Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

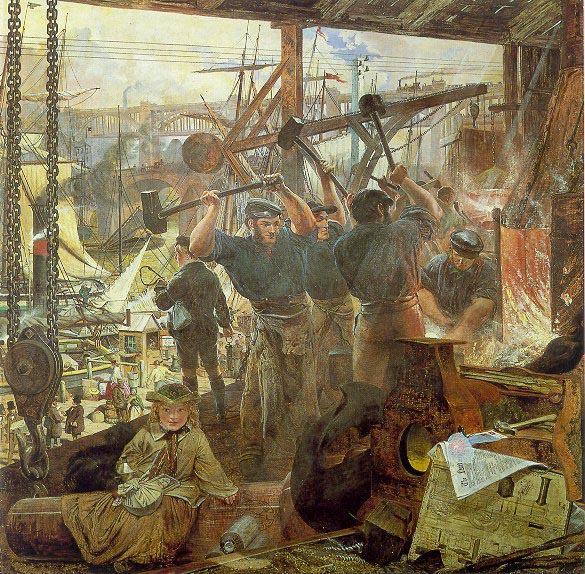

The workman’s status as the mainstay of British industry, which the text of The British Workman emphasized, is also conveyed in the large wood-engravings appearing on the front cover. These images project an heroic version of the working man that forms an interesting parallel with contemporary paintings such as Madox Brown’s Work (1852–56; Manchester City Art Gallery) and William Bell Scott’s Iron and Coal (1862; National Trust).

Left to right: (a) William Bell Scott's Iron and Coal. (b) Ford Madox Brown's Work. (c) [Click on these images and those below to enlarge them.]

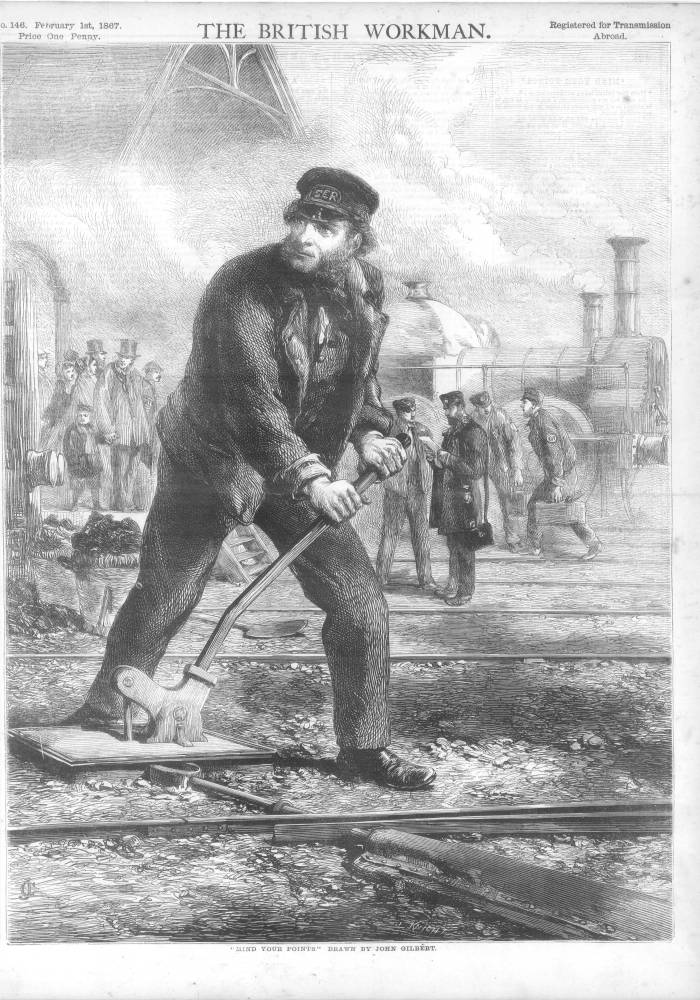

Both paintings celebrate hard work in the form of a muscular determination, a notion of workers as reliable and industrious, heroes of the capitalist and technological age in the manner described by Robinson; and the same orientation is found in a series of designs by Watson, Barnes, Weir and Gilbert. A good example is John Gilbert’s image of ‘Mind your Points’ (The British Workman, no. 146, February 1, 1867).

John Gilbert's Mind your Points.

This is a dynamic composition of an intent figure, changing the railway points as he looks up-line at a train coming into position. At a time when many middle-class travellers were fearful of the carelessness of railway workers (which had led, just two years earlier, to the Staplehurst Disaster (1865), in which Dickens was involved), it is a reassuring assertion of the trustworthiness of the company’s personnel. It is also a direct riposte to Dickens’s own representation of the anxious signalman in the All the Year Round special number of 1866, Mugby Junction. In ‘The Signalman’ the haunted character is fearful that he might fail in his duty and cause an accident; here, by contrast, Gilbert shows us how the dedicated worker is the very embodiment of conscientiousness.

Robert Barnes's The Farmer and Rain.

In Robert Barnes’s ‘The Farmer and the Rain Drops’ (The British Workman, no.223, only dated ‘July 1873’), on the other hand, the artist projects an idea of the sterling qualities of rural workers. The figure is nominally middle-class (being a farmer rather than a farm labourer), but his humble dress is that of the ‘stout yeoman’. This time the emphasis is on careful planning; here, as in Gilbert’s design, the moral message is one of temperance, hard work and fortitude. Like his Biblical counterparts, this farmer takes in the corn before it is ruined by the rain.

Robert Barnes's Snow Track, or the Impressions We Leave Behind Us.

These illustrations condense the Workman’s teachings into monumental designs, and it is interesting to note that Smithies laid a primary emphasis on the quality of the art. The contents consist of sophisticated texts, but the illustrations have an unambiguous directness, an effect, ultimately, like those appearing in an emblem book. The farmer and the railwayman are in this sense types of moral virtues, one embodying scrupulous attention to Duty and the other a model of Prudence and Industry.

This idea of emblematic figures is also applied to representations of middle-class characters. In Barnes’s ‘The Snow Track; Or, the Impressions We Leave Behind’ (The British Workman, no.170, 1 February 1869) the artist depicts a young bourgeois giving money to an elderly beggar. The image is the very embodiment of Dickensian sentimentality, with snow on the ground and privation signalled in the bare trees and cold atmosphere. Thinking of his ‘tracks’, however, the young man is about to give alms; and is thus converted into a type of Charity. Though ‘bold, strong, and very much alive’ (Reid, p. 257), the figure has a deep symbolic resonance.

The images are in each case linked to the stories continuing over the page and function as a sort of portal to the moralising within. Generally, though, they stand alone and it was reported that in some working-class households the front covers were removed and framed, so bringing ‘delight and knowledge into many humble homes’ (Stringer-Rowe, p. 52). As noted earlier, Smithies insisted having a powerful opening image. Though there is no surviving documentation in the form of letters or business records, it is rumoured that he was personally acquainted with ‘his’ artists and engravers, persuading them to do the bold and imposing work that contributed significantly to the magazine’s success, while also (and equally significantly) paying them over the odds.

He was also directly involved in the practicalities of production. He scrutinized the blocks before they went to print, signing the work with his own monogram. This is a sure sign that, as with George Smith of Smith, Elder, every image was subject to the editor’s consideration. The process is enshrined in a series of blocks by Harrison Weir, which have both the artist’s and editor’s signature (Illustrated Books, Original Art-Work & The Pre-Raphaelites, no.115). Like so many Victorian periodicals, The British Workman was a curious mixture of public and private, and can be read as a personal statement functioning in a collaborative system, and directed at a mass audience.

Works Cited

British Workman, The. Ed. J. B. Smithies. London: S. W. Partidge & Co., 1855-92.

Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism.Ed. Laura Brake. Gent: Academia Press, 2009.

Illustrated Books, Original Art-Work & The Pre-Raphaelites. Ian Hodgkins & Co. Ltd, Stroud, 2012.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; New York: Dover, 1975.

Robinson, John. The Social, Mental, and Moral Condition of the British Workman. Blyth: For the Author, 1859.

Stringer-Rowe, G. Thomas Bywater Smithies: A Memoir. London: Woolmer, 1884.

Last modified 29 December 2012