In his Pygmalion series (1875-78), Edward Burne-Jones twists the myth of a famous sculptor into a modern fantasy about art and love. All four paintings employ contrasts between light and darkness, precise allocations of space, and the fantasy worlds carved within each. These techniques unify the separate paintings into a cohesive narrative that show the evolution of a supernatural courtship. What separates his version of Pygmalion from perhaps the most famous version — Ovid's — is that the former consciously fantasizes by showing the difference between reality and fiction.

We immediately see the artist play with light in the first painting, The Heart Desires in which earthy tones outside on the left signify the natural light contrasts with a bright, narrowly focused zone of light over the statues signifies divinity. As the series progresses, the jarring contrast between real light and divine light starts to die down — reaching a climax of unification in the third painting when Venus comes to bring the statue to life — and then ultimately completely disappears in the last. If we take Burne-Jones' usage of light in consideration with his precise divisions of space, we can see a purposeful separation of what the artist took to be separate worlds.

We immediately see the artist play with light in the first painting, The Heart Desires in which earthy tones outside on the left signify the natural light contrasts with a bright, narrowly focused zone of light over the statues signifies divinity. As the series progresses, the jarring contrast between real light and divine light starts to die down — reaching a climax of unification in the third painting when Venus comes to bring the statue to life — and then ultimately completely disappears in the last. If we take Burne-Jones' usage of light in consideration with his precise divisions of space, we can see a purposeful separation of what the artist took to be separate worlds.

Very specific organization of space — depth and height — allows the artist to capture these four moments with all their symbolism present. In the first painting, for instance, just as Pygmalion stands right in the middle of the three elevated statues indoors and the two running, breathing girls who have been pushed to the back, psychologically he stands in a miserable state of wanting true love and perfection only found in art. Whereas Pygmalion's feelings are the center of this painting and Burne-Jones shows this by placing him so, the next few pieces reveal the artist's intention at telling the story from several different perspectives.

In The Hand Refrains, the viewer's eyes now encounter a balance between Pygmalion and his statue, and we are more and more removed from the outside world: We have a pretty close, detailed view of the statue's , and the girl outside stands merely as an indistinguishable figure. As we move into a sort of mad scientist's workshop, the artist darkens and washes out the colors of the interior setting, making the statue appear rather grotesque in her pallor and dark, deep-set eyes. Burne-Jones apparently means for Venus, in the The Godhead Fires, to save this statue as she becomes the sole, overwhelming source of light.

In The Hand Refrains, the viewer's eyes now encounter a balance between Pygmalion and his statue, and we are more and more removed from the outside world: We have a pretty close, detailed view of the statue's , and the girl outside stands merely as an indistinguishable figure. As we move into a sort of mad scientist's workshop, the artist darkens and washes out the colors of the interior setting, making the statue appear rather grotesque in her pallor and dark, deep-set eyes. Burne-Jones apparently means for Venus, in the The Godhead Fires, to save this statue as she becomes the sole, overwhelming source of light.

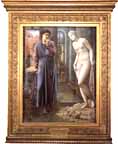

Here Venus works as a life-giving force, like the pool of water she stands upon; here Venus has come abundantly with all of her mythological creatures, and Burne-Jones emphasizes just how fantastic this moment is: Above the Goddess' head hangs a ring of thunder, perhaps recalling the use of haloes in religious painting. Notice how the methodical placement of the two women's arms shows transfer of energy and magic, while there is no longer any girl walking outside. Instead, to the right a dark, deeply carved space with stairs stands in sharp contrast — perhaps to symbolize that after this moment of magic, these stairs will metaphorically lead her to the real world. By the last painting, the dusty light lingers, concentrated, on the stairs in the back of the painting as if to suggest a bizzareness to what we see now: Pygmalion's love and near worship for this mysterious woman.

Here Venus works as a life-giving force, like the pool of water she stands upon; here Venus has come abundantly with all of her mythological creatures, and Burne-Jones emphasizes just how fantastic this moment is: Above the Goddess' head hangs a ring of thunder, perhaps recalling the use of haloes in religious painting. Notice how the methodical placement of the two women's arms shows transfer of energy and magic, while there is no longer any girl walking outside. Instead, to the right a dark, deeply carved space with stairs stands in sharp contrast — perhaps to symbolize that after this moment of magic, these stairs will metaphorically lead her to the real world. By the last painting, the dusty light lingers, concentrated, on the stairs in the back of the painting as if to suggest a bizzareness to what we see now: Pygmalion's love and near worship for this mysterious woman.

Discussion Questions

1. Knowing that the very last painting is entitled The Soul Attains and the very first is The Heart Desires, would you say that Burne-Jones' meant that the statue's soul has now attained or do you think he meant that Pygmalion's soul has now attained?

2a. For what sort of commentary on art does Burne-Jones weave in the supernatural with the real? Does he mean to comment on the Platonic or Neoplatonic ideal. Other works, such as the Perseus series, do not blend myth with reality in this way.

2b. Is he saying that it is absolutely unfortunate and a comedy that Pygmalion should get this great love when it was Venus who brought her to life?

3. Much of the symbolism in this painting is not, like many other Pre-Raphaelite works, hidden and meant to be decoded (ex. The Godhead Fires. In other words the symbolism here does not converge with reality, but rather directly opposes it. Why would Burne-Jones choose to do this?

4. In another highly mythological series, Perseus, Burne-Jones also uses a pool of water in Perseus and the Sea Nymph, only it is now shown to be dark black. Is this merely the sky's reflection? How can we compare and contrast the different meanings behind both pools of water in these separate series?

Last modified 10 March 2008