Christ and the Woman of Samaria. 1860. Oil on panel. 13 1/2 x 19 inches (34.2 x 48.4 cm). Collection of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, accession no. 1897P8. Image courtesy of Birmingham Museums Trust, via Art UK under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC). [Click on the images on this web-page to enlarge them.]

This painting was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1865, no. 272. The source of the subject for this painting is John, Chapter IV, verses 4-30. The Bible tells the story of when Jesus leaves Judea to return to Galilee and stops to rest at Jacob's Well near the city of Sychar in Samaria where he encounters a Samaritan woman: "There cometh a woman of Samaria to draw water: Jesus saith unto her, Give me to drink. (For his disciples were gone away unto the city to buy meat.). Then saith the woman of Samaria unto him, How is it that thou, being a Jew, askest drink of me, which am a woman of Samaria? for the Jews have no dealings with the Samarians. Jesus answered and said unto her, If thou knewest the gift of God, and who it is that saith to thee, Give me to drink; thou wouldest have asked of him, and he would have given thee living water… Jesus answered and said unto her, Whosoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again: But whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life."

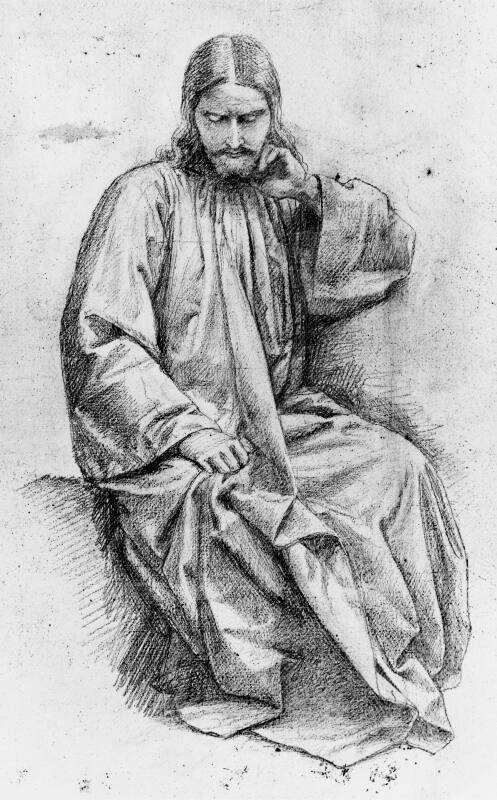

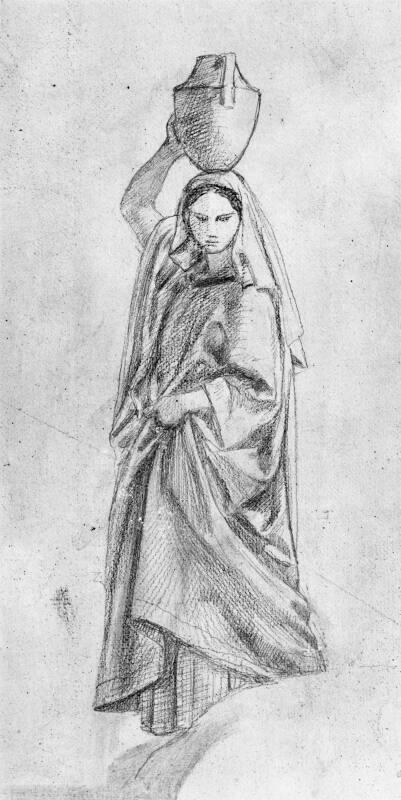

Two of the series of drawings in preparation for this work. Both are in pencil on primed paper, date from c. 1860, and are now in the collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum. They are classed as being in the public domain. Left: Sketch for Christ by the Well. 8 7/8 x 5 inches (22.5 x 12.5 cm), accession no. ABDAG003227. Right: Study for Woman of Samaria. 8 5/8 x 5 1/4 inches (21.8 x 13.1 cm), accession no. ABDAG003226.

The painting follows these preliminary studies very closely.

The subject of Christ and the Woman of Samaria was popular with Old Master painters, including versions by artists such as Vincenzo Catena, Artemisia Gentileschi, Paolo Veronese, Annibale Carracci, Guercino, and Abraham Bloemaert. More recently it had been treated by George Richmond in his version of 1828. In all these paintings the artist focuses his attention on the encounter between Christ and the Samarian woman occurring at the well itself. Dyce's version is unusual in showing the moment just prior to their encounter when the woman is walking down a series of stone steps towards the well and carrying her water jug perched on top of her head. Emily Thomson has pointed out why this particular subject appealed to Dyce: "There is sense of anticipation as Christ, lost in thought, seems unaware of the woman as she approaches. The composition structure is interesting. Christ is certainly the primary focal point and from him our eye is drawn up the path to the Woman of Samaria, whose gaze redirects us again to Christ. Dyce must have been interested in experimenting with novel compositions as he had to solve many such complex problems whilst working on the Queen's Robing Room at Westminster…. The evangelical nature of the story and the way in which it encapsulates Christ's teachings on equality and accessibility would have made it an immensely attractive subject for Dyce" (176).

Marcia Pointon alludes to this painting being the typological successor to Dyce's earlier The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel:

Christ and the Woman of Samaria lends itself, like The Good Shepherd, to a doctrinal interpretation. The woman comes to Christ as the true fountainhead and, having drunk, will return through the narrow gap in the wall, bearing her pitcher to the light beyond. The subject is the typological successor to that other biblical episode by the well, the meeting of Jacob and Rachel, that William had portrayed in the year of his marriage. In Christ and the Woman of Samaria, the figure of Christ is mysterious and deeply melancholy, passive and gloomy, as in The Man of Sorrows, but the strongly architectonic structure of the painting, centering on the diagonal line of deep blue drapery, ensures that Christ is the compositional as well as symbolic core of the picture.[163]

This painting is another in a series of biblical subjects where Dyce used the landscape of the Scottish Highlands instead of the Holy Land is his paintings. As Mary Bennett has suggested about these works:

This can be grouped with a series of subject paintings employing landscapes, which Dyce produced towards the later 1850s …They have the minute precision of the Pre-Raphaelite technique and challenge contemporary photographs for their super-reality and sense of place. Their subjects, whether historical, contemporary or biblical, seem to have the same pervading quietude and sense of time stood still. It is possible that in them Dyce sought to prove to such critics of his earlier "Nazarene" style as Ruskin, that he was fully able to employ the natural vision and geological accuracy which Ruskin advocated, to express profound thought… Dyce was deliberately setting out to represent the scriptures as a contemporary problem by representing them in a concrete, familiar environment which provided emotional and symbolical emphasis. They were not to be viewed simply as literal transcripts of nature nor as landscape divorced from the figures within them. [56]

Bibliography

Bennett, Mary. Artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Circle. The First Generation. London: Lund Humphries, 1988, 56.

Christ by the Well: Sketch for "The Woman of Samaria". Aberdeen Archives. Web. 21 December 2024.

Pointon, Marcia. William Dyce 1806-1864, A Critical Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979, 163.

"Royal Scottish Academy." The Art Journal New Series IV (April 1, 1865): 112.

Study for "The Woman of Samaria". Aberdeen Museums. Web. 21 December 2024.

Thomson, Emily Hope. William Dyce and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Ed. Jennifer Melville. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council, 2006, cat. 49, 174-75.

The Woman of Samaria. Art UK. Web. 21 December 2024.

Created 21 December 2024