The following essay from the Magazine of Art (see bibliography) has the strengths and weaknesses of much Victorian (and perhaps later) magazine criticism of art and literature: it provides useful information about names of dates of Poynter's works, gives an idea of then-standard views of this artist, and offers a theory of the development of his art. Less helpfully, it pontificates on style in art without defining or having much insight into basic terms, and it incorrectly makes Poynter seem much less of an ordinary Victorian painter than his pictures demonstrate him to be. (The decorative initial “A” comes from another issue of the periodical.) — George P. Landow.

volume of "Lectures on Art"— published by Mr. Poynter some three years since — was the most suggestive and interesting book of the kind which has appeared in England during the present generation. Others have written on the same subject with the practised skill of the professional author, and have been aide to put what they have to say into better literary form. We have had volumes full of excellent information — generally second-hand, for England does not shine in the path of art-historical any more than in that of theoretical investigation; and we have had pages signed by great names, in which subjective impressions vividly felt have been set forth with enchanting eloquence. But we have had no works which can be compared with Mr. Poynter's "Lectures" for the width of knowledge and accuracy of observation shown in handling questions connected with practice, and with what I may call the theory of practice. Quite apart, too, from the interest which his volume inspires by the nature and quality of its contents, it deserves the special attention of every student of his work, for the light it throws on his personal predilections, his studies, and his character.

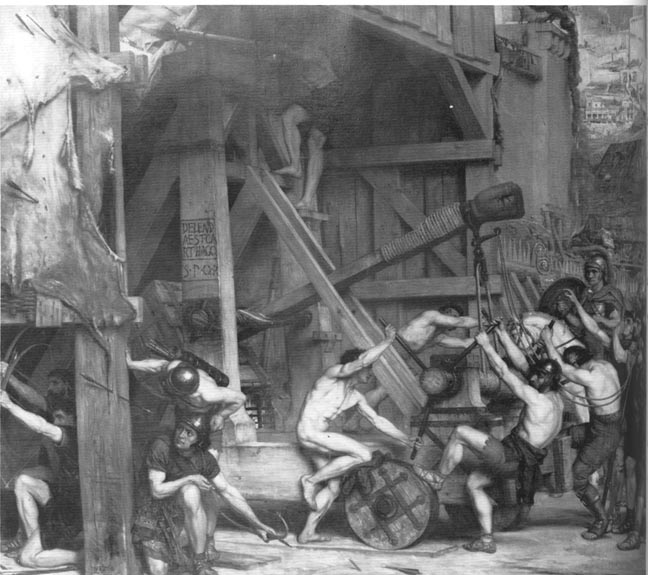

Poynter's The Catapult and the engraving that appeared in the Magazine of Art. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Now Mr. Poynter is essentially a learned painter, and his art demands from those who approach it knowledge at least sufficient to enable them to appreciate the height of his ambition and the nature of his aims. Only those who have themselves passecd through something of the same searching' discipline of mind and hand can expect to find pleasure without an effort in such work as his; but to those who courageously strive to put themselves a point beyond themselves, such an effort will be in itself a reward. An instinctive love of that which is strongest and noblest and most beautiful is not, alas! innate in all of us. Early surroundings will often warp the direction of even a fine natural taste; and there are many amongst us — of whom, by the way, Mr. Poynter himself has said some hard things — who are not sure of what they like, who are not sure of what they think beautiful, but who are haunted by the longing to know and desire only that which is so.

To such as these one might say, "Try to like Mr. Poynter's work. Do not be discouraged by a certain lack of softness and grace, and by the absence of the easy charms which flee before the cruel exigencies of a severe scholarship. Take heart, and try to find out whether he does not give you something which you can be sure of liking, and then he will perhaps lead you to love the works of elder masters whose mighty labours are probably repellent to you in your present state of knowledge and of taste." For the work of a modern painter will always be the more easy to understand merely because he is modern: because, however full and complex his art may be, it is at least nourished from sources open to us all. How much of patient toil and anxious looking must go to the forming of eyes which can enjoy the noble archaisms of an Etruscan vase-painting! It is the gift of a day which is lost to us, and sprang from conditions which our imaginations now vainly strive to reconstruct. But the art which arises in the very hour of our own life can have no secrets which we may not share; and in the present instance we find the less difficulty, since to the secrets of Mr. Poynter's work he himself has furnished the clue.

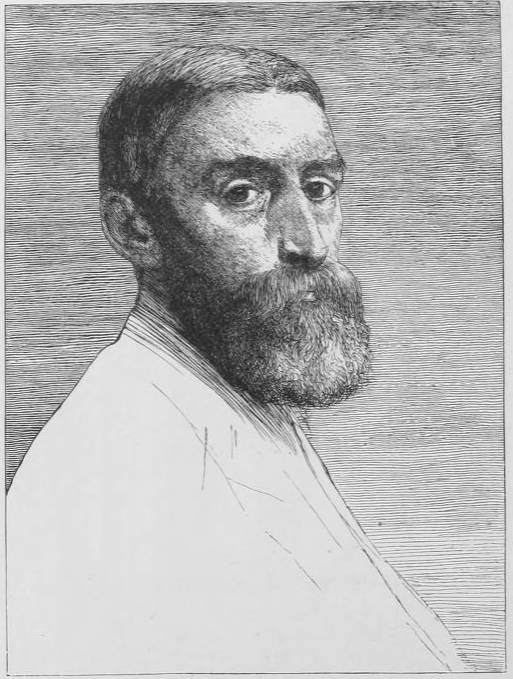

Edward J. Poynter, R. A. — etching by Alphonse Legros. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Every word of his "Lectures on Art" is inspired by a profound study and reverence for the works of Michelangelo, the most heroic master of modern times; and we are thus prepared for the character of Mr. Poynter's art, which is markedly grave and learned rather than spontaneous. Just as the French realist cried out after long looking at his at his model, "Je ne vois plus! la nature me grise," one can imagine Mr. Poynter troubled beyond the power of speech or sight when beholding the walls of that Sistine Chapel whose glories he cherishes with constant passion and worship. Now this passion for and worship of the great Florentine has been shared by men of the most diverse aims and character. Blake adored his spiritual power; Reynolds bowed down before the master in portraiture, who let no shred of individual character escape the keenness of his vision; and François Millet — when he reckoned up the strong sensations received in the magic world which opened itself to him in the galleries of the Louvre — declared that from Michelangelo alone did he obtain "complete impressions." It is because his work is always "complete" that each man who has some serious gift or grace may find himself in Michelangelo; and there is one constant element in all he did which makes his art peculiarly attractive to Mr. Poynter. What we call "style," taken in its abstract sense, is a quality extremely difficult to define; but it is incontestably a marked feature of the art of Michelangelo, as it is, indeed, the indispensable sign of all great art. Every work, of no matter what date, which may claim to be a masterpiece of art, is invariably impregnated with it. Whether we turn to the stupendous achievements of classic times, or to the glories of the Renaissance, we shall always find this distinguishing element; and we shall recognise that it is in virtue of its presence that the slightest sketch or the merest jotting of notes from the hand of a master acquires an untold value.

In England, it is only by an effort of reason and reflection that we arrive at a conception of " style; " neither the public nor those who work for the public have, as a rule, any natural taste for it or any instinctive perception of what it means. Both English artists and their English patrons can and do take unalloyed pleasure in an art which has absolutely no trace of the pre-eminent beauty we call style. This peculiar characteristic has been frequently noted by foreign critics; and they have generally attributed it to the fact that art in England has for centuries hast been divorced from any connection with the development of great religious and politica! institutions. To these it seems to have owed the elevated character which it attained in ancient Greeee and in the Italy of more modern times; and through these the artist himself became an object of interest to the rulers of the State. In England, on the other hand, this divorce is so complete that the State has very naturally seen no reason for occupying itself with the well-being of artists, nor for interfering with the training of a class whom it could not employ. So that artists from whom all official recognition of the national importance of their profession was withheld have been forced to take the chances of such private patronage as they might secure by their own efforts, and in order to win the notice of those from whom alone they could hope to obtain the employment of their powers, they have necessarily been obliged to feel anxiously for each turn of the popular taste. Art thus exists among us only as an object of luxury, and artists turn even to the illustrations which accompany these have been forced, for the most part, into the more or less frivolous office of entertaining the leisure of classes whose occupation is amusement and whose interests are purely personal. In portraiture antl in the painting of anecdotic subjects the English painter finds that his services are chiefly required: in these two branches of his art he displays brilliant, solid, and often original powers, but the grand quality of style is not bis birthright, and such as seek after it are forced to look back for support to the schools of other days and other climes. Thus we constantly find such of the painters of England as are visited by inward promptings which make them ill at ease in the circumstances by which they are surrounded, referring to Michelangelo as to the supreme standard, in relation to which they judge of themselves and of their work, since of all the masters of modern days not one has shown in so large a measure the evidences of nobility of style. Thus, too, one who has, like Mr. Poynter, not only an instinctive love of style, but an inborn desire to see that which is noble, turns naturally to that great spirit which knew nothing that was not noble, and whose every line bears witness to his possession in a transcendent degree of that quality of style denied to lesser men and lesser times.

The desire to see that which is noble is almost necessarily accompanied by some touch of that austerity which comes out very strongly in the portrait of Mr. Poynter which we reproduce from an etching by Legros. For unless one in whom such a desire works is born to exceptional conditions — conditions of which we can now with difficulty conceive — he cannot be satisfied without much conscious putting away of things ignoble, without much painful effort, much of the self-discipline and severity that leave their sign on all it does. And at least until such self-discipline and such rejection of that which is low and trivial have become instinctive by constant habit, the pain of the effort needed will show itself in the manner of all our striving, and will make us seem harsli even when we would be most gracious, so that if we turn even to the illustrations which accompany these pages we shall see at once why Mr. Poynter's work has been rather difficult of access and unattractive to the general public, and also why it is worthy all the honour and attention which the student can bestow.

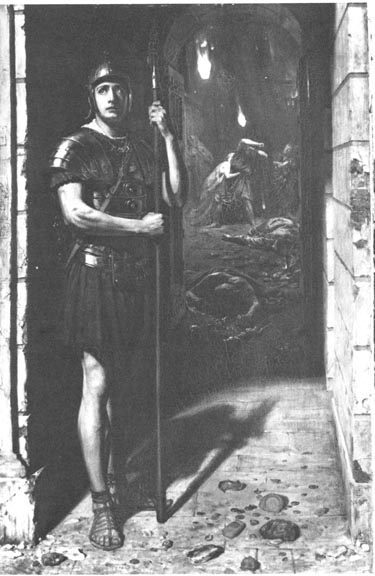

Two of Poynter's paintings mentioned but not reproduced in the Magazine of Art: Faithful unto Death, which Pattison calls The Pompeian Soldier) and Israel in Eygpt . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

From the first works exhibited by Mr. Poynter to the last we may trace an uninterrupted sequence of purpose and achievement. If we run over the list from 1864. — when he made his first appearance on the walls of the Academy with "The Egyptian Sentinel" and "The Siren" — to 1882 — when he exhibited "In the Tepidarium" and "Design for the Decoration of the Dome of St. Paul's" — we find his career marked by great variety of success, sometimes of course even in relative failure; but we have to note, in failure and success alike, the same dominant intention always directed with virile force to the attainment of the same class of objects. "The Egyptian Sentinel" and "The Siren" were followed by "The Pompeian Soldier" (1865), the "Offerings to Isis" (1866), and the "Israel in Egypt" (1867) — a work by which the painter won his first popular triumph, because, as it happened, the subject told a story which interested an enormous audience. For the English public, as I have already said, adores an anecdote or an illustration, and a picture is always popular with them if it vividly presents some already familiar theme — just as a joke to be favourably received by an English meeting cannot be too well worn. Mr. Poynter, therefore, in taking for his subject the Captivity of Israel in Egypt was certain to arouse au outburst of popular sympathy; and his learned presentment of the bondage of the favoured nation under their hard taskmasters not only attracted the attention of all those labouring in the field of Egyptology, but awakened the curiosity of every English household in which the study of the Old Testament was a daily lesson.

But the admiration which his work excited, and which it had deserved liy its intrinsic merits, left the artist apparently unmoved; for the merits which assured him regard and honour in his own profession had very little, if anything, to do with the momentary popularity which he had obtained. Strenuously determined on perfecting his own talent, he chose his next subject simply with a view to the further opportunity which it would afford for testing and developing his powers. He set himself to the painting of "The Catapult" (1868; engraved for this article), with the same unflinching resolution to meet every difficulty of conception or execution full-front which he had shown from the first. The story told by this work — which procured the painter's election as Associate of the Royal Academy — was not, however, likely to arouse much interest in the general public. The fall of Carthage before the brutal energies of Rome was no word of import to English homes, and the suggestions of Mr. Poynter's subject could not carry far with a popular audience; but it proved — and this was why he chose it — a fresh test of his powers. The slaves of Pharaoh appeared in myriad masses cast in strong relief upon their own blue shadows chequered by the glaring sun; the soldiery of Rome were revealed within the giant womb of the monster engine big with the fate of Carthage, their swarthy flesh glowing from out its protecting shades. The complicated details of the vast machine itself were put on canvas with extraordinary precision, and the problems involved in the working out of its construction had evidently been the subject of deliberate calculation. Every groaning pulley and straining rope, every beam and every weight, was adjusted in accordance with the strictest requirements of the engineering science of the past; and it was again made clear that the artist had in him, not only the stuff of an archaeologist, but much of that peculiar mental fibre which lends itself with pleasure to the treatment of mechanical problems — the fibre which has shown itself conspicuously more than once in the history of art, and that in some of her very greatest men. The putting into motion of this old-world battery, with its strangely tormented system of shafts and windlass, needs must give occa- sion to the fullest variety of action among those employed upon it; and so we had groups of the strong servants of Rome, stripped to the sun and wind, toiling with an ennergy which brought up their starting muscles and their splendid thews till the flesh rippled before our eyes like swelling waves beneath the breeze, only with something of a far nobler beauty of playing and changeful line. To the left, in strong contrast, were the harnessed and helmeted archers crouching within the shadows cast by the massive supports of the shed which protected the catapult, and laying shaft to bow in defence of those who worked. The figures of this second group — like those of one or two of the subordinate actors to the right — seemed to show some slackening of the nervous force with which Mr. Poynter had characterised the central personages of his design; and it was remarked by critics that many of the figures were in attitudes of action rather than in action, although less obviously so than was the case in some of his previous works.

Now the power of "drawing movement" would seem, except in very rare instances, to be in some measure denied to men whose main preoccupation is that of attaining high perfection and correctness in draughtsmanship. For, to give the impression of rapid movement, exaggerations always seem to be necessary which are repellent to a steady judgment. Dashes of brilliant suggestion will often render higher service than the most accurate lines of definition, and the very effort to be perfectly accurate will sometimes defeat its own end. Mr. Poynter, dwelling always with great stress of intention on the forms which he seeks to render, does sometimes come short perhaps of producing exactly that impression which he had intended to convey. In this way his "Andromeda and Perseus" (1872) and his "Atalanta's Race" (1876) were disappointing. The thrust from the hand of Perseus, the tarrying of Atalanta, were moments of action which seemed to demand a certain swiftness of vision incompatible possibly with the painter's other gifts. Yet, with charaiteristic deter- mination, he has fastened again and again on some fresh crisis of transitional movement; and in this respect, as in many others, his perfect consistency of aim, strong judgment, and tenacity of purpose have enabled him to snatch victory from every apparent defeat.

St. George and the Dragon and details from The Catapult and Nausicaa and her Maids Playing at Ball. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Let us then — if we would fully realise the advance made by Mr. Poynter in the development of his powers of design — first examine his "St. George and the Dragon," a careful work- manlike drawing executed in glass mosaic for the Central Hall at Westminster in 1870, and then call to mind the impressive scheme for the decoration of the Dome of St. Paul's which figured in the last Academy exhibition. To judge of the progress which he has made in the perfecting of his powers of draughtsmanship, let us look at the constrained attitude (correctly enough reproduced in our illustration for the purposes of this contrast) of the Roman soldier placing his arrow and his bow in the left-hand corner of "The Catapult," and then turn to the running figure of the boy which we have transcribed — with something of the impetuous grace of the original — from "Nausicaa and her Maids Playing at Ball" (1879); or let us study the "Visit to Æsculapius," fitly honoured in 1880 by purchase for the Chantrey Bequest. Or, again — if we would see how much more easily than of old as well as how much more expressively Mr. Poynter now constructs his groups — let us note the arrangement of the soldiers who stand one behind another to the extreme right of "The Catapult," and then observe the two figures of women wringing and washing linen, our second excerpt from the "Nausicaa and her Maids." And, finally, in face of recollections of the dryness and mannerism of some of his earlier portraits, let us place his charming study of the head of a girl — bearing date 1882 — which combines beauty of line and accurate modelling with lovely suggestions of that ineffable quality which gives what the French call "envelope."

Sketch of a head and details from The Catapult and Nausicaa and her Maids Playing at Ball. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Looking and comparing thus, we may learn much in many ways from Mr. Poynter. It is always good to dwell awhile with him: especially for those who are inclined (and there are many such to prize beyond measure the glories of colour, the charms of sentiment, and all such gifts as enhance what we may call the emotional rather than the intellectual pleasures of art. "We cannot but be reminded by his work of the value of certain quite other gifts and qualities which he possesses in a high degree — gifts and qualities which are some of the rarest which can fall to the lot of an artist, and which are especially rare amongst us at the present day. The wide knowledge, the scientific training, which he brings to bear on all he does; the unrelenting tenacity with which he takes a grip of his subject, nor lets it go until he has wrought his will upon it, regardless of all those minor considerations of pretty handling which have first weight with those who in the main desire to please; his great powers as a draughtsman; the spirit and intention which invariably animate his design, may well furnish us with fruitful matter for reflection. And, apart from all the lessons which his art may bring, there are les- sons to be learnt from the character of the arti=st; for no one amongst us now has been more faithful to his gift than he, no one more absolutely consistent in steady purpose, nor more constantly animated by lofty aims.Bibliography

Pattison, Emilia F. S. “Edward J. Poynter, R. A.” Magazine of Art. 6 (November 1882-October 1883): 245-51. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 11 September 2013.

Last modified 10 September 2013