Part III (pp. 65-80) of Crastre's book, translated into English by Frederic Taber Cooper, and formatted for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. Page numbers are given in square brackets. All the illustrations come from the same source. Click on them to enlarge them, and for Crastre's full captions.

His Premature End

At this period Bastien-Lepage had already begun to incur the first attacks of the disease which was destined so soon to end his days. He suffered violent pains in the kidneys. He became melancholy, nervous, irritable; he shut himself up in his studio in the Rue Legendre, and even his best friends could not gain admittance. The doc [65/66]tors who were called in recognized the gravity of his illness and ordered energetic treatment and a change of air. The poor artist reconciled himself to go for a time to Brittany, and his choice fell on Concarneau. The keen sea air produced a temporary betterment, and he took advantage of it to work, for he could not resign himself to lay aside his palette and brushes. He spent entire days in a boat and, in spite of his sufferings, executed several landscapes of rare beauty. But his condition, instead of improving, took a turn for the worse. "The digestive tube," he wrote to Theuriet, "is always kicking up a row!" The pain in the kidneys and bowels became at this time so violent that he was forced to decide to return to Paris, in order to consult the men of science once again.

This time, when Dr. Potain examined him, he could no longer deceive himself as to the artist's fate; he saw that his patient was irremediably condemned. However, a sojourn in a milder [66/67] climate might prolong his life for a few months; so he advised Algeria. The prospect of the journey, the desire to make the acquaintance of this land of sunshine which Delacroix, Decamps, and Fromentin had taught him to love, for a few days gave a false strength to the poor sufferer, which produced a deceptive appearance of renewed health and even deceived the artist himself. Besides, Mme. Bastien-Lepage, the "good little mother," was to accompany him, and this unselfish and tender devotion warmed his heart. The poor woman forced back her tears in order to smile upon the unfortunate son whom she knew to be doomed. And so the pitiful pair set forth for the land of sunshine, she consumed with grief, and he almost joyous in the hope of a speedy cure.

His first letters to his friends bore the imprint of good spirits; Algeria aroused his enthusiasm by its clear and vibrant colours; his disease declared a brief truce and he began to form projects. The thought of dying had not yet even [67/68] vaguely occurred to him, though, for that matter, he had no fear of death. The previous year he had painted Gambetta on his Death-bed; and his frequent visits to Ville-d'Avray led him to discuss the inevitable end of life. "I am not afraid of death," he said, "dying is nothing, — the important thing is to survive oneself, and who can be sure of establishing a claim upon posterity? But there! I am talking nonsense! So long as our work is true, nothing else matters."

But before long the ravages of the disease began to make headway; the kidneys no longer performed their function, and he suffered atrocious agonies which stretched him for days at a time on his back. Even the burning heat of the African sun no longer had strength enough to animate his shattered physique; the brush, which the artist from time to time still attempted to take up, fell from between his fingers. He, Bastien-Lepage, painter of the soil, found himself unable to transfer [70/71] to canvas the enchantment of that land of fairy tale! And he poured forth his distress in long and poignant letters, in which could be read in every line the loss of hope and the sure prevision of the now inevitable end.

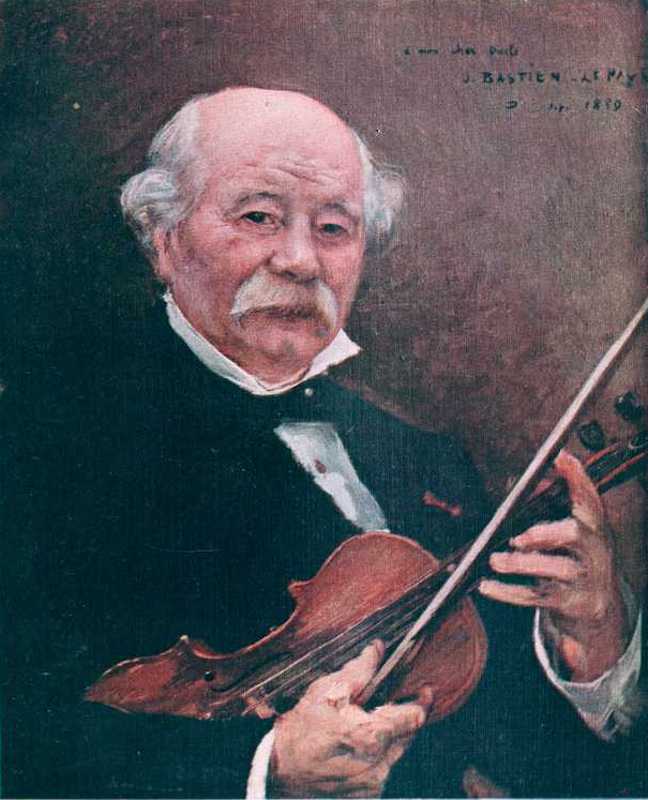

Plate VIII, The Artist's Uncle (following p. 68).

As no amelioration took place, Bastien-Lepage made the return journey to Paris towards the end of May, 1884. He went back to his studio in the Rue Legendre, where he had formerly passed such happy hours in the full enjoyment of a talent at its zenith and a constitution apparently able to defy all tests. Now, however, he dragged around a dying body, with disease gnawing at his vitals. He could no longer sleep without the aid of powerful doses of morphine. The winter-time increased his suffering; his strength rapidly failed him; and, on the tenth of December, at six o'clock in the evening, he drew his last breath, at the age of thirty-six years.As long as he could hold a brush, Bastien-Lepage continued to work, in spite of the sufferings[Pg 72] which racked him. During the year preceding his death, while he was already experiencing frightful tortures, he painted The Woman making Lye and The Little Chimney-sweep, the latter of which is here reproduced. This admirable canvas is to be seen now at the studio of the painter's brother at Neuilly, and forms part of the legacy which M. Émile Bastien-Lepage intends to bequeath to the Louvre. It has never been shown at any Salon, and for that matter there are a good many other paintings and portraits which have never been exhibited in public and which are not for that reason any the less remarkable. We may cite at random: The Portrait of M. É. Bastien-Lepage, The Prince of Wales, Mme. Juliette Drouet, A Little Girl going to School, The Little Pedler asleep, The Vintage, No Help!, The Thames at London, etc.

The very year of his death, shortly before his departure for Algeria, Bastien-Lepage executed a delicious little canvas entitled The Forge, in which [72/73] the artist expended a surprising amount of talent and skill, and which enables us to realize what extraordinary heights his ever progressive genius might have attained, but for the blind and brutal cruelty of Destiny.

His death was a time of mourning for the arts; the regrets which he left behind him were unanimous. Even those who had been opposed to his aesthetic creed paid homage to his great conscientiousness as an artist and his noble character as a man.

During March and April, 1885, only a few months after his death, all literary and artistic Paris flocked to the Hotel de Chimay, an adjunct to the École des Beaux-Arts, where a posthumous exhibition of his works had been organized.

At this exhibition the entire body of his works had been brought together. The museums had loaned the canvases which they possessed and the private collectors had done their share towards the glorification of the artist by entrusting to the [73/74] organizers a goodly number of paintings and portraits which had never figured in any of the Salons.

Thus it was made possible to comprehend at a single glance the life-work of this remarkable artist and to appreciate the distance he had traversed, the progress he had made during his brief existence, and the brilliant prospects that were destroyed by his untimely death.

From all these numerous works, exhibited side by side, what stood out most clearly was the unity of thought which had conceived them and the dogged fidelity to principles which had controlled their execution. At the same time they revealed the amazing adaptability of his talent, which essayed the most diverse and conflicting subjects with the same realistic vigour, bestowing even upon his vaporous and delicate portraits of women a touch which, while light, is unmistakably his own, and in which we recognize that noble, conscientious workmanship, free from all artifice, which [74/75] was the distinctive hall-mark both of his painting and of his character.

But the quality which dominates all the rest in the work of Bastien-Lepage, and which emanates from it like the fragrance which is exhaled by certain precious essences, is his ardent and deep-rooted love for his native soil. This form of local patriotism, determined by the boundaries of Lorraine, underwent a noble expansion to the point of encircling the entire earth; for while the painter chose his models out of the familiar landscape of his childhood's home, his observation and his art broke out of the bounds of this special setting and embraced rustic humanity throughout France and even beyond. His peasants are unmistakably from the banks of the Meuse in type and in customs, but they are from the world at large in gesture and in philosophy of life. Whether he comes from the North or from the South, the tiller of the soil wages the same conflict with ungrateful furrows, the spade and the plough [75-76] imprint the same calluses on his bony hands, the sun browns his energetic and stubborn features to the same deep tan. It is in this respect that the art of Bastien-Lepage assumes a higher significance; like Millet, it is not a peasant whom he paints, but the peasant, forever unchanging in spite of latitude. But if his work has attained this higher eminence of generalization, it is precisely for the reason that the artist's watchful eye has succeeded in discovering, in the life of the peasantry, that state of mind which is common to them all, that immutable gesture which they have always made and always will make. He has understood and translated with inspired eloquence their rugged strength, their naïve awkwardness, their simple intelligence.

Another glorious distinction of Bastien-Lepage was that he loved the fields as well as he loved the peasants. Not fields drowned beneath melancholy shadow and pallid shifting light, but fields bathed in sunshine, until the golden tassels of the grain [76/77] crackle like sparks under the fire of the midday sun. Always and everywhere he sought for light, and in the midst of it his modest protagonists of rustic life stand out in all their vigour.

It would be easy to cite, among our best contemporary painters, a considerable number of artists who are brilliantly continuing the tradition left by Bastien-Lepage and emulating his predilection for the luminous brilliance of the open air. How often, in the presence of a canvas by Lhermitte, our thoughts go back to the painter of Lorraine, whose vigorous execution and joyous colouring seem to have been reincarnated! Art is indebted to Bastien-Lepage for having reinstated nature in all her literal truth by proving that, in order to be beautiful, she has no need of artificial and superfluous adornment.

Lorraine, out of gratitude, wished to perpetuate the memory of this glorious son of the Meuse, who had so eloquently celebrated the vitality and poetry of his natal earth. It was at Damvillers [77/78] itself that it was decided to raise a monument to the great painter; and around its pedestal there were gathered the "good little mother," all in tears, the assembled population of the village and the whole region round about, and even the Government took part in the pious ceremony by sending as its representative M. Gustave Larroumet, director of the Beaux-Arts. This eloquent art critic brought as a tribute to the departed painter the official seal of immortality, and he pronounced it in terms vibrant with emotion.

"At the moment," he said, "when ordinarily the best of artists have done no more than to give indications of their originality and when ripening years alone begin to keep the promises of youth, Jules Bastien-Lepage died, leaving masterpieces behind him, besides having liberated an artistic formula from the tendencies and exaggerations which hampered it, and indicated to the art of painting a new pathway along which his young [78/79] heirs are advancing with an assured step. He loved nature and truth; he loved his own people, and no one ever lived who was surrounded with a greater degree of affection; he inspired faithful friendships which he himself enjoyed to the full; and those whom he left behind soothe their heart-ache with the balm of tender memories; he practised his art without ever making sacrifice to passing fashion or sordid profit; there was no place in his mind or in his heart for any other than noble and generous thoughts. Let us comfort ourselves, therefore, for what his death has taken from us by the thought of what his life has left to us, and let us assign him his place in the ranks of the younger master painters who have been mown down in full flower, close beside that of Géricault and of Henri Regnault."

In his admirable biographic and critical study of Bastien-Lepage, whose personal friend he had been, M. L. de Fourcaud, by way of conclusion, bids him this touching farewell:[79-80]

"Poor Bastien-Lepage, snatched away one winter's night, at thirty-six years of age, in the fairest flowering of his bright promise, in the richest expansion of his personality; may each returning month of May bring at least an abundance of blossoms to the apple tree beside his grave! For the blossoms of the apple were always, in his eyes, so fair a sight!"

To-day he sleeps forever in a corner of that Lorraine land which he loved so dearly, and perhaps in the cemetery of his native village his shade can still hear the familiar accents of his native dialect. The great painter of Lorraine could never have slept his eternal sleep in any other soil than that.

Painter of flowers, painter of nature, painter of the earth which is forever deathless and forever renewed, Bastien-Lepage has chosen that better part; his work will live as long as these, his models, and will go down through the centuries in all the splendour of increasing beauty and eternal youth.

Related Material

Bibliography

Crastre, François. Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884). Frederick A. Stokes, 1914. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 12 March 2020.

Created 12 March 2020