[Once a student at the University of Genoa in Piedmont, and then a young lawyer who joined the secret independence movement, the Carbonari in 1830, Giuseppe (Joseph) Mazzini (1805-1872) became the founder of Young Italy, the Prophet of Risorgimento, and the Soul of Italy. His father, a university professor, was something of a Jacobin when Genoa was part of the Ligurian Republic; and he was an ardent republican hoped first to liberate the Italian peninsula from foreign domination and the theocracy of the Pope, unite the disparate states and principalities into a modern republic, and then touch off republican revolutions across Europe; he disapproved of the united Kingdom of Italy (1861) because it was not a true republic, but a constitutional monarchy based on the models of Piedmont and Great Britain. Driven out of his native land in the 1830s, he moved to Switzerland and then Marseilles, the subject of bureaucratic oversight and close scrutiny by the authorities. Mazzini settled for a lengthy period in England (beginning in July, 1837), supporting himself by teaching while engaged in establishing schools for expatriates and editing an Italian language newspaper, the Apostolato popolare (The Apostleship of the People). Dickens and other English Liberals of the 1840s admired him immensely, defending him when the Home Office intercepted his mail, and rejoiced in his being called home in 1848 to establish a provisional democratic government in Rome after Giuseppe Garibaldi's military successes. On February 9, 1849, the freedom-fighters proclaimed Rome a republic as the Pope, Pius IX, fled to Gaeta. When Mazzini arrived in Rome, he was immediately appointed a "triumvir" of the new republic on March 29, becoming democratic head of state (as was celebrated in The Illustrated London News). Shortly, however, he was forced to flee Rome for England when papal forces allied with the French army regained control.— Philip V. Allingham]

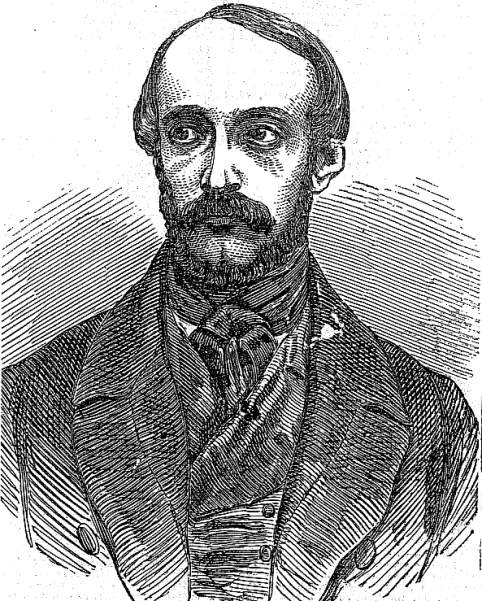

Mazzini, the Roman Triumvir

Portrait of Mazzini from “The Illustrated London News” [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

After the failure of the Savoy expedition, the Swiss Government, unworthily yielding to the demands of Austria and other powers, inhospitably expelled Mazzini from their territory; and it was then that he betook himself to England. Here he resided upwards of thirteen years, always looking forward to the day when Italy should summon her children to her defence. He spent much time and money in carrying on a gratuitous school for the instruction of poor Italians in the metropolis, which was the means of effecting great good. He also wrote several periodicals, English and foreign, on politics, literature, and art.

When the French revolution of February, 1848, broke out, Mazzini conceived that Paris was the proper focus of action, and, accordingly, he went there. He returned to England for a short time, and then Lombardy having risen against the Austrians, he repaired to Milan, where he conducted the paper L'Italia del Popolo. Being persuaded of the faithlessness of Charles Albert, he could not join the King's admirers. He strongly advocated the war; and when Charles Albert turned his back on Milan, and the people, then convinced of his treachery too, wished to make Mazzini dictator, and to entrust the defence of the city to him, the Austrians were already at the gates, and nothing remained for the inhabitants but fight. Mazzini took refuge in the canton of Ticino, in Switzerland thence, shortly after the expedition into the Val d'Intelir, he was again expelled. Rome had now declared itself a republic, and Mazzini was at once elected deputy in the Constituent Assembly for the town of Leghorn [i. e., the port city of Livorno on the Ligurian Sea in western Tuscany], where he landed, and was received with acclamations. After spending some time at Florence, in attempting to effect the fusion of Tuscany and Rome, he at length repaired to Rome. From that moment he has been the leading spirit of the Roman Republic, and is now one of the Triumvirate. Our last accounts present him animating the people to resist the force of General Oudinot.

Mazzini's ideas are conveyed in the motto of the Roman Republic, "Dio et il popolo" ("God and the people"). He is well known to the English public, through a notoriety acquired by Sir James Graham in opening his letters in the English post-office, and communicating their contents to the Austrian Government, which led to the death of the noble-hearted brothers Bandiera [Italian officers in the Austrian army who were collaborating with the nationalists].

Mazzini is of middle height, and extremely thin. There is an unspeakably noble expression in his forehead and eyes. all who were fortunate enough to know him in England, loved him most enthusiastically. [312]

Bibliograaphy

“Mazzini, the Roman Triumvir.” Illustrated London News (19 May 1849): 312.

Last modified 15 July 2010