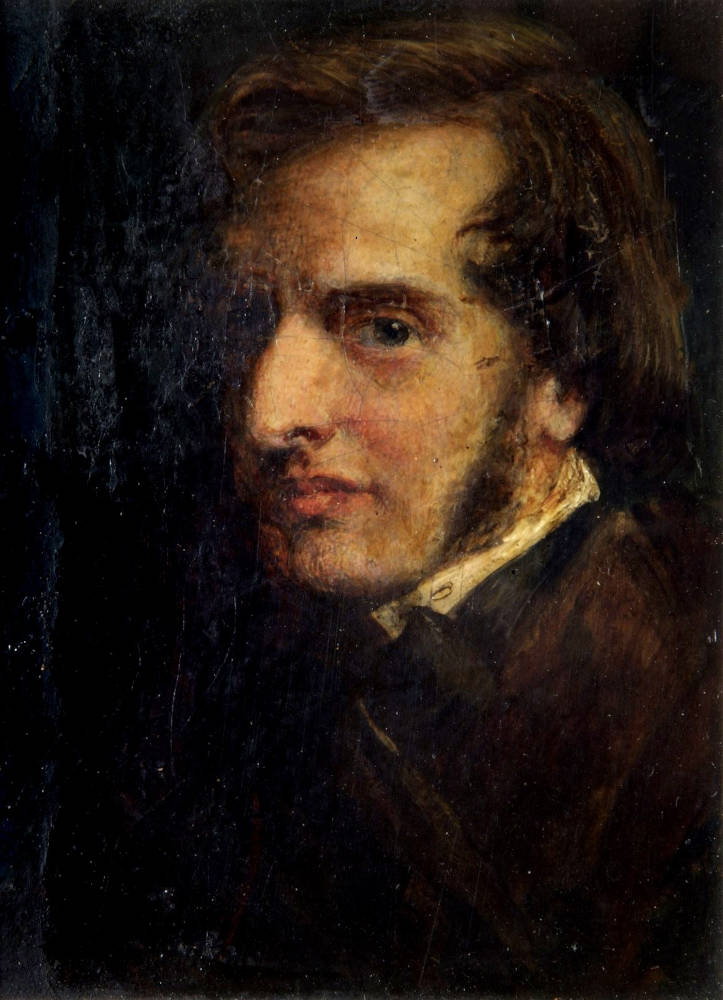

metham was born on September 9, 1821 at Pateley Bridge, Yorkshire, the son of the Reverend James Smetham, a Wesleyan minister. A brother, two uncles, three cousins, and two brothers-in-law were also Wesleyan Methodist ministers or lay preachers. It is therefore not surprising that Smetham was a man of deep religious convictions. By the age of eight James was already drawing and copying art and was determined to become a painter. He received his education at Woodhouse Grove School in Bradford, West Yorkshire, a puritanical boarding school for the sons of Methodist ministers. Its strict and austere curriculum, however, was hardly the place to encourage a pupil with his artistic nature.

On leaving school at age sixteen he was articled to the Gothic Revival architect, Edward James Wilson of Lincoln. Wilson soon recognized that Smetham’s talents were those of an artist and not an architect and Smetham spent much of his time sketching the paintings and sculptures in Lincoln Cathedral. Wilson cancelled his indentures after three years because of Smetham’s long-held desire to become a painter. For the next three years Smetham earned a living painting portraits in Shropshire. The death in 1842 of his elder brother John, whom Smetham idolised, triggered his first major mental crisis, an affliction that would trouble him intermittently throughout his life. Smetham entered the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer in 1843, having previously studied at Cary’s Academy. He failed to be admitted to the R. A. Schools, however, as a full-time student.

After leaving London he again worked as an itinerant portrait painter but the introduction of photography limited his success. The sense of direction his art would take was further dictated by reading the two volumes of John Ruskin’s Modern Painters that had been published in 1849. In the early 1850s Smetham began to exhibit at venues like the Liverpool Academy and the British Institution. He initially exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851. That same year he obtained a teaching post as a drawing master at the Wesleyan Normal College, Westminster, a post he retained for twenty-six years. He apparently only taught one day per week, which left him sufficient time to pursue his own artistic career. In 1854 he married Sarah Goble, a fellow teacher at Wesleyan Normal College who taught music. They would in time have six children. The Smethams initially lived in Pimlico following their marriage. In 1854 Smetham enrolled as a student in F. D. Maurice’s Working Man’s College. It was here that he became acquainted with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Ruskin, two individuals that were to have a great impact on his life. Ruskin was immediately impressed by Smetham’s work.

In 1856 Smetham moved with his family to 1 Park Lane, Paradise Row, Stoke Newington, a village of relative isolation on the northeast outskirts of London. This quiet village proved a conducive setting where he could paint. He was to remain there for the rest of his life except for time spent in mental institutions. Smetham unfortunately never achieved much artistic success. He tried a number of artistic strategies to revive his career, including painting smaller works that he thought he could produce more quickly and sell easier than larger works. He also tried book illustration and producing etchings that he could sell to a subscription list, but these too proved unsuccessful. Smetham was also a poet, essayist, and art critic. He had an article on William Blake published in the January 1869 issue of the Quarterly Review. Because Smetham was a devout Methodist his sense of personal failure and disappointment, coupled with his strong religious beliefs that God would provide for the worldly well-being of the devout, led Smetham to the conclusion that he must truly be a sinner and that God was judging and condemning him. His religious mania, severe depression, and paranoia led to a series of mental breakdowns. He had a serious crisis in 1877 and was confined to Hanwell Insane Asylum in Southall near Ealing. Smetham was mentally ill, delusional, and a recluse for the final twelve years of his life. During his final two years he virtually stopped speaking. He died on February 5, 1889 at Chipping Ongar and was buried in a family grave in Highgate Cemetery, London.

Bibliography

Bishop, Morchard and Edward Malins. James Smetham and Francis Danby. Two 19th Century Romantic Painters. London: Eric & Joan Stevens, 1974.

Casteras, Susan P. James Smetham: Artist, Author, Pre-Raphaelite Associate. Aldershot, U.K.: Scholar Press, 1995.

Davies, William. "Memoir of James Smetham." In Letters of James Smetham. Ed. Sarah Smetham and William Davies. London: Macmillan, 1892. 1-50. Google Books. Free Ebook.

Forsaith, Peter S. “James Smetham, Wesleyan Pre-Raphaelite.” Pre-Raphaelite Society Review 24 (Autumn 2016): 55-65.

Gilchrist, Alexander. The Life of William Blake. Vol. I, London: Macmillan and Co., second edition, 1880.

Grigson, Geoffrey. “James Smetham.” The Cornhill Magazine, 163 (Autumn 1948): 323-46.

Hueffer, Ford M. Ford Madox Brown. A Record of his Life and Works. London: Longmans, Green and Co. 1896.

“James Smetham and C. Allston Collins.” The Art Journal 66 (1904): 281-82.

James Smetham Studio Notebook, 1871-1873. Smetham Collection, SME/1/5/3. The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History. Flickr. Web. 17 April 2021.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Chelsea Years, 1863-67. Ed. William E. Fredeman, Volume 3. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2003.

Rossetti, William Michael. Some Reminiscences of William Michael Rossetti. Volume 2. London: Brown Langham & Co. Ltd., 1906.

Ruskin, John. The Works of John Ruskin. Ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn Vol. 14. London: George Allen, 1904.

Smetham, James. The Letters of James Smetham: With an Introductory Memoir, Ed. Sarah Smetham and William Davies. London: Macmillan, 1892.

Smetham, Sarah: Family Letters and Memoranda, with Some Additional Letters of James Smethan, 2 Vols. Unpublished and undated, Smetham family collection.

Smetham, James. “Modern Sacred Art in England.” The London Review 18 (1862): 51-79.

Created 23 March 2022