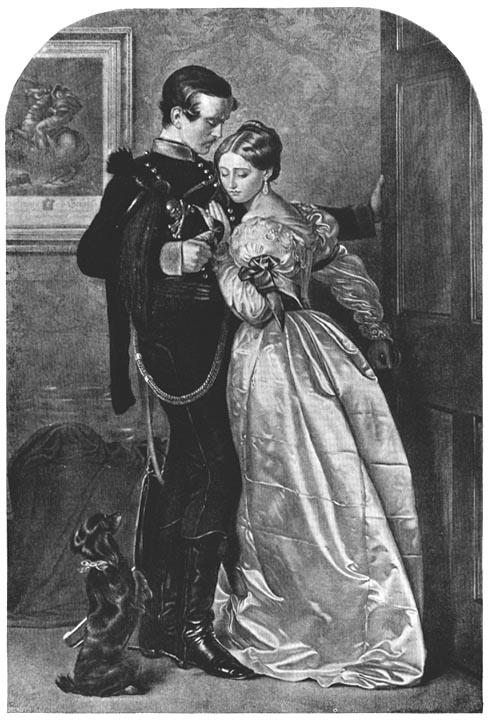

Millais's career struggled in the latter half of the 1850s, marred by a slew of pictures that garnered less income that his previous paintings. In 1859, he decided to produce a what Barlow calls a "commercial Pre-Raphaelite picture" (55) entitled The Black Brunswicker. This image features a scene of contemporary life, a trend started by Hunt and his Awakening Conscience. The painting features a young pair of lovers, the man comforting the woman, their young dog pawing at his owner's leg. According to the artist's son, the scene depicts the departure of a Black Brunswicker on the eve of Quartre Bras, June 1815 from his English lover, who stands strategically between him and the door (Walker Art Gallery, 29).

Millais's inclusion of Jacques-Louis David's painting of militaristic triumph Napoloeon Crossing the St. Bernard Pass lends particular interest to an otherwise artificial scene. This painting, famously commissioned after Napoleon and his army traversed the notoriously treacherous St. Bernard Pass before surprising the Austrians at the Battle of Merengo on June 14, 1808, features the victorious leader posing proudly atop his forceful steed. The painting wreaks of propagandistic lauding, its every detail included to further praise its featured protagonist. With exaggerated diagonals, clean lines, and neither the horse nor Napoleon with a hair out of place, the piece hardly communicates the terror for which the St. Bernard Pass was known. Inscribed on the stone over which the horse stands, is the word Bonaparte, a nod to the triumphant leader.

Millais's choice to feature the scene creates an element of humor in his picture, as the Battle of Quartre-Bras resulted in French victory thanks to Napoleon's military cunning. The painting's presence foreshadows French victory as it mocks the sentimentality of the two figures. Additionally, the artist introduces the theme of the Victorian craze for household goods, and how middle class citizens envisioned their own identities reflected in the material items they possessed. In this way, David's painting represents more than a symbol of materialism, but a victorious ideal to which its owners can aspire.

Both artists depict staged scenes. Napoleon actually rode a mule across the St. Bernard Pass, but requested of David to paint him sitting calmly on his horse. The contrived nature of this image is readily apparent from the static nature of what would have been a more dynamic setting. Napoleon's perfect posture despite a moving animal beneath him, his perfectly draped robe waving upward at an absurdly exaggerated angle, a beam of light singularly illuminating the battle's hero- these are signs of the painting's staged nature. Millais, while he worked from life, produces just as staged a rendering as his predecessor. His models, one a female aristocrat name Kate Dickens, the other a soldier of the 1st Life Guards, posed on separate occasions for the piece, leaning against lay figures in the other's absence (Walker Art Gallery, 45). While this method was hardly unusual for such a painting, it abates the piece's credibility as a convincing representation of an actual occurrence. The melodramatic facial expressions and the manufactured poses of the figures provide visual cues for the viewer as to the staged nature of the scene.

As with his painting Mariana, Millais pays particularly attention to individual objects in this work. While the David print possesses special significance, so does each item of Millais's interior. The wallpaper, a visual theme appearing in more than one of Millais's works, exemplifies the natural motifs typical of William Morris' style. Within the context of The Black Brunswicker, this natural wallpaper can be read as an association with the female being, as nature's beauty was often fused with female beauty in the nineteenth-century mind.

Scanning along the objects in the room, the figures' costumes stand out in their elaborate detail and realistic appearance. Dress was particularly important to Victorians, but in this piece especially, it signifies the roles of each figure. The soldier wears his military costume, appearing especially dapper as he enters the public sphere, and especially clean considering the grit of the battle he is about to face. His dark attire contrasts the comparatively gleaming costume of his partner, shining in white with a bright red ribbon on her sleeve, possibly as homage to her lover at war. The red ribbon theme appears again on the collar of the dog at his owner's feet, subtly conflating the longing beast with the needy woman. The ribbon, as a shared element of their attire, ties them both to the interior domain, the sphere in which they remain as the Brunswicker departs for battle. Millais's attention to material specifics communicates the message of his piece: the predicament of the woman at home as her lover leaves home.

The Black Brunswicker was inspired by earlier pictures of lovers torn apart by circumstance. A Huguenot on St. Batholomew's Day Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roan Catholic Badge, 1851 exemplifies Millais's careful hand and attention to detail. As with the Brunswicker, the Hugeunot must leave his lover's side. Based on Meyerbeer's opera Les Hugeunots, the painting features two lovers, one Protestant, one Catholic, within the factions of sixteenth-century Paris, where tensions escalated to the state-sanctioned massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day in 1572 (Barlow, 39).

The men in both pictures comfort the women they hold, the women differ in stance and attitude. The woman in The Hugeunot looks longingly at her lover, whereas the Brunswicker's lady averts her eyes, instead using her body as a shield between the soldier and the door. The paintings also differ in terms of setting. The Brunswicker and his lover appear indoors, a contrast to the exterior realm the soldier must inevitably face. The pair in The Hugeunotembraces outside, yet despite their embrace outside the confines of an interior, Millais paints nature in a constraining manner. The wall, rendered in high detail, appears uncomfortably close to the couple, the leaves similarly threaten to overpower the scene. These creeping leaves could symbolize the impending separation the couple will experience, approaching steadily yet undetectably. Nature's ominous power figures into other images by Millais, namely, Ophelia, painted in 1852. The natural elements in this composition frame her death scene, creating a claustrophobic sphere from which there appears no escape. The Hugeunot portrays a similar feeling of entrapment, where the enveloping threat of nature reflects the approaching threat of separation.

Related Discussions of Millais by the Same Author

- "Aweary" and Waiting: John Everett Millais's Mariana

- Knowledge and Family in Millais's The Ruling Passion

- Nudes and Knights: Millais's The Knight Errant

- Order in the Family in The Order of Release

Bibliography

Bennett, Mary. Walker Art Gallery. Millais: An Exhibition Organized by the Walker Art Gallery Liverpool and the Royal Academy of Arts London, Jan-Apr 1967. London: Royal Academy, 1967.

Barlow, Paul. Time Present and Time Past: The Art of John Everett Millais. Great Britain: Biddles Ltd, King's Lynn, 2005.

Last modified 15 May 2007