[In creating this Victorian Web version of the article in the 1886 Magazine of Art, I have transcribed the text, following our house style and placed titles of paintings and books in italics rather than between quotation marks, and I have added some of Alma-Tadema's paintings and one by Leighton to the text. The first work illustrated, In My Studio, and the watercolors of the artist's home appear in the original article. — George P. Landow]

hat the Berlin Photographic Company did for the Rembrandts at Cassel and Berlin it has more recently done for Mr. Alma-Tadema, in a volume containing a score and more of photogravures with a sketch of the artist's life by Mr. F. G. Stephens — an album which for taste in production and for quality of its plates has rarely been equalled: a tribute that is an honour at once to the painter and to the publishers. That it is as fine — viewed as a collective example of the process of photogravure — as the Rembrandt achievements can hardly he asserted. The difference, however, is due rather to the difference in the styles and colouring of the old master and the modern inherent defect in the plates themselves. How fine these are may be seen more particularly from that which reproduces one of the most admirable of all the artist's pictures, In My Studio — the picture he presented to Lord Leighton in exchange for the Bath of Psyche, which the President wrought for Mr. Tadema's ante-hall. The work to which I refer is prefaced by Mr. Stephens' essay on Mr. Tadema and his art against which the chief complaint is that it tells us too little of the artist's life. For this reason. I propose to give the story in my own way, based on words from the master's lips, fallen during several conversations.

Left: In My Studio by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Right: Bath of Psyche by Frederic Lord Leighton. Click on images to enlarge them.

Alma-Tadema's position in the World of Art is one apart. Others who have worshipped at the shrine of "Classicism," as it may comprehensively be termed, have, with more or less success, represented ancient life as it may have been; Alma-Tadema convinces us, often in spite of ourselves, that he shows us the life as it was. The George Ebers of the brush — that and a good deal more — he stands proudly on the pedestal he has erected for himself: proudly, yet simply, too — easily and with unaffected bonhomie — fully conscious of his just worth, but entertaining no exaggerated sense either of his own powers or of the public estimation or appreciation. Yet there is hardly a painter in Europe more widely popular than he, whether as an artist or a man. Cosmopolitan in his acquaintance as he has been in his homes, he is essentially a man of many friends: picturesque in gesture and expression, more given to laugh than to frown — yet by no means averse to the latter when he deems there is occasion for it — he possesses little of the phlegmatic calm characteristic of the Dutch. As a matter of fact, he is less a Hollander than a Frieslander, a Parisian, or a Londoner, and his vivacity will be readily understood by the student of the races of the Low Countries. Original in most things and energetic in all, public and private-spirited alike, he is direct, bright, and witty in conversation, as becomes one blessed with a sunny nature: and when he talks in his musical English — in demisemiquavers, as one might say, freely punctuated with minims and crotchets — he startles his hearer continually with refreshing observation, emphasis of opinion, vivid expression, and happy turn of thought. Add to that a familiar knowledge of the world, an intense and absorbing passion for his art, and, in common with so many of the Old Masters, a keen business capacity, set off by a genial courtesy, and the spiritual man is before you.

Three watercolors of Alma-Tadema's home by Herr Waail. Left: The Colonnade. Middle: Mr. Alma-Tadema’s Studio. Right: In the Hall. Click on images to enlarge them.

Surely the house which such a man, successful as he has been, would erect to himself may be imagined with some degree of logical certainty: a dwelling-place like no other on this earth. An original ground-plan, a novel elevation, unheard of arrangements, ornamentation and decoration unprecedented in modern building in point of boldness and chasteness of design and execution, are all combined in this wonderful dwelling. After passing under the colonnade, the visitor may enter by the conservatory, arriving in the antehall, where each of the two-score up right panels of the great screen running round it is painted by a different artist of eminence (most wonderful and beautiful of autograph albums), and where upon the high mantel border are inscribed the hospitable lines:

"I count myself in nothing so happy,

As in a soul rememb'ring my good friends"

Or, he may straightway ascend the brazen staircase and enter the studio: the effect is equally surprising and pleasing.

Three watercolors of Alma-Tadema's home by Herr Waail. Left: The Singing Gallery. Middle: Mrs. Alma-Tadema’s Studio. Right: Entrance to the House from the Garden. Click on images to enlarge them.

The walls of this vast marble-lined chamber, pierced with doors and openings, are decorated with infinite refinement. The surface of the greal apse is covered with silver-leaf in order that the studio may be flooded with pure light, so that the painter's palette may be maintained at painting pitch; and at night the illuminants are reflected from it with brilliant splendour of effect. The celebrated piano in oak, mother-of-pearl, ivory, and I know not what, besides, is raised in well-merited honour in a niche that is lighted by day through windows of onyx. And, greatest marvel of all in a studio, the orthodox, inevitable top-light is for once heterodox, evitable, and absent. The inscriptions about the house, too, are a feature eloquent of the hospitality they proclaim. From the hearty "Salve" above the house-door to the graceful salutation in the ante-hall, from those about the studio to the rest, about the house, they breathe a love of art and a cordial welcome to the visitor. Outside the bed-chamber is a God-keep-you, infinitely comforting, doubtless, to the devout mind: and facing, so that, it may meet the eye if the occupant on his quitting the room in the morning, is a cheery good-morrow that should put him in excellent humour for the day. And the point of it all is that some of the letters are painted in scarlet, which, reckon ing Roman fashion, amount to numbers that mark, literally, red-letter dates in the Alma-Tadema family.

L. Alma-Tadema, R.A. (in the ante-hall). Click on image to enlarge it.

In Dronrijp, near Leeuwarden, in Friesland, Laurence Tadema was born on the 8th January, 1836, the son of a notary in the village. Precocity, the clarion of the great, marked out his future career. At the age of four, so promising was his talent for art, that he received drawing lessons: at five, he corrected his drawing master's work — that is to say, he pointed out faults which his astonished preceptor was forced, with some little mortification, perhaps, to admit. The circumstance was of good omen, for had not Michelangelo as a child corrected the finished drawing of Domenico Ghirlandajo and reduced it, as Vasari says, to a "perfect form". In due time, however, young Tadema was set to follow his father's profession of the law; but he had chanced upon Leonardo da Vinci’s treatise in the village shop, and then upon a book om perspective, and he read them again and again until he knew most, of them by heart. So as he grew up, he formed the determination to become an artist — a resolution which his prudent mother, now at this time widowed, sought in vain to shake, and to which she only yielded when the doctors warned her that her delicate son was fretting himself to death by her opposition to his wishes. With art as the now recognised goal he soon mended, and he applied himself with energy to study, turning his attention principally to the classics. But, as he himself has told me, while hating Latin and Greek for themselves, he loved them for their mythology and archeology, and familiarised himself with their subjects chiefly through the medium of the fancy sketches of gods and god desses and their attributes with which he freely decorated the margins of his school-hooks. He once told me, too, how during a grand school examination, when all the masters sat round in solemn array, just as he was in the middle of a Latin speech, the sun broke in, lighting up the professors' bald heads with liquid gold and touching with fiery light the green curtains that hung beyond. In a moment, all thought of masters, onlookers, and examination vanished — he was stricken dumb with the fine effect of light and shade, until a reproachful prompting voice brought him back unwillingly to earth. Who, I wonder, among all that school assembly suspected the real secret of the boy's astonished silence, or guessed how deep the sunlight ray had struck into his little soul?

Tadema now soon left his native village, and in 1852 became a student under Wappers, "David's antidote." He was a hard-working, rollicking student, always painting throughout the day, never reaching his ideal of good work, and as constantly destroying his pictures, never discouraged, always trying, usually improving. Indeed, with the sole exception of "The trade," all his early works have been burnt by his own hand. Another act, based on sense and expediency not less sound, was the assumption of the " Alma-" which is prefixed to his name; it added grace and euphony to the name, but, what was to better and more practical purpose far, it lifted him in the exhibition catalogues out of the T's and deposited him in the As, near the beginning: an arrangement of especial advantage in the case of foreign catalogues of exhibitions. A typical example, this, of the discernment and sagacity that distinguish him as a shrewd man of the world.

The discovery of some Merovingian antiquities near the village of Dronrijp emphasised and developed young Tadema's taste in mediaeval and classic themes. This pronounced inclination delighted Professor Detaye, the Professor of History of the Antwerp Academy, who, warmed into enthusiasm by so apt a pupil, crammed his young head with archeology of all periods. The youthful painter obtained possession of Gregory of Tours' Historia Francorum and forthwith on suggestions derived from its pages he painted his two principal Merovingian creations — Clotilde at the Tomb of Her Grandchildren and The Education of the Children of Clovis. The last-named was his first great success, for it was bought by the King of the Belgians for the sum of £64, and now hangs in his palace at Brussels. Tadema was by this time in the studio of Baron Leys, after passing under the tutelage of Dyekmans and De Keyser, and was working on some of the master's pictures when he began to turn his attention to Ancient Egypt and to lay the foundation of his reputation as the great apostle of pictorial archaeology of our day throughout the length and breadth of the world of art.

But Alma-Tadema was not content merely to skirt his subject. He entered thoroughly into Ancient Egyptian life, because he knew that upon it was founded all more recent civilisation. At least, it is that which forms a point d'appui for the student of customs; and, as the painter himself loves to express it: “Egypt is the portal to the road which leads through antiquity.” Of this course of study the first important result was An Egyptian Festival Three Thousand Years Ago, for which the then Prince Napoleon bid three thousand francs — "a franc per 'year ago';" but, as four thousand was the artist's price, the offer was declined. In 1862 Mr. Alma-Tadema gained the gold medal at the Antwerp Academy, and in the following year he made his first visit to Italy — an expedition, be it observed, not undertaken till the young painter had firmly marked out the artistic path he determined to follow and had trodden it far enough to know the ground and the direction whither it pointed. I was once talking over this very question of travel with Mr. Alma-Tadema and its proper relative educational value, when he expressed himself emphatically and to the point.

"What is the use," he cried, "of trying to graft a fruit-bearing branch on to a sapling if the sapling has no trunk to speak of to graft it on? Rubens followed the right principle, and, after deriving full benefit from his sojourn abroad, remained Rubens still. But what would he have been if he had undertaken the journey prematurely — before the artist in him was formed?"

Now, at that time Mr. Gambart was the great picture-dealer of the day (il principe Gambarti, as he is still sometimes called in Nice), and he ruled the picture-market in Western Europe beneficently, no doubt, and, not less certainly, with the utmost advantage to himself. When the report circulated in any town which it was his custom to visit on his professional rounds that “Gambart is coming!” plots were forthwith formed by the rising young painters of the community to lure him into their studios to view their works; and bitter was the disappointment when the great man departed straightway after visiting the one or two artists of repute whom he had come to see, and ignored the blandishments that were laid out to ensnare him.

Young Alma-Tadema, who now had a studio of his own, had tasted of the disappointment too: but, through a kindly subterfuge of Leys, who purposely misdirected Gambart's cab-driver to his pupil's studio instead of to another's, he received the yearned-for visitor. When Gambart discovered where he had been deposited, and saw the jolly, smiling young artist at the door, he could not find it in his heart to drive away: so he entered.

“Do you mean to say,” he demanded brusquely, “that you painted that picture?” And he pointed, with obvious surprise, to the Coming out of Church, which stood upon the easel. Mr. Tadema bowed assent.

“Well, then,” he added, after a few words as to price, “let me have twenty-four of the sort, at progressive prices for each half-dozen.”

Here was a stroke of unheard-of luck! And to make matters better, Gambart agreed, after much pleading, that the painter might go back to antiquity instead of to the Middle Ages. Thus it came about that some of the artist's most famous works were included among the pictures which had been ordered, like gloves, at so much per dozen. There was the Three Thousand Years Ago already referred to; then came The Egyptian Chess-Players, with its fund of quiet humour: then The Pyrrhic Dance, a fine work, in which the attitudes of the chief actors were suggested by the figures on an antique vase. It created an extraordinary sensation when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy. Of this picture Mr. Ruskin — a sincere admirer au fond of Mr. Tadema's work — told the Oxford undergraduates once that “the general effect is exactly like a microscopic view of a small detachment of blackbeetles in search of a dead rat;” but, although he added that “it is the last corruption of the Roman State and its Bacchanalian phrenzy which Mr. Alma-Tadema seems to hold it his heavenly mission to pourtray,” he hastened to bear witness to his tremendous ability by declaring that “he differs from all the other artists I have known, except John Lewis, in the gradual increase of technical accuracy which attends and enhances together the expanding range of his dramatic invention; while every year he displays more varied and more complex powers of minute draughtsmanhip, more especially in architectural detail, wherein somewhat priding myself as a speciality, I nevertheless receive continual lessons from him.”

The Roses of Heliogabalus. Sir Laurence Alma Tadema OM RA (1836-1912). 1888. Oil on canvas. 132.7 x 214.4 cm. Pérez Simón Collection, Mexico. Photograph © Studio Sébert reproduced here by kind permission of the Leighton House Museum. Click on image to enlarge it.

So true is this in respect to execution that I may quote, as an example in point, the astonishment of a distinguished Academician, who told me that all the difficult silver-work, marble, and mother-of-pearl, with all their complexity of reflected lights and cross-colourings, in a portion of The Roses of Heliogabalus, were painted in on Varnishing Day at the Royal Academy while the picture was hanging on the wall, and the artist, pipe in mouth, and without model or study of any kind, was keeping up a lively conversation with a little ring of men around him. When I asked him afterwards if this were true, he raised his eyebrows in quiet surprise as he replied, “Why not? It was all thought out before.”

Phidias in the Parthenon and Claudius — the latter so splendidly etched by Rajon — are two more of the pictures painted for Mr. Gambart; and when, after four years of diligent work (that is to say in 1869), they were all completed, the dealer called again. "I want you to paint me twenty-four more," he said, naming prices, on the same progressive principle, but at a much higher rate. The artist agreed, and the first picture delivered was the celebrated Vintage Festival. But, as this was so much more important than any that had gone before, the dealer insisted on paying for it at once at the highest rate. He was a liberal, straightforward man; and the artist tells with generous pleasure how, when at last the second consignment of pictures was finished, Mr. Gambart gave a dinner to the artist-colony of Brussels, Mr. Tadema found himself the honoured guest, and, in front of his cover, a silver jug hearing a flattering inscription, while his napkin concealed a substantial cheque, all over and above the bargain.

It was in this same year of 1869 that Mr. Alma-Tadema came to London and paid this country the greatest compliment in his power by applying for Letters of Denization from the Queen. That proceeding, however, might be called a matter of mere convenience, for not less than a Dutchman or an Englishman, is he an Ancient Greek in spirit — a Conscript Father — a priest of Memphis — just as he pleases. Nor will those who saw him at the “Painters' Masque,” as I did a dozen years or more ago, readily forget how, attired in classic garb, he appeared thoroughly to the manner born: nor repress a smile in recalling how, when the summer dawn was breaking, he threw himself into a hansom cab, pince-nez on nose, cigar in mouth, and his rich but limp and fading flower-wreath drooping at each ear: while the startled market-gardener, wakened on his cart. stared speechless at the strange apparition, and pursued his journey with mouth wide open and bewildered eyes.

His first exhibit on arriving in this country were the pictures he called un Amateur Romain and Un Jongleur, and, partly through their novelty, a remarkable sensation they made. Then followed The Emperor Hadrian Visiting a Romano-British Pottery — a marvel of knowledge, but lacking in grace through the treatment of the figures in the foreground and the strange cutting-off of the labourer's body. This picture the painter ultimately cut up, himself dissatisfied with the general effect, so that the whole picture now makes three, of which the semi-nude slave is the most valuable as a piece of brilliant flesh-painting. In 1875 appeared The Sculpture Gallery, which was really painted — as Gainsborough's Blue Boy was — to combat an idea. It had been said, and steadfastly held, that the satisfactory rendering of sculpture in a picture was impossible. Alma-Tadema set himself to prove the contrary in this work, and succeeded. Ruskin judged of the flesh-painting in it with some severity, for, said he, it belonged to the foreign school by which the shadows were of charcoal and the lights of cream-soap: but while silent on the central purpose of the picture, he admitted it to be the principal historical piece of the year. The large picture was in the collection of the late Mr. Vanderbilt, of New York, and a small replica of the work, I may add, was painted for Mr. Gambart and is now at Nice.

When Mr. Tadema was painting The Picture Gallery archaeological accuracy was hardly of less importance with him than a religion; indeed, the correctness of the accessories in this remarkable work (which, by the way, was painted in response to a challenge) came to tell against the artist, for, as be has himself reminded me, picture-buyers are frequently not picture-lovers, and still less often, antiquity-lovers. Furthermore, Mr. Gambart discovered that an intending purchaser finally refused the picture as "there was so much in it for a fellow to remember, and he did not want to look a fool over it." And again, it is often impossible to be correct on points on which Antiquity is silent: it is so fatally easy to trip. In one of his Eastern pictures, for instance, he introduced a sunflower, in the belief that, as it belonged to the “Jerusalem artichoke” family, it was sure to be right, and he only ascertained ioo late that the sunflower, whether Jerusalem (girasole) or otherwise, is a comparatively modern importation from South America. Then somebody discovered that the shape of the seat in Sappho dated from two hundred years antecedent to Pericles, and another objected that certain Greek lettering on a pedestal ought to have been something else — although the artist had the British Museum at his back as his authority. And, finally, he was cruelly tripped by the discovery that, in one of his Roman flower-pictures he had introduced the Clematis Jackmanni the creation of Mr. Jackman of a very recent date. So Tadema came to the final and obviously correct conclusion that archaeology need be absolutely accurate only in so far as it is pictural and not scientific, and that if it be not expressive or necessary it need not be insisted on.

But Mr. Alma-Tadema's skilful realism has not had the unattainable fortune of convincing every critic, among them Professor Ruskin, who, in his Notes on the Royal Academy for 1875, inveighed against the “gossip of the past,” which is probably agreeable to a supremely ignorant populace. "The actual facts which Shakespeare knew about Rome," he said, "were, in number and accuracy, compared to those which Mr. Alma-Tadema knows, as the pictures of a child's first story-book, compared to Smith's Dictionary of Antiquities. But when Shakespeare wrote —

The noble sister of Publicola,

The Moon of Rome; chaste as the icicle

That's curdled by the frost from purest snow,

And hangs on Dian's temple,

he knew Rome herself to the heart; and Mr. Alma-Tadema, after reading his Smith's Dictionary from A to Z, knows nothing of her but her shadow: and that, cast at sunset." A judgment, this, like so many of Ruskin's, spoilt by exaggeration: yet enclosing a truth that the more sensitive searchers after vibrating life in Mr. Tadema's pictures will assuredly in some measure respond to.

It is not easy to speak of Mr. Tadema's method of work or favourite processes of technique, as he is for ever changing — always trying something else, ever striving to do better. One of the problems he once set himself to solve, and has intermittently returned to, is the relation of the architectural column to the human figure and the juxtaposition of both in a picture without apparent disproportion of size, yet with complete illusion. The reader will have little difficulty in recalling a dozen pictures in which the artist has cunningly endeavoured, with a greater or less measure of success, to give an appearance of truth to the relative size of the column which in reality does not (and within the compass of the canvas could not) belong to it. A Connoissseur is one of the many instances of this. The Convalescent, too, and After the Audience — a picture which was painted for a collector who wanted another Audience at Agrippa's. Then there is Fishing and many more, all with the same motive — the last of them the gorgeous Spring exhibited in 1895 and now in the possession of Herr Robert von Mendelssohn.

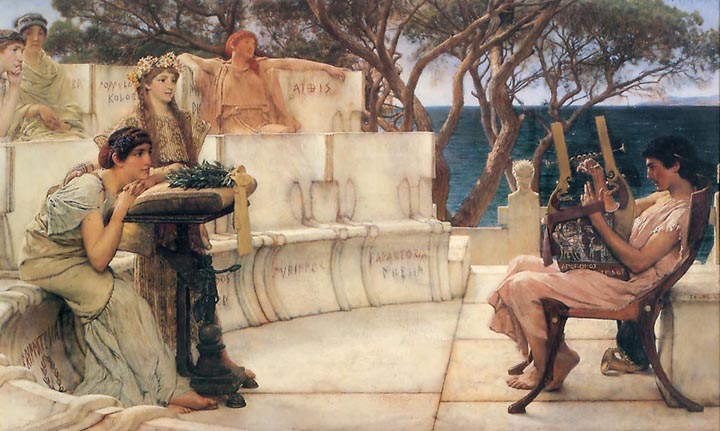

Left: Catullus at Lesbia's. Right: Sappho and Alcaeus. Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore. Click on images to enlarge them.

A curious custom. though logical is this habit of Alma-Tadema's of painting in "classes." Thus there are the “rose pictures” of which I need mention only Catullus at Lesbia’s, Antony and Cleopatra, and Heliogabalus — for the painting of which later work the artist used to receive two boxes of roses a week throughout the winter, each flower being painted from a different model. Then we have the “poppy pictures,” of which of course Tarquinis Superbus, A Hearty Welcome, and The Idyll, or Young Affections are among the chief; the “oleander pictures” and the “circular-seat pictures,” with Sappho, The Improvisatore, and An Old Story, and The Reading from Homer at their head. I may mention that the great work last named (which became a “scratched” picture at the hand of some lunatic vandal at the exhibition) was painted in the six weeks preceding the Academy Sending-In Day, as the picture it replaced — one to have been called Plato — did not satisfy the artist after he had expended eight months of hard work upon it: the same amount of time required for the Heliogabalus itself. This canvas was on an easel in Mr. Tadema's studio the last time I was there, its face turned sorrowfully to the wall, awaiting the fate the painter may ultimately mete out to it. Again, there are the “bridge pictures,” the most important of them By the Bridge, a sort of elaboration of The Flower-Girl; and, finally, there are the three versions of Claudius, of which Ave Cæsar! Iò Saturnalia" (the property of Mrs. Perrins) is the completest and the finest.

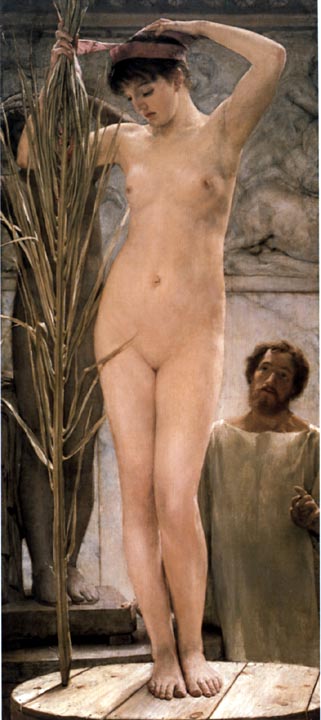

A Sculptor's Model. Click on image to enlarge it.

Like Sir John Millais, Mr. Alma-Tadema has on only one occasion painted a full-length nude female figure. This picture was executed as an object-lesson to his pupil, the Hon. John Collier (its present owner) — the only condition on which he would accept him as a learner. So the youth's father gave the commission, and the son watched the painting whereby it was hoped that he would acquire the difficult art of painting flesh; and the position since taken by Mr. Collier is an interesting commentary on Mr. Alma-Tadema's very practical mode of instruction. For this picture, The Sculptor's Model, the inspiration was drawn from the Esquiline Venus then recently discovered: and the aim of the painter was to realise, as far as possible, the conditions under which the masterpiece was wrought.

I suppose that the leading characteristic of Mr. Alma-Tadema's artistic mind is his conscientiousness. His brilliant Spring was scraped out more than once with its multitude of exquisitely-painted details and lovely heads and figures — as it did not seem to him to "come well" as a whole; so that in its final form it represents the labour of two or three pictures, and comes as near to the intention of its painter as well could be. No part of a canvas is ever scamped or "faked," and Mr. Tadema has told me that the little glimpse of sunny sea and sky in the top corner of many of his pictures often gives him as much trouble as all the rest of the picture. For this conscientiousness and self-application hostile critics in the Press and in his own profession fall foul of him — for where lives an artist who has no such critic among his fellow-workers? “Ça sue!” they exclaim, in the elegant slang of the studio, ignoring the fact that it was by honest sweat that Ter Borch, Gerard Dow, Metsu, De Hoogh, Van Mieris, even Meissonier in our own day, reached the heights of their achievements, and that it is by the same infinite care that Alma-Tadema has risen to his place. Without it, for example, he would never have rivalled and excelled Solomon Ruysdael in his rendering of marble; without it — for he keeps his sudden impulses for his personal intercourse — he would have been nothing. He formed his style with deliberation and care. When he found that be was painting too dark, he re-formed that style as diligently and carefully, hiding no fault to himself nor compounding in anywise with his aesthetic conscience.

“As the sun colours flowers, so art colours life,” runs the motto in his studio; and with the slow deliberation of Nature in her exquisite processes, he follows her and seeks to record her beauties: with so much love, with such keen and delicate appreciation, that those who carp and dub his pictures "pot-boilers" are fain to admit — for they have no other choice — that if so indeed, they are the very apotheoses of "pot-boiling." His originality, his easy confidence and knowledge of effect, the brilliancy of his colour, his juggling with the falsehoods of paint ing so as to make them artistic truths, his scholarship which while always learned is never pedantic, his skill in imitation of textures, his daring which sometimes almost amounts to audacity, and his perfection of finish are a sufficient justification of the pinnacle on which he has been placed. He may not be a poet in the highest sense, but his imagination is at once picturesque and powerful. There may lie “more mechanical steadiness of practice than innate fineness of nerve,” as Ruskin said; his style may to some extent be artificial; indeed, a certain artificiality is inseparable from his style of art. But compare it with the hardness and artificiality of M. Gérôme, and the advantage lying with Mr. Alma-Tadema will be clearly established.

That such a master has attracted imitators in crowds is hardly to be wondered at. I do not mean accidental repeaters of subjects whose treatment is totally different — as when, for example, Mr. Tadema, with An Earthly Paradise himself followed Mr. Orchardson's Master Baby. I remember once calling the artist's attention to an unblushing piece of plagiarism, in which grouping, poses, draperies, and the very folds had all been imitated with slavish accuracy from a work of his own. But Mr. Tadema merely shrugged his shoulders philosophically as he quoted the artistic axiom that “those who follow will never see but the master's back.”

Of Mr. Tadema's honours it is almost unnecessary to speak in detail — for he must possess nearly all the more important that the European Academies have to bestow, and he is, besides, Knight of some half-a-dozen Orders. Of greater value and more permanent delight to him is the knowledge that the character of Aisma, the hero in the art romance of the great Dutch writer Vosmaer, is drawn line for line from him; that a portion of Ebers' Egyptian Princess was suggested by his Flower-Girl; and that a whole prose idyll by the same author was inspired by his Question, of which the title was retained.

Bibliography

Spielmann., M. H. "Laurence Alma-Tadema: A Sketch." Magazine of Art 20 (1886). London: Cassell and Company. Pp. 42-50 and frontispiece. Internet Archive version of a copy in University of Toronto. Web. 31 January 2015.

Created 31 January 2015; proofread and corrected by JB 9 October 2021