This article was first published in the Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society, and won First Prize in the John Pickard essay competition. It is reproduced here with the author's permission. — Simon Cooke.

ohn William Waterhouse is one of the most elusive figures in Pre-Raphaelite art. Despite his being called by Christopher Wood ‘the last Pre-Raphaelite artist of real stature’ (148), we are almost entirely left in the dark about much of his personal life, temperament, interests, and opinions. Beyond the fact that he was married to flower artist Esther Kenworthy, and that they supposedly lived an unassuming, quiet, childless life together in North London, we remain unaware of the details of his life, and the nature of the man of whom we speak. Unlike Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, who left a multitude of letters, diaries, and archival material for scholars to feed upon, ‘no letters or diaries survive’ (Wood 148) to paint a first-hand picture of Waterhouse. However, this elusiveness itself could be revealing. By exploring Waterhouse’s undocumented lifestyle, and analysing his impressively vast artistic oeuvre, we can discern that he had obsession with the occult. There is a moderate amount of circumstantial evidence to support Waterhouse’s membership of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Commonly known as the Golden Dawn, this secret Masonic society was the most popular and prominent movement dedicated to the practice of the occult in London in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Certainly, Waterhouse’s artworks are full of images of sorceresses and esoteric symbols, which reveal a knowledge of, and fascination with, occultism far beyond any of his Pre-Raphaelite predecessors or contemporaries. Elizabeth Prettejohn first proposed that Waterhouse’s elusive character could be evidence of a very specific kind of double life: "It is tempting to suggest that the strange dearth of surviving documentation on Waterhouse is evidence of a secret life, perhaps a member of an occult movement, but this must remain pure speculation; since occult movements are by definition secret, they are resistant to research" (30).

Waterhouse critic Peter Trippi has also mentioned ‘Waterhouse’s own occultism’ but acknowledged that due a lack of biographical evidence such a claim must remain ‘in the realm of conjecture’ (‘The Very Victorian Nymphs’). Much of the information regarding occult movements still evades us due to a lack of records and continued secrecy, although some secret societies have become more open to scholarly exploration.

A window appeared through which I could assess the credibility of Prettejohn’s hypothesis in a little more detail. On 11 October 2023, London’s Museum of Freemasonry hosted a Study Day on ‘The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’. This event was the first of its kind and was hosted in conjunction with the University of Surrey. It allowed the public to view archival material relating to the Golden Dawn and speak to experts about the order and its artefacts.

The society, we learn, was largely based in London, though smaller factions existed across the country. Upon accessing the list of over six hundred known members and their addresses, some interesting connections came to light. There would have been far more members than were officially recorded, so the absence of Waterhouse’s name on the list by no means excludes him from potential membership.

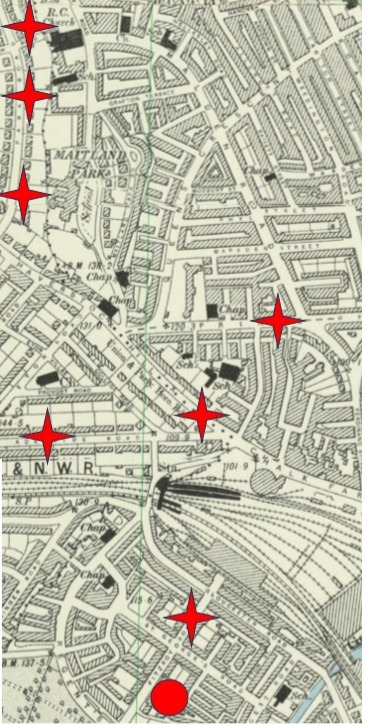

Two maps by Cecilia Rose, based on information provided by the Museum of Freemasonry (London) and National Library of Scotland. Left: Map of Primrose Hill/Chalk Farm, London (1900), showing addresses of John William Waterhouse and Five Members of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (2023). Right: Map of Maida Vale, London (1900), showing addresses of John William Waterhouse and Seven Members of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (2023).

Curiously, fifty-eight of the two hundred recorded London members of the Golden Dawn lived within two miles of one of Waterhouse’s two North London addresses (Primrose Hill Studios, Primrose Hill, where he lived between 1887 and 1900, and 10 Hall Road, Maida Vale, where he spent the remainder of his life). Both Maida Vale and Hampstead hosted a large and close-knit community of Golden Dawn members, and for thirty years between 1887 and his death in 1917, Waterhouse lived right at the centre of it. When Waterhouse lived in Primrose Hill, he had at least seven members residing within a short walk north of his home (the red circle marks Waterhouse’s residence, and the red crosses mark residences of known Golden Dawn members). Upon moving to Maida Vale, Waterhouse found himself within a three-minute walk of at least five Golden Dawn members to the west. This ostensibly strategic position could be merely coincidental, but the fact that he was surrounded by members of the Order suggest that he would at least have known of it – if not have been a part of it himself.

Painting the Occult

Further evidence of some level of involvement in the occult, and potentially the Golden Dawn itself, can be found in his paintings. As Trippi aptly remarks, since we lack his own voice in Waterhouse’s historical footprint, ‘it is only his pictures which remain to speak for him’ (‘John William Waterhouse,’ 123). The Magic Circle (1886) is perhaps his most famous occult work, featuring a sorceress creating a fiery circle in which to carry out a magical ritual. The painting features several ravens: within the Golden Dawn the raven was an occult symbol associated with alchemy and initiations (Regardie 84). However, it seems that the ceremony being carried out here is not alchemical or an initiation rite, but perhaps a ritual in honour of ‘the spirits of the moon,’ undertaken when members of the Golden Dawn progressed to the Grade of Theoricus (when theory was put into practice, ‘Hermetic Order’). We can see the crescent moon sickle in the sorceress’s left hand, whilst her right hand scorches another crescent into the earth. Further symbolic hints to the Hermetic Order can be found in Consulting the Oracle (1884) and Pandora (1896): in both the viewer’s eye is drawn to a subtle inclusion of the rising sun, the official emblem of the Golden Dawn. In Consulting the Oracle, it appears in the form of a mosaic on the marble floor of the temple, centred between the Oracle and the seven onlookers; in Pandora, a humanoid rising sun is engraved onto the side of the box. Both bear a clear resemblance to the spiked, semi-circular symbol replicated on the robes, books and paraphernalia produced and used by the Golden Dawn.

More hints of Golden Dawn sympathies are revealed in the form of the repeated use of the number seven in Waterhouse’s works. Seven is a sacred number beyond any other, both in occultism as a whole and specifically within the Golden Dawn: it represents the seven hitherto identified planets, or seven circles of creativity, which correlate with the seven days of the week. The seven-pointed star, or heptagram, is the Golden Dawn’s emblematic manifestation of this significance, used for several rituals, spells and ceremonies. Unsurprisingly, therefore, in Consulting the Oracle, there are seven spectators, and in The Magic Circle there are seven ravens, though two are obscured by smoke and clothing. However, even in paintings which apparently have no relation to occult subject matter, the number seven recurs: seven sirens surround Ulysses in Ulysses and the Sirens (1891), seven nymphs emerge from the water in Hylas and the Nymphs (1896), and seven figures pose on a picnic blanket for A Tale from the Decameron (1916). It seems that the number seven was embedded in Waterhouse’s subconscious – an unmistakeable betrayal of his preoccupation with the occult.

J. W. Waterhouse’s Ulysses and the Sirens.

J. W. Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs.

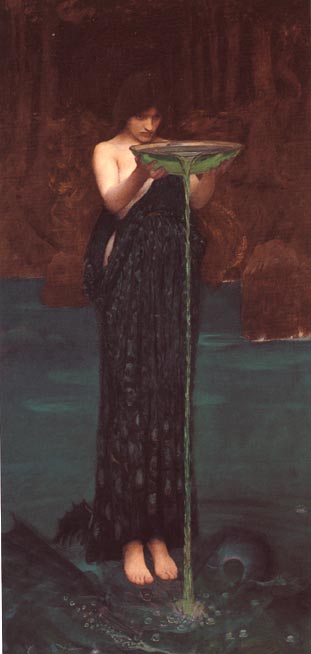

His second recurrent magical fascination seems to be with the sorceress Circe – the formidable seductress of Homer’s Odyssey. As Carole Silver remarks, ‘Waterhouse is almost obsessed with Circe – as a symbol of female power and enchantment – painting her at least four times’ (266). She appears in Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses (1891), Circe Invidiosa (1892), Circe (1907) and The Sorceress (1911), as well as several preparatory sketches - and may also be the basis for the sorceress in The Magic Circle.

Left: J. W. Waterhouse’s Circe offering the Cup to Ulysses; and right: Circe Invidiosa

Reasons for Waterhouse’s focus on one individual could range from a desire to illustrate several aspects of his favourite Greek text, to the influence of powerful female sorceresses in the occult circles in which he may have inhabited. We may never be fully acquainted with his motives, but what is interesting about Waterhouse’s depictions of Circe is that they differ from the mainstream stereotype of the time: Circe was ‘a code word in Victorian journalism for female venality and prostitution’ (Kestner 266), and the same could be said of her in the art world.

Waterhouse’s Circe.

Other Victorian depictions, such as Burne-Jones’s The Wine of Circe (1900) in which Circe poisons the cups of sailors to turn them into swine, or Charles Herman’s Circe (1881) in which she appears to have seduced a dinner guest, present her as a sneaking temptress secretly carrying out an evil deed. She is clothed in a slightly shabby red dress in these works, and in both appearance and behaviour conforms to the conventional prostitute of Victorian fiction.

Burne-Jones’sThe Wine of Circe.

However, in Waterhouse’s Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses and Circe Individiosa she stands tall and proud, clad in revealing but fine garments, commanding the scene as the sole figure and focal point of the image. In the first, and arguably the most famous artistic rendering of Circe, she sits upon a throne, surrounded by items denoting opulence and luxury: though later in the tale she is outwitted by Ulysses, in this instant the sailors she has turned into pigs sit at her feet, and her hand is held high in a manner both impressive and intimidating. It is curious that Waterhouse has chosen to depict Circe’s moments of triumph: though Waterhouse has been criticized in recent scholarship for supposedly misogynistic depictions of evil women as Prettejohn points out, in ‘each of Waterhouse’s presentations, Circe is a powerful sorceress, not a defeated woman […] perhaps [his] women are not so much femme fatales as wise sorceresses, with Circe as their archetype’ (31).

There certainly seems to be an undertone of admiration and respect for Circe embedded in these images – a respect which may stem from witnessing the powerful women of the London occult scene. The Golden Dawn, in particular, had many women at the very top of the Order, due to the fact that men and women were held on an entirely equal plane: in fact, gender was of no significance at all. William Wynn Wescott, who penned the rules to which members agreed upon entering the Order, made it very clear that gender must be entirely disregarded: "Unless while with us you can conceive and act both as a sister and a brother at once, you will become a curse to yourself and a stumbling block unto us. Unless you forget your sex – by the Holy Tetragrammon, I beseech you to be absent" (Owen 109).

His remarkably progressive and alternative approach to gender in the nineteenth century (a period typically seen as enforcing separate spheres for men and women) resulted in strong-minded, assertive, powerful women climbing to positions of authority within the Order with no obstacles. For instance, celebrated medium Moina Mathers was one of the most prominent and senior priestesses, and from 1894 to 1902 the actress Florence Farr became the Chief Adept (or Leader) of the Golden Dawn (see Greer). Most mediums in the Order were actually women because ‘Victorians perceived women to be better mediums than men because of their keen sense of intuition’ (Oberhausen 1) – an attitude that seems to have survived into the present day. Therefore, it is likely that Waterhouse would have seen authoritative women in commanding positions, demonstrating esoteric powers through rituals, seances or magical ceremonies; such experiences would no doubt have influenced his humbled representations of the mighty Circe.

Some Conclusions

I hope to have revealed that, at the very least, Waterhouse had a keen interest in the occult which can be traced through his works, emerging in the mid 1880s and continuing until his death in 1917. However, when considering his extensive knowledge of occult practices and lore as demonstrated in his paintings, his failure to leave any letters or diaries concerning his private life, and his proximity to members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, I believe it likely that he was a member of the Order himself. Involvement in a secret organisation such as this one required discretion, a progressive view on gender equality, and an obsession with occult ritual and empowered female sorceresses, all of which John William Waterhouse possessed.

Bibliography

‘Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the Outer Ritual for 2 – 9 – Grade of Theoricus.’ Stichting Argus [accessed 1 Jan 2024].

Greer, Mary K. Women of the Golden Dawn: Rebels and Priestesses. Vermont: Park Street Press, 1995.

Kestner, Joseph. ‘Before “Ulysses”: Victorian Iconography of the Odysseus Myth,’ James Joyce Quarterly 28, no.3 (1991): 565–594.

Oberhausen, Judy, ‘Sisters in Spirit: Alice Kipling Fleming, Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and 19th-Century Spiritualism,’ British Art Journal 9, no 3 (2009): 38–42.

Owen, Alex. The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2004.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. ‘Waterhouse’s Imagination,’ J. W. Waterhouse: The Modern Pre-Raphaelite. London: Royal Academy, 2010, 23–35.

Regardie, Israel. A Complete Course in Practical, Ceremonial Magic: the Original Account of the Teachings, Rites, and Ceremonies of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications, 2003.

Silver, Carole G. ‘Waterhouse Revisited,’ Victorian Literature and Culture 39, no.1 (2011): 263–269.

Trippi, Peter. ‘John William Waterhouse,’ Pre-Raphaelite and Other Masters: The Andrew Lloyd Collection. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2003.

Trippi, Peter, ‘The Very Victorian nymphs of J. W. Waterhouse,’ Apollo, online edition. 16 Feb 2018, [accessed 1 Jan 2024].

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981.

Created 1 January 2025