This essay is reprinted, with minor editorial changes, and the addition of links, from The PRS Review, Special Issue in celebration of Ford Madox Brown's centenary (2021). The essay is reproduced with permission of the author and editor. — Simon Cooke

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG) has the largest collection of prints, drawings and watercolours by Ford Madox Brown (1821–92). Almost a third of these are preparatory studies for two major history paintings depicting England’s medieval past: Chaucer at the Court of Edward III and Wycliffe reading his Translation of the Bible to John of Gaunt. By focusing on his works on paper it is possible to gain a far greater insight into his approach to history than is possible through looking at his paintings alone. This essay will use BMAG’s works on paper to explore both Brown’s approach as a history painter and how artists responded to the changes in the nature of historiography that occurred in the nineteenth century.

Ford Madox Brown, Chaucer at the Court of Edward III, 1851. The Tate Gallery, London.

The BMAG collection gives us a unique insight into Brown’s working process from conception to completion. A sheet of drawings filled with pencil sketches of Alfred the Great throws light on his initial steps in selecting a subject. Over the top of the sketches he has written a list of famous historical figures such as Geoffrey Chaucer, Edward III and the Black Prince, and key dates relating to them. From his diary we know that Brown often used history books as inspiration early in his career to find the subjects of his paintings. In his first entry he recalls that:

In the summer of [18]45 I went to the British Museum to read Sir James Mackintosh’s History of England, having heard that it was of a phylosophical [sic] nature, with a view to select some subject connected with the history of this Country of a general and comprehensive nature … Glancing over the pages of the above named history I fell upon a passage to this effect as near as I can remember ‘And it is scarcely to be wondered at, that English about this period should have become the judicial language of the country, ennobled as it had recently been by the genius of Geoffrey Chaucer.’ This at one fixed me, I immediately saw visions of Chaucer reading his poems to knights & Ladyes fair, the king & court amid air and sun shine. [Diary 1–2]

Having found a suitable subject Brown was keen to check that his vision could realistically have taken place. These notes are likely to have been made during that process and this is backed up by his diary in which he recounted:

When I arrived at Rome, from the library of the English Academy I procured the works and life of our first poet and fortunately I found that the facts known respecting him perfectly admitted of the idea I had already conceived of the subject to wit, Chaucer reading his poëms [sic] to Edward the 3rd & his court bringing in other noted characters such as the black prince etc. [Diary 2]

With a subject identified Brown felt it was necessary for any history painter to 'consult the proper authorities for his costume, and such objects as may fill his canvas; as the architecture, furniture, vegetation or landscape, or accessories, necessary to the elucidation of the subject' (‘On the Mechanism of a Historical Picture’ 3).

The sale catalogue of Brown’s household contents shows that he owned Fairholt’s Costume in England, and Thomas Hope’s Costume of the Ancients (Catalogue of the Household 18). The same catalogue and letters from Dante Rossetti dated 1861 reveals that Brown also owned at least one volume of Knight’s Pictorial History of England, first published in four volumes between 1837 and 1841 (Catalogue 18). On 1 December Rossetti wrote ‘Dear Brown, I’m doing the Parable of the Vineyard for the shop glass. I think you have a number of Pictorial History of England with a Saxon winepress in it. Would you kindly send it me by book post?’ (Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti 2: 426). Two days later he sent another note saying: ‘Dear Brown, Many thanks for the Pict. Hist'’ (427). Although Rossetti was writing in 1861 it is likely that his friend was using this popular sourcebook as early as the 1840s as a number of figures from his painting Chaucer appear to be based on its illustrations.

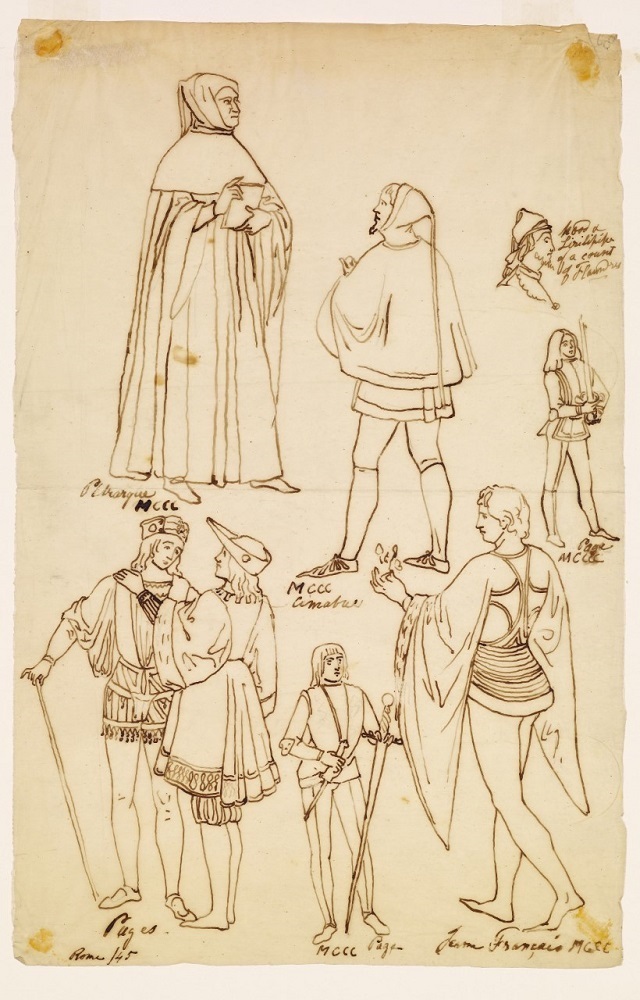

Some sheets of costume studies on tracing paper at the BMAG show what use Brown made of historical sourcebooks to research the clothing of his figures. They are studies of medieval costumes and show this next step in Brown’s working process where he would trace or draw illustrations from sourcebooks. In the late 1970s Roger Smith indentified the drawings as copies of illustrations from an early nineteenth century costume sourcebook called Costume Historique by Camille Bonnard.

Some examples of Madox Brown’s detailed preparatory work, in the Birmingham collection. Left: A sheet of costume studies, and right: a study of a man wearing a medieval hood.

In the mid-nineteenth century Costume Historique was known as one of the best sources for artists and costume designers. The Art Union gave it high praise believing that the research behind it, and the information it provided, surpassed similar British works, such as the numerous volumes published by Joseph Strutt (1749–1802), Sir Samuel Meyrick’s Critical Inquiry into ancient Armour (1824) and Charles Stothard’s Monumental Effigies of Great Britain (1817). Brown may well have been introduced to the book through his friendship with Edward Armitage (1817–96) in Paris. Armitage joined the atelier of Paul Delaroche (1797–1856) and worked with his master on the grand scheme of the Hemicycle at the École des Beaux-Arts (1841). Several of the figures in the Hemicycle appear to have been taken from Costume Historique including Petrarch and the figure on the far left in striped hose. The high level of finish and detail found in the book meant that it also had a strong reputation among artists working in England, particularly the Pre-Raphaelites. Smith surmises that the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were introduced to the book by Brown (29). It was certainly popular with the Brotherhood and their associates. Several of their works include figures in costumes taken from Costume Historique, notably John Everett Millais’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil(1848–9, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool), and around 1849 Rossetti bought a black and white copy. The book was hugely expensive and it seems as if most artists, like Brown, relied on copies in libraries in institutions such as the English Academy in Rome, the British Museum and the Royal Academy (Smith 30).

However, Smith overlooked the fact that not all the drawings were copied from Costume Historique. Identifying the head in top right of one of the sheets has revealed that he is likely to have copied it from J. R. Planché's British Costume: A Complete History of the Dress of the Inhabitants of the British Isles (1834). Planché was one of the first costume historians and published several illustrated books on the subject. It is clear that Brown was not just copying the pictures but digesting the text too. In the book Planché gives the illustration the title ‘Charles le Bon, Count of Flanders’ and on the same page explains to his readers that during Edward III’s reign the fashion was for ‘short hoods and liripipes (the long tails or tippets of the hoods)’. Brown notes the title next to his drawing but has problems with the spelling calling it a ‘hood and lirilipipe [sic] of a count of Flanders’. His drawing became the blue-print for a hood that he made up. On 25 September 1847 he wrote in his diary ‘fumbled till 12 o'clock over the Hood of the left hand corner figure of the "knight" made a lirlipipe [sic] for it' (Diary 7). A black chalk drawing of a figure wearing the hood dated 1847, in the Birmingham collection reveals that he later arranged it on a lay figure and drew a study from it for the man fourth up on the left hand side of Chaucer. From the two drawings and the diary entry it is possible to get a very clear idea of his working process and the way in which he used the increasing number of historical sourcebooks being published. In the final version of the painting the hood is used twice showing his efficiency in using the props that he had made up. From other drawings in the collection we know that he made up other garments too, including a jester’s hood and a cardinal’s robe. He mentions several excursions to buy fabric such as a ‘germon [sic] velvet’ he bought at a ‘bargain’ price for Chaucer’s robes on 14 October in 1847 (Diary 10). He spent a huge amount of time arranging the fabric on lay figures – his diary records that he spent hours getting the folds exactly as he wanted them before making carefully observed drapery studies. These studies in combination with his nude studies from professional models, and minute studies of various body parts, show how closely he stuck to the method he was taught at art school for producing history paintings, allowing him to make sure that the figures in the much larger painting would be convincing and accurate.

Historiography

As well as giving a much more rounded insight into Brown's working process these drawings reveal the changes to historiography which had taken place in the first half of the nineteenth century. During this period there was a rise in the popularity of history and changes in what was perceived of as history. This was partly due to the significant social upheavals which had occurred during the Industrial Revolution. The huge migration from the countryside to the city and the social unrest this caused led to a sense of nostalgia for the past. A new middle-class readership emerged who had not had a classical education. These readers wanted to know about the past, but not the classical past; they wanted to know about more recent British history. Historians, novelists and publishers responded to their new readership. Walter Scott began writing historical novels which brought history to life for his readers by blending historical facts with successful narratives. This spawned a whole new genre of novels which were entertaining and educational and could be read by the whole family. Although Scott included well-known figures from history in his books, his characters were often drawn from the common people. This is a particular trend of mid-nineteenth century history which began to look not just at great leaders but also at the lives of everyday people.

History books themselves changed. Rather than just discussing great historical events and battles they began to look at the lives of ordinary people as well. New historical disciplines were formed such as the History of Dress and great emphasis was placed on historical accuracy which meant using artefacts such as medieval illuminated manuscripts for sources of costume, furniture and details of everyday life. This in itself made history more visual, and publishers such as Charles Knight began producing books full of illustrations. These changes heavily affected art as can be seen from the preparatory drawings by Brown at BMAG. Nineteenth-century artists were expected to produce works of art from British history rather than using scenes from mythology and the classical past which had most often featured in previous history paintings. They also sought to include the ordinary man where possible. Brown chose to depict famous characters from the past but in both Chaucer at the Court of Edward III and Wycliffe Reading the Bible he created multi-figured scenes to include the more lowly such as page boys, musicians and servants, to show a wide variety of classes requiring a high level of research.

As Brown's notes show, artists had to become researchers and had to use the latest sources to be as historically accurate as possible in their scenes from British history. In the introduction to Specimens of Ancient Furniture (1836) Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick advised that

Extreme accuracy, even in the minutest detail, can alone produce that illusion which is requisite for the perfect success of a work of art; … an anachronism in an historical picture is as offensive to the eye of taste as is an imperfect metaphor or a defective verse to the ear. [Shaw 2]

To aid them in their search for historical accuracy sourcebooks such as Costume Historique and Specimens of Ancient Furniture were produced. As we have seen, several of the drawings at BMAG are of costumes but others reveal architectural details which Brown copied from sourcebooks. On 30 November 1847 he used the British Museum as a resource for Wycliffe and wrote in his diary: ‘Went out to see about the [British] Museum for consulting authorities … went to the reading room of Museum, saw Levis’s life of Wycliff, Southey’s book of the church. Met Lucy there in search of documents for his landing of Puritans in New Plymouth’ (Diary 17). As this extract shows, Brown was not alone in consulting books and documents in order to make his paintings historically accurate. Like much of his diary this illuminating passage suggests that undertaking such research was standard practice for a history painter working in England in the nineteenth century. Not only was the research necessary to create a convincing scene but it also added a greater intellectual element to painting, an idea artists had been careful to stress since the Renaissance in order to differentiate themselves from artisans.

In the same week, Brown visited print shops and the National Gallery before returning to the British Museum to consult two biographies of Chaucer: William Godwin’s Life of Geoffrey Chaucer including Memories of John of Gaunt (2 Vols.,1803) and Cabinet Pictures of English Life: Chaucer by J. Saunders (1845); these included a ‘head and shoulder’s portrait of [Chaucer], wearing a hood’ and gave ‘a description of life and manners in Chaucer’s day’ (Diary 9, 18). He also copied a ‘gothic alphabet’ (Diary 18).

The vigorous process of research which Brown developed in the 1840s was one from which he did not deviate when working on other depictions of the past later in his career. These include the carefully researched Biblical illustrations he designed for the Dalziel Brothers in the 1860s, his portrait Cromwell on his Farm (1874, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight) and the murals he designed for Manchester Town Hall depicting scenes from the history of the city (1879–93).

Using the rich collection of drawings by Brown at BMAG as a case study it has been possible to gain a unique insight into his working process as well as a deeper understanding of the ways in which mid-nineteenth-century artists approached their work in response to the changes in historiography. Brown’s drawings show the influences of the changes in historiography, but they also show that artists were the visual counterpart to these changes. Writers wanted their readers to step back in time and empathise with those from the past but as Victorian costume historian Frederick William Fairholt pointed out, ‘the painter possesses still greater power of realising past events, and one that impresses itself more vividly and fully on the mind than a book’ (xi).

Bibliography

Bonnard, Camille. Costumes des XIII, XIV, et XV Siècles 2 vols. Paris: Treuttel & Würtz, 1829–1830.

Brown, Ford Madox. Diary. Ed. Virginia Surtees. New Haven and London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon, 1981.

Brown, Ford Madox. ‘On the Mechanism of a Historical Picture: part A. the design.’ The Germ 2 (February 1850): 70–73.

Catalogue of the household and decorative Furniture, Works of Art, Books and Effects belonging to the distinguished Artist Ford Madox Brown. London: T. G. Wharton, 1894.

Fairholt, W. H. Costume in England: A History of Dress from the Earliest Period until the Close of the Eighteenth Century. London: Chapman & Hall, 1846.

Rossetti, D. G. Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Eds. Oswald Doughty and John Robert Wahl. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965. Vol. 2.

Shaw, Henry. Specimens of Ancient Furniture, drawn from existing Authorities with Descriptions by Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick. London: William Pickering, 1836.

Smith, Roger. ‘Bonnard’s Costume Historique – a Pre-Raphaelite Source Book.’ Costume 7 (1973): 28–37.

Created 22 January 2022