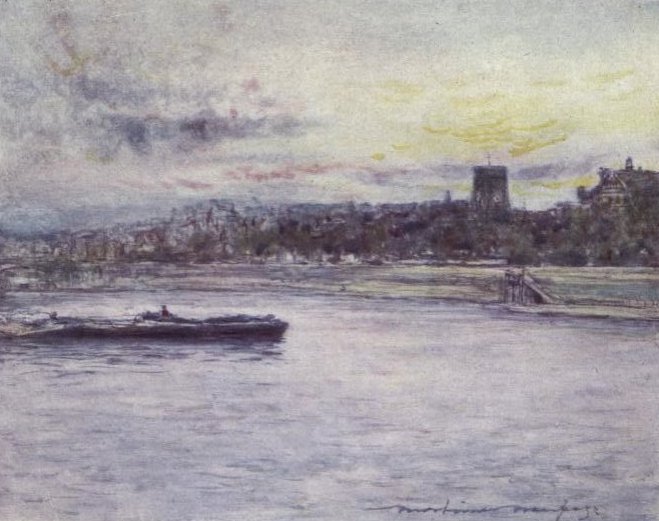

Chelsea Reach with the old church by Mortimer Menpes, R.I.. Watercolor. Source: The Thames, 226. Text and formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the University of Toronto and the Internet Archive and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Chelsea has, perhaps, been more altered by the formation of the Embank- THE RIVER AT LONDON 225 ment than any other part of the river. Its very name implies a bank of shingly beach stretching down to the water, and so it was in old times, and to this beach the gardens of the stately palaces reached. Chelsea has been called a village of palaces. A village it was in old times, quite detached from London, and considered a country residence by many a famous nobleman and states- man. On the site of the row of houses in Cheyne Walk stood the New Manor House built by Henry VIII. as part of the jointure of Catherine Parr, who afterwards lived here with her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour, Lord High Admiral. Both Princess Elizabeth and Lady Jane Grey spent part of their childhood in it. The palace of the Bishops of Winchester, at Southwark, having become dilapidated, as we have seen, a new one was built at Chelsea in 1663, and was occupied by eight successive bishops. Shrewsbury House was another palace built in the reign of Henry VIII. The wife of the Earl of Shrewsbury was the founder of Chatsworth, Oldcotes and Hardwick. In Lawrence or Monmouth House, near the church, lived Smollett the novelist, and further on, somewhere near the end of Beaufort Street, was the house once occupied by Sir Thomas More, whose memory is still cherished in Chelsea. No garden among all the famous gardens of Chelsea was so carefully tended as his. When More had been made Lord Chancellor, and had spent his days hearing cases in the stuffy precincts of the court, how joyfully must he have stepped into his barge in the cool of the evening, to be rowed back up-stream to his roses and his children, where he could indulge his kindly humour and his playfulness, and unbend without fear. Sometimes the royal barge would sweep up after him, and the tyrant Harry himself spring ashore and walk up and down the sweet-scented alleys, with his arm round the Chancellor's neck, a dangerous fondness that in time resulted in More's being cut off altogether from his garden and his peaceful evenings, and in his going down that stream never to return. His monument is in the church, with an inscription written by himself, but whether his body lies here is a question that can never be definitely answered. [225-26]

Related Material

- Chelsea Reach (aquatint by E. L. Laurenson)

- The Power-Station, Chelsea (drawing by G. A. Symington)

- Chelsea Church (1859 engraving)

References

Menpes, Mortimer, R.I., and G[eraldine]. E[dith]. Mitton. The Thames. London: A. & C. Black, 1906. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 18 April 2012.