This pleasant surprise of a book has as its subject someone who "has largely disappeared from history [although] a celebrity during her lifetime" (7). The American Francesca Alexander belonged to a family which, thanks to inherited wealth, was able to live a life determined by values, interests and beliefs. Thus she and her parents, Bostonians Francis Alexander and Lucia Gray Swett, adopted the Italian city of Florence as their home from home and lived there for half a century enjoying its culture, history, society and climate. Here the Alexanders became a fixture of the anglophone expatriate community, with Francesca soon outshining her artist father in repute. Musacchio's book promises to restore that reputation with a more than capable account of this unusual figure in the cultural landscape of the Victorian period.

As the author states early on, "Francesca Alexander's life cannot be categorized in simple terms" (11). Although her father (1800-80) was a professional artist who became reasonably well regarded in the progressive, liberal city of Boston, his marriage in 1836 to Lucia Swett (1814-1916) combined his idealism with her family fortune (derived from shipping) to allow the couple to remove to Italy in 1853 purely for the enjoyment it would give them. At the same time they maintained over the years a foothold in their home city that kept alive their social standing, connections and finances. In Florence their only child, who had been encouraged from infancy to draw, model and paint, not only developed her artistic abilities but took on a permanent charitable role, which twin pursuits made her well known throughout the city. Anglophone expatriates in Florence already well known such as the Trollopes and the Brownings had no greater cachet as the century progressed than the Alexanders.

As Musacchio says, "She understood her artwork as a duty aligned with her religious faith" (9). The Alexanders, although living in a famously Roman Catholic society, were Protestant, devout Evangelical Christians. This proved no barrier to Francesca's desire for charitable action, although it irked the local clergy from time to time, and she became a widely admired and loved figure of charity amongst the local peasantry or contadini. In contrast with most of their expat peers, the Alexander women mixed with the local working class: as Giuliana Artom Treves, author of The Golden Ring: The Anglo Florentines, 1847-1862, the classic account of these people, has pointed out, the family were not just amongst the first foreigners, but even among the first Italians, to make forays into the villages of the Pistoia Apennine plateau. They made friends among the local people, who then became the usual subjects of Francesca's artwork, in her favoured medium of pen and ink. Often portraits - and in this she was following her father's specialism - these drawings might also use recognisable local individuals as models for religious compositions such as Saint Agnes (1861) and Vision of the Madonna and Child (late 1850s). For the raising of charitable funds, Francesca would also make the portraits of her peers amongst both native Florentines and visiting Britons and Americans (such as Paolina Nardi [1860s] and Emily Russell [1862]).

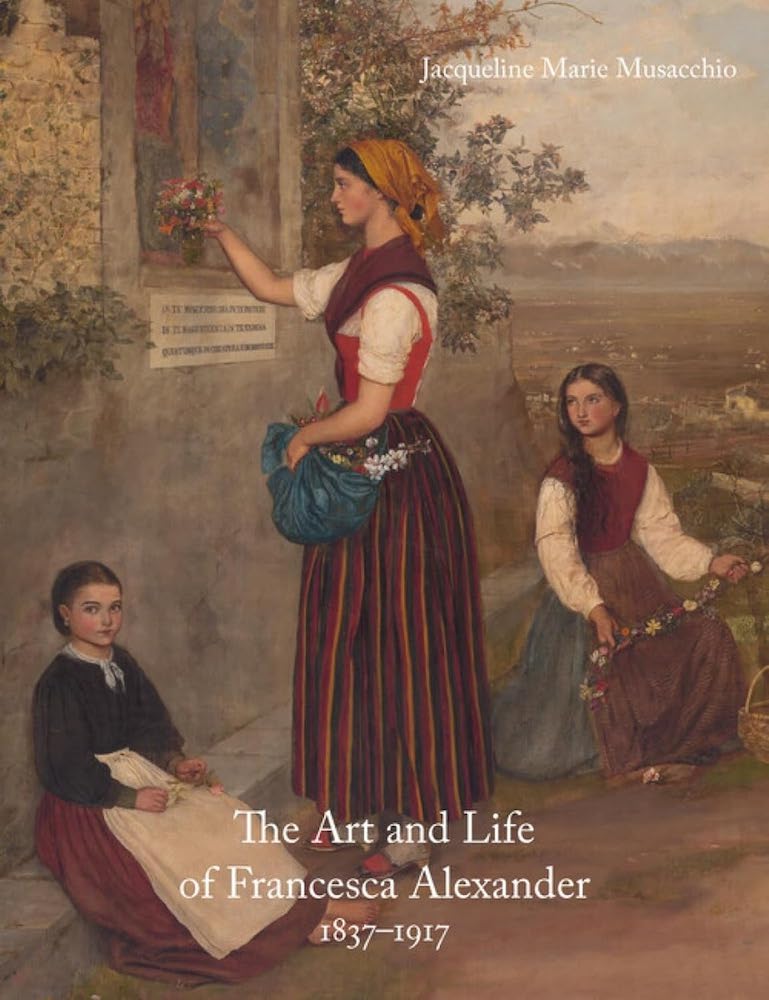

Clorinda, 1865; an oil painting of a local girl.

That Francesca's work was due to her father's early encouragement and her self-imposed programme of learning from copying is apparent in the limitations of her ability to render the human figure and her small range of compositional devices. At the same time, the effectiveness of her apprenticeship can be seen in the advances from the naivety of a Nativity drawn in the late 1850s to the assured arrangement and portraiture of her group portrait Christmas of the early '60s. It was at this time that she produced a handful of paintings (Decorating a Shrine, 1865, appears on the cover of the book, shown above) whose attractiveness make one regret that she did not seek any more rigorous training. In Charity (1861), she approaches the appeal of the equally religious Pre-Raphaelite work of Charles Collins, such as The Devout Childhood of St Elizabeth of Hungary (1852) and The Thoughts with which a Christian Child should be Taught (1852).

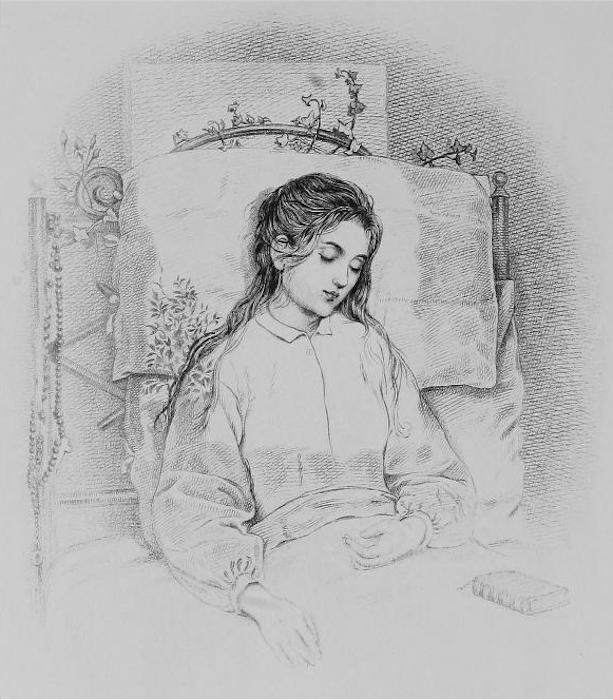

This factor illuminates the later championship of her work by John Ruskin, who in 1882 met Francesca and Lucia (Francis was dead by this time) on what turned out to be his last visit to Florence. His enthusiasm for the artist, her work and her way of life was immediate - as Musacchio observes, "her art effortlessly reflected many of his ideals" (115) - and gave Francesca's work a substantially larger audience and the mother-and-daughter charity a fresh source of revenue. Specifically, he facilitated the publication of the works which remained most familiar to most of those who knew her name, The Story of Ida (1883), the Roadside Songs of Tuscany (1885) (later republished in a preferred version by the artist's mother as Tuscan Songs , 1897), Christ's Folk in the Apennine (1887) and The Hidden Servants (1900). The most famous of these, the Roadside Songs of Tuscany, had 122 folio pages - laborious and minute work that combined calligraphy, nature study and portraiture in her signature sepia pen and ink. Ruskin's imprimatur - Ida, Roadside Songs and Christ's Folk bore his name as editor, and his name was aways used in advertising the books - had a huge effect in both Britain and the United States. Bostonians were especially proud of their "modern saint" (as English journalist Marion Spielmann labelled her): "Everybody is reading it, and it will be reaching and melting human hearts long after the writer shall have joined her beloved friend", wrote the poet John Greenleaf Whittier in 1883 of The Story of Ida. (121).

Left: The Lovers' Parting, a photographic reproduction of Alexander's illustrations for a page in Roadside Songs of Tuscany (p.143). Right: Alexander's frontispiece to The Story of Ida, which Ruskin describes glowingly in his preface to the book. Her narrative and drawing, he says, are both "examples of the purest truth" (vi).

Musacchio has been enabled to produce this book by her connection with the institution that holds most of the primary materials relating to Alexander's life and work, Wellesley College, and she has made diligent and intelligent use of this trove. For instance, she questions what happened to the profits from these fêted publications, turning an appraising eye on Ruskin's championship of this essentially unworldly mother and daughter; and analyses the nature of their privilege as well as both Alexanders' sense of mission, quoting from eye-witnesses whose comments confirm a character that is hard to credit in its unlimited altruism. Although both mother and daughter felt that they eventually became anachronisms - Lucia lived until 1916 and Francesca until the following year - their chosen lifestyle did not waver. As Musacchio points out, as an artist Francesca Alexander "remained outside the art market; while she accepted commissions and sold what she made, she also gave it away or used it as part of a more meaningful exchange" (72), and she shows in this attractive and appealing book that this "life apart" is well worth our attention.

Links to Related Material

- The Brownings in Florence

- Florence in Spring, a painting of 1898 by Matthew Ridley Corbet

- Review of Ben Downing's Queen Bee of Tuscany: The Redoubtable Janet Ross [Review, giving an idea of the vibrant Anglophone community of the time; Ross records Ruskin's admiration of Francesca]

- Florence, a pen and ink drawing of 1907 by Edmund Hort New (1871-1931)

Bibliography

[Book under Review] Musacchio, Jacqueline Marie. The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander, 1837-1917. London: Lund Humphries, 2025. 208 pp. £35.00. ISBN 978-1-84822-636-4

Alexander, Francesca. Christ's Folk in the Apennine. Ed. John Ruskin. Sunnyside, Kent: George Allen, 1887.

_____. The Hidden Servants and other very old Stories. Boston: Little, Brown and co., 1900.

_____. Roadside Songs of Tuscany. Ed. John Ruskin. Sunnyside, Kent: George Allen, 1885.

_____. The Story of Ida. Ed. John Ruskin. Sunnyside, Kent: George Allen, 1883. Internet Archive. Web. 3 July 2025.

_____. Tuscan Songs. Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin and co., 1897.

Treves, Guiliana Artom. The Golden Ring: The Anglo Florentines, 1847-1862. London: Longman Green, 1956.

Created 3 July 2025