This article appeared in the International Studio, Vol. 72 (November 1920-February 1921): 171-7 (see bibliography for more details). It has been formatted for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, with the illustrations as close as possible to their original locations. Note that the initial at the beginning has been added; also, that the self-portrait entitled here The Painter, the portrait of Miss Barbara Horder (The Green Cloak), and the allogorical scene The Worshippers (or Adoration), all appear in the article in black-and-white rather than colour. Page numbers are given in square brackets. [Click on all the images for more information about them].

ILLIAM STRANG is one of the

most interesting living representatives of British Art; and perhaps in certain

respects the most interesting member of

the Royal Academy. His position there

is entirely anomalous: he had only

shown, as he says, a single etching at

Burlington House, and that as long ago

as 1883, when he was elected an Associate

engraver in 1905; and since that date

his principal exhibits have been paintings

in oil. Nevertheless, in this very year

1921, he is made an Engraver Member.

How account for this anomaly?

ILLIAM STRANG is one of the

most interesting living representatives of British Art; and perhaps in certain

respects the most interesting member of

the Royal Academy. His position there

is entirely anomalous: he had only

shown, as he says, a single etching at

Burlington House, and that as long ago

as 1883, when he was elected an Associate

engraver in 1905; and since that date

his principal exhibits have been paintings

in oil. Nevertheless, in this very year

1921, he is made an Engraver Member.

How account for this anomaly?

Portrait of Lucien Pissarro (facing p.171).

William Strang is an Artist. We are rather apt to think that that term indicates not so much a calling as a type of mind; we speak of an "artistic temperament" as connoting a sort of long-haired confusion and a propensity for talking through a broad-brimmed hat. But if there is any real difference between the artistic mind and the rest of humanity it is only this that the artist is concerned above all else with expression. The others have only one predominating craving, viz., to acquire, to attract, to gain, to amass, in other words to take in or unto themselves — and to leave it at that. The artistic minority resemble the others in all respects save one: their constitutional inability to take without and a corresponding desire to give. The majority live by taking, the minority by giving — it is their beatitude. But in all other respects they resemble the rest of humanity, and consequently number in their ranks men of philosophic, scientific, poetic, prosaic, clerkish, mechanical, commercial, dilettantish, methodical, disorderly, or any and every other habit of mind.

To say of Strang, then, that he is an Artist describes really and precisely what he is: a mind primarily concerned with expression. Our brain, however, would seem to be organised on the card-index-system principle, so that we cannot make use of facts or ideas until they have been properly indexed and "filed" in our book of memory. Hence such a bald statement immediately provokes the demand for a "card," a label of some kind, and we are given to experience a feeling of annoyance when such a thing is not readily forthcoming. I am afraid Strang's work has caused a good deal of annoyance to some people on no other account. Strang is not readily rubricised: he is neither an Academicist nor a Classicist, nor a Romanticist; neither an Impressionist nor a Post-Impressionist; he presents himself indeed to the impatient or merely casual observer in Protean illusiveness. Yet Strang is not only a very solid and unevasive personality but a singularly simple and ingenuous one to boot.

In the flesh he is a man of medium height, with iron-gray hair and moustache, a humorously enquiring scrutiny in his steel-gray eyes, a strong Scotch burr in his speech, and an aura of boyish eagerness and infectious enthusiasm about his person. He was born in 1859 at Dumbarton, as the son of a builder. Destined for a business career he became a clerk in the office of a Clyde Shipbuilder. Then it occurred to him to run away to sea. Having thus shown signs of an "artistic temperament," as generally interpreted, along with even less unshakeable evidence of artistic talents he was, on his not long delayed return (the adventure took him no further than Greenock), allowed to go to London and to join there that hot-bed of Genius-culture: the Slade-School, then under — incredible dicta it seems today — Poynter. Strang had three months of Sir Edward and six years of his successor, the never acclimatised but inspiring artist and teacher. Monsieur Alphonse Legros. Legros could speak no English, Strang no French, and yet Strang made extraordinary progress. "Legros," he says, "was the greatest teacher that ever lived, because he was the greatest artist who ever taught." Within a very short time Strang's remarkable talent for drawing and his keen interest in craftsmanship gained him promotion; he became the Professor's assistant in the etching-class.

Then for many years Strang devoted himself to etching, a branch of art in which he has long held a position of unrivalled excellence. Meantime he also painted, but did not exhibit. He presently added to his reputation by a long series of notable portrait-drawings. [171/72]

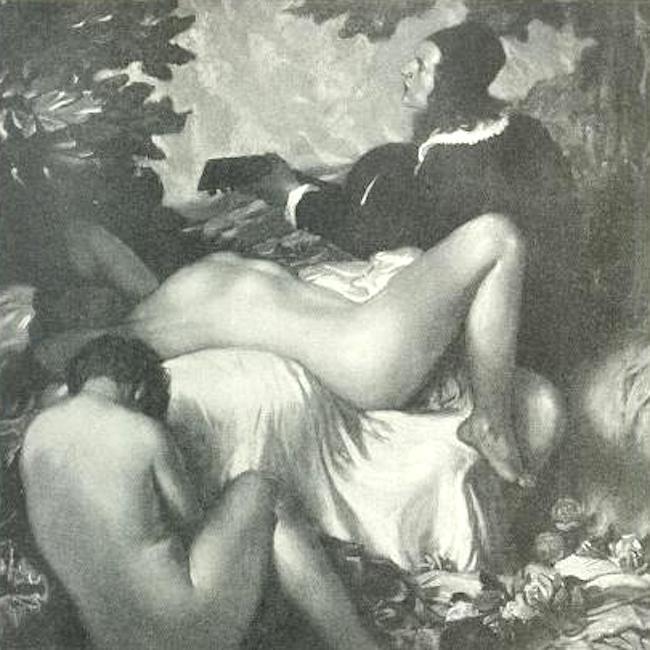

Left: The Painter. Right: The Worshippers.

Strang's etched work now embraces about seven hundred plates; how many hundred drawings he has made, so far, I cannot say, but their number must be very great, thanks to his tremendous energy for work. So for example he went to America for two months, intending to execute a commission of twelve portrait-drawings: he did, in fact, finish forty in that time. How many paintings he has to his credit he himself cannot say, but judging alone by the work he has done in this his sixty-second year his output must be prodigious.

Such are the principal data and demonstrable facts of his life; it is when we come [172/73] to the consideration of his art, the sublimation of his thought on copper, canvas and paper, it is then that the difficulty arises. A constant change of treatment, a variation in style, with elements reminiscent now of this, anon of that "master" or "movement," is characteristic of Strang's whole life-work; and it is precisely this apparent fickleness, this inconstancy that annoys his critics, the more so because everything he touches shows the perfect sureness of the master draughtsman, the deHberateness of the craftsman. It is never a question of a "pale copy" or "feeble imitation," even [172/73] when, as in such a subject as his Danae Rembrandtesque chiaroscuro, or in such a subject as The Love Song (p. 175), Venetian colour-harmony seems to have been the guiding principle. But what is even more intriguing than his inspirations gained from the great old Masters is the collateral production of such pictures as Bal Suzette or The Picnic, which seem to contradict the spirit of these masters in every respect. If an artist believes in harmonious suavity of line and colour, how can he at the same time paint blatant colours and knifeblade contours; or if he is an idealist how can he invent subjects of cynic irony, verging on caricature. Yet the answer is simple.

Strang is an artist; his business is therefore with expression, and the business of expression is twofold, viz., with the thing expressed and with the manner of utterance. As to the manner of utterance, we have already noted the aura of boyish eagerness that, surrounding him still, has clung to him all his life. In every boy the analytic faculty is uppermost. Boy's [173/74] enthusiasms are kindled in the fire of interrogation. They ask not "What is this?" nor "Why is it?", but "How does it work? how is it done?" Strang has never lost this youthful inquisitiveness, this interest in processes. Thus every great picture, every good drawing or etching, awakens in him the desire to investigate its technique, and to emulate it. In this way he has improved upon Holbein's method of drawing and invented a new engraving-tool.

On account of this "inquisitiveness " of Strang's mind much of his work owes its existence quite as often to the manner as to the matter of expression: he is sometimes more interested in how he says a thing, than in the thing itself. On the other hand he is at other times again so interested in the thing he has to say that he is unconscious of the manner in which he says it.

Left: Jairus's Daughter (p. 174). Right: The Love Song (p.175).

When Strang paints or etches imaginative, or what is more often called poetic subjects, things that are remote from actuality, both in form and in content, he breathes and thinks in the atmosphere of "Art"; he is concerned with aesthetic and technical processes. The outstanding achievements of past and present come before his mind, and are therefore reflected in his work. But when he deals with actuality, i.e., with life directly, as when he paints portraits or etches such plates as The Salvation Army or The Socialists, he breathes a different air and thinks in a different manner. If he paints, for example, a young lady in a "Jazz"-hat and a crimson "jumper," the responsibihty for the resulting discord in colour orchestra[174/75]tion is hers, not his; she wore such things, and he does not tamper with such facts. So, too, The Picnic with its dancing couple, time-beating youth and lack of atmospheric modulation, is merely a statement of a series of such facts as happened to interest him at the time, and has no more conscious relation to aesthetic theories or artistic convention than van Eyck's Jan Arnulfini and his Wife in the National Gallery.

The Green Cloak (Miss Barbara Horder).

The absence of impressionistic or plein air doctrines from his art is probably owing to the overpowering early example of his master Legros. He is consequently always more devoted to precise statement of outline and clear rendering of form. "Tone," chiaroscuro, occur in his imaginative subjects, or in portraits such as the John Masefield which was exhibited as The Explorer, but are, generally speaking, absent from his realistic subjects. Moreover, the present brightness, and sometimes harshness of his colour-key, is a [175/76] deliberate device of his, intended to counteract the dimming influence of Time, "the ancient workman" who, in Addison's words, adds such a beautiful brown to the shades, and mellowness to the colours, that he makes every picture appear more perfect than when it came fresh from the master's pencil."

Strang's interest in character has exposed him to the charge of cultivating ugliness, but he can paint beauty in the conventional sense, and even prettiness, when he chooses and when he meets them face to face, of which a number of delightful girl-portraits are witness.

Nevertheless, elegance, chic, verve are things missing in the virile vocabulary of his art. Instead we have disciplined brilliant draughtsmanship, a strange, sometimes sombre, at other times humorous imagination, a high degree of technical skill and — absolute sincerity. It is this sincerity which makes him unorthodox, and therefore disconcerting to those who have persuaded themselves that artistic sincerity means the lifelong retention of one style, one single manner of utterance.

Laughter (p.177).

The position of Strang, the Etcher, is already secure, but unless I am much mistaken, Strang, the Painter, will eventually [176/77] occupy an honoured place along with the Etcher, as one of England's (including Scotland's) outstanding artists, if for no other reason than for his admirable portraiture.

Postscript. — The foregoing article was already in type ready for press when the sad news of Mr. Strang's sudden death arrived. It must stand now as it is, written as if he were still alive and working. He himself doubtless would not have had it otherwise — at all events he wished me to write and knew what I had to say about him — and almost agreed. But I am sensible now how little my article conveys of the many facets of his genius. A poet as well as a painter, he was also perhaps something of a mystic. The Doings of Death (the title of a series of his woodcuts) fascinated him; the subject constantly recurs in his work; and there is that strange etching The Back of the Beyond. I asked him what it meant but he would or could not tell. Quite recently he spoke to me of a "new convention" for portrait-painting he was trying. Always eager, always youthful, always in quest of new ideals, to William Strang life meant work, and Art the Great Adventure.

Bibliography

Furst, Herbert. "The Paintings of William Strang." The International Studio, Vol. 72 (November 1920-February 1921): 171-77. Intenet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 3 August 2020.

Created 3 August 2020