19 for sharing this review with readers of the Victorian Web. — Katherine Miller Weber]

n the inaugural posting of New Books on Literature 19 [outside the Victorian Web], a project devoted to the timely reviewing of recent works in the field of nineteenth-century literature, it seems especially appropriate to consider a work that directly addresses the unique discursive and material qualities of the periodical. The very word "periodical" bespeaks both its evanescence and its power to reflect the fleeting preoccupations, tensions, and material interests of the period in which it is produced. These qualities, as Kathyrn Ledbetter has demonstrated in her earlier work, not only help to situate the periodical as a rich source of insight into individual works of literature, but also make possible a more supple understanding of how cultural meaning is created in print. In "Colour'd Shadows": Contexts in Publishing, Printing, and Reading Nineteenth-Century British Women Writers (Palgrave, 2005), Ledbetter and Terence Allan Hoagwood attempted "to show in practice ways to unfold multiple meanings of literary work including meanings that the physical form of the work creates, and meanings that arise as the book circulates in material exchanges" (3). Ledbetter's next book, Tennyson and Victorian Periodicals: Commodities in Context (Palgrave, 2007) showed how the periodical press often transformed poetic meaning by treating poetry as a commercial commodity.

n the inaugural posting of New Books on Literature 19 [outside the Victorian Web], a project devoted to the timely reviewing of recent works in the field of nineteenth-century literature, it seems especially appropriate to consider a work that directly addresses the unique discursive and material qualities of the periodical. The very word "periodical" bespeaks both its evanescence and its power to reflect the fleeting preoccupations, tensions, and material interests of the period in which it is produced. These qualities, as Kathyrn Ledbetter has demonstrated in her earlier work, not only help to situate the periodical as a rich source of insight into individual works of literature, but also make possible a more supple understanding of how cultural meaning is created in print. In "Colour'd Shadows": Contexts in Publishing, Printing, and Reading Nineteenth-Century British Women Writers (Palgrave, 2005), Ledbetter and Terence Allan Hoagwood attempted "to show in practice ways to unfold multiple meanings of literary work including meanings that the physical form of the work creates, and meanings that arise as the book circulates in material exchanges" (3). Ledbetter's next book, Tennyson and Victorian Periodicals: Commodities in Context (Palgrave, 2007) showed how the periodical press often transformed poetic meaning by treating poetry as a commercial commodity.

Ledbetter's engagement with the material history and discursive variety of periodical writing continues unabated in the present volume. While following up on the issues she has treated before, Ledbetter now trains our attention more pointedly on the gender politics of print culture. An accruing interest in nineteenth-century women's periodicals [outside the Victorian Web] has found expression over the last decade in countless volumes of literary and historical scholarship. It is a field of research that Ledbetter (as editor of Victorian Periodicals Review [outside the Victorian Web] has been instrumental in forging. An abbreviated list of recent titles in the field would have to include Margaret Beetham's A Magazine of Her Own?: Domesticity and Desire in the Woman's Magazine, 1800-1914 (Routledge, 1996), Barbara Onslow's Women of the Press in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Palgrave, 2001), Jennifer Phegley's Educating the Proper Woman Reader: Victorian Family Literary Magazines and Culture Health of the Nation (Ohio State UP, 2004), and the recent volume edited by Hilary Fraser, Stephanie Green, and Judith Johnston, Gender and the Victorian Periodical (Cambridge UP, 2008). For the most part, these publications have focused on the evolving discourses of feminism, the dynamics of public authorship, and the periodical's role as purveyor of both normative and radical positions on nineteenth-century gender roles. Only recently have scholars begun to examine the discursive vitality and interplay among poetry, image, and the periodical essay.

In her new book, Ledbetter considers how the generic variety of the women's periodical enabled the poetry published within its pages to reflect the real complexity of Victorian approaches to the ideology of "separate spheres." Though we might regard Victorian women's magazines as complicit in reinforcing subordinate roles for women, Ledbetter argues that they were sites of empowerment speaking directly to women's status as laborers (both domestic and public), religious and moral leaders, and organizers of intellectual culture. Reading women's periodical poems in context, Ledbetter stresses the importance of treating the verses published in these magazines in their proper context, as poems that engage in both conscious and unconscious ways with the visual and textual contributions that appear alongside them.

Treating the periodical on its own terms almost requires a new way of reading, and Ledbetter, always careful to balance methodology against critical practice, addresses this concern right from the beginning. In the Preface, she quotes what she describes as a more or less typical example of women's periodical poetry, Dewey M. Bailey's "Treasures." Though Ledbetter foresees that most readers will find the poem repulsively sentimental, as she herself did, she provocatively argues that even ostensibly "bad" poetry can be morally and politically salient. This is not simply to say that we should re-examine poems we once might have dismissed out of hand. Rather, Ledbetter proposes, we should "read the poetry within its own cultural system," which means both admitting the popularity and efficacy of sentimental writing among Victorian readers and recognizing the material context in which these poems appeared - namely, the periodical (9).

This is, I think, a more revolutionary and persuasive intervention than one might initially suppose. After all, Ledbetter is essentially asking contemporary scholars to suspend ingrained aesthetic sensibilities and to imagine instead what it might be like to read as a Victorian. This leads to some interesting interpretive moments, since many of the poems included in this volume do not appear, at first glance, to invite extensive analysis. Ledbetter, however, demonstrates that there is more than one way of interpreting a poem and retrains our attention on how the experience of these verses is informed by the essays, illustrations, short stories, and advertisements that literally surround them on all sides.

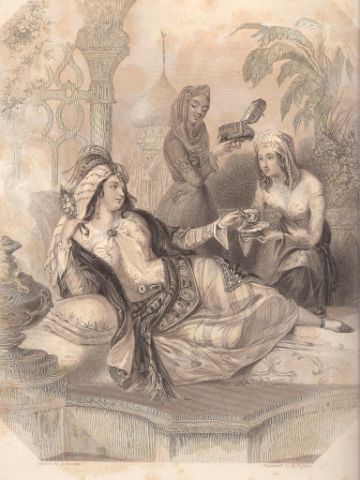

A good example of this is her discussion of the relationship between the Countess of Blessington's poem "The Bath" and its accompanying illustration, a picture entitled "Persia" (103) [at right]. Depicting a woman ensconced in Eastern luxury, the picture is a site of marked "gender confusion" evoking both domestic quietude and sensuality, both eroticized femininity and symbols of masculine desire (102). Consequently, even as the illustration invites the viewer to fantasize about a far-off land of exotic opulence, it also affords a clarifying glimpse into the relative instability of social categories that are usually taken for granted. Like the accompanying image, the poem is a site of discursive conflict, recording a conversation between Sultana, who likens her married life to that of a "prisoned bird," and two women who are inclined to romanticize Sultana's status and luxury. As Ledbetter points out, the pairing of image and text here yields conflicting outlooks on domesticity, inviting the female reader both to romanticize the Victorian home and to "explore the limits of that ideology" (104). Through the combination of the visual text and the poem, genuine reverence for the exemplary wife and mother thus merges with a healthy skepticism toward the Victorian cult of domesticity. Ledbetter's argument here is aptly nuanced. Rather than classifying the women's periodicals as disseminating propaganda for either radical feminism or conservative gender politics, she suggests instead that the dialogue between image and text provokes a range of interpretations and responses—that its value rests, appropriately enough, in generating precisely the kind of dialogue featured in Blessington's poem.

In some respects, Ledbetter's arguments about women writers, editors, and poets revive an older model of feminist interpretation, one that finds subversive gestures in unexpected places. The poetry featured in women's magazines, she observes, complicates the ideology of separate spheres, expressing private sentiments in a comparatively public space and helping us see important connections between domestic virtue and the public world of letters. At first, this approach may seem all too familiar, as when Ledbetter contends that the women's periodical served as a vehicle for promoting moral and civic improvement—in other words, that the periodical became an extension of woman's traditional role as the preserver of "the moral fiber of the nation" (24). Yet this tactic is part of a strategy that complicates older models of feminist thought. Wisely reluctant to ascribe to the periodical any single approach to gender, Ledbetter stresses "the conflicting, unstable characteristics of nineteenth-century domestic ideology and femininity" (66). Perhaps the most striking of Ledbetter's claims is what she identifies as the source of this instability. "Women are invited," she explains, "to explore intellectual topics within the textual environment of a domestic periodical for women, but the liberation that occurs ironically enables the instability of the separate spheres distinction that supposedly tethers the women readers and writers to their domestic domain" (77). In other words, the rhetoric of female domesticity in these periodicals often contained within it the seeds of liberation. To return to the example of woman's civilizing mission, "the periodicals promote traditional conservative Christian values that restrict women to the domestic space while leading them out of that space into public activism" (77).

The chief value of this book, then, lies in its methodological claims on behalf of a more nuanced approach to women's literature as well as to the unique possibilities afforded by the periodical itself. Throughout the book, Ledbetter draws attention to the difficulties of working with periodical archives, a struggle familiar to anyone who has ever attempted the task. The efforts of the scholar interested in periodical culture are consistently frustrated by the practice of anonymous publishing (which makes it difficult to identify specific authors), the sheer quantity of periodicals that emerged in the nineteenth century, and (paradoxically) the limited number that have survived for our own use. If presenting a documentary history of poetry in women's periodicals seemed "simple enough" at the beginning, Ledbetter frankly admits that her own research process was anything but simple: "The need for firm generalizations was constantly challenged by examples that did not fit comfortably within the definitions of one theme or form" (205-6). Although these hurdles may preclude making any sweeping claims on behalf of women's periodicals, they also seem to have opened up a space for engaging in a different kind of literary history. The range of periodicals, poetry, and experiences described in Ledbetter's account becomes not a source of obfuscation but a daunting challenge to current approaches to gender. Instead of neatly accommodating contemporary feminist vocabularies and schools of thought, nineteenth-century periodicals display a wide range of overlapping, contingent, and conflicting perspectives.

This interest in discursive variety is one Ledbetter shares with other scholars of Victorian journalism and print culture. Margaret Beetham (whose A Magazine of Her Own? is frequently cited by Ledbetter) argues that "the heterogeneous form of the magazine had always allowed contradictory discourses to coexist" (140). But whereas Beetham aims to demonstrate how fashion, beauty, and representations of the female body in women's magazines shaped a variety of attitudes toward women, Ledbetter seeks to show how the generic interplay between poetry and other constituent elements of the periodical embodied the promise of social reform. This important distinction puts Ledbetter's book in dialogue with recent works not specifically focused on women's periodicals—books such as Laurel Brake and Julie F. Codell's Encounters in the Victorian Press: Editors, Authors, Readers (Palgrave, 2005) or Dallas Liddle's The Dynamics of Genre: Journalism and the Practice of Literature in Mid-Victorian Britain (University of Virginia Press, 2009). In both of these works, the periodical press emerges as a space that juxtaposes conflicting points of view and cultural languages, sometimes with startling results.

Ledbetter's work elegantly dovetails with these perspectives. While recognizing the coexistence of opposing viewpoints within a single periodical issue, it resists perfunctory conclusions about the political positions one might expect women's periodicals to espouse. For instance, Ledbetter points out that a reviewer for The English Woman's Journal, a somewhat progressive periodical that emerged out of Anna Jameson's Langham Place Group, actually lauded Coventry Patmore's idealization of female domesticity in The Angel in the House (text), a fact that may come as some surprise to scholars who regard the poem "as an extreme example of the limitations Victorian women experienced in marriage" (36). As Ledbetter reminds us, "the important element of Patmore's poem to this reviewer is not that he portrays Honoria as a prisoner of patriarchal ideology [...] but that her lover shows appropriately authentic respect for her" (36). In this instance, Ledbetter makes a compelling case for evaluating women's periodicals with fresh eyes and without necessarily applying modern feminist sensibilities to them. If there is more than one way of reading a poem, Ledbetter seems to imply, there was also more than one way of pursuing the advancement of women in the nineteenth century.

By the same token, openly accepting the discursive variety of the women's periodical inevitably prompts further questions. What, for instance, would happen if we were to think about the EWJ review not merely in the context of the women's periodical, but in light of periodical culture writ large? If women's periodicals complicated the notion of separate spheres through their discursive variety, did other periodicals at this time do the same? Perhaps more importantly, one wonders whether the dynamic interchange that so often transpired among periodicals had any impact on the publications discussed in Ledbetter's account.

None of this is to suggest that Ledbetter could or should have addressed these questions in the space of a single volume: that would be an ambitious undertaking indeed. She accomplishes much of great value here for scholars of Victorian literature, gender studies, periodical history, poetry, and media studies. In covering so many fields of inquiry, Ledbetter has rightly circumscribed her subject, and I expect that readers will find her frankness regarding both the nature of periodical research and the real complexity of the Victorian intellectual landscape refreshing. What I am suggesting is that Ledbetter's book might also serve as an invitation to other scholars to consider how the category of "women's periodical" fits into the larger discursive field of nineteenth-century letters. Such an approach would be of great value in closing the gap between the allegedly separate spheres of male and female influence in the nineteenth century, a project Ledbetter pursues admirably in this insightful work.

Bibliography

Kathryn Ledbetter British Victorian Women's Periodicals: Beauty, Civilization, Poetry. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. xiii + 236 pp.

Last modified 11 July 2014