[These images may be used without permission for any scholarly or educational purpose without prior permission as long as you credit the Hathitrust Digital Archive and the Duke University Library and link to the the Victorian Web in a web document or cite it in a print one — George P. Landow ]

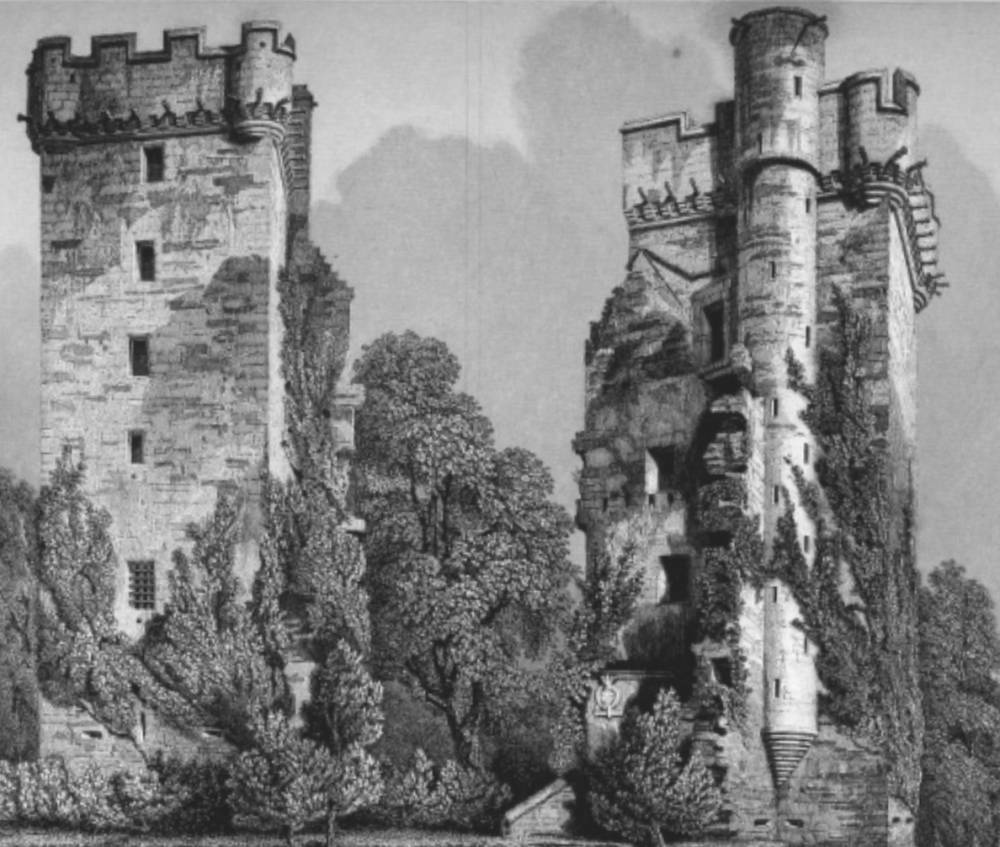

Burgie Castle, Hairn drawn by Robert William Billings (1814-1874) and engraved by J. Sadler. Source: The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1852). Note the people in nineteenth-century costume in the center forground and the homel;y touch of what seems to be sheets drying on a clothes line. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Commentary by the Artist

The pedestrian between Elgin and Forres, who has a little time to spare, may probably visit this quaint spectral-looking tower; but, except by such a casual visitor, it is little known or appreciated. Like its more important neighbour, Castle Stewart, to which, in some points, it exhibits a considerable resemblance, it has several architectural peculiarities worth being preserved, and, among others, a perfect horizontal railing of rain-spouts, must have given it a peculiarly formidable aspect to those whose imagination or ignorance made them believe they were the actual wall-pieces of which they are an imitation. The history of this old stronghold, except as to the mere name and genealogy of its proprietor, is almost a pure blank. It was of old called Burgin. Under this title it occasionally appears in the collection of documents connected with the See of Moray, called the Registrum Moraviense ; but few readers would really care to know how its tithes, which are the object of these notices, were allocated on each occasion, or would even feel much interest in the most important of them all, which relates to a question whether the precentor or sub-chanter of the cathedral church is the titular of certain revenues from the estate.

We are told that, in later years, the edifice belonged to the Dunbars of Grange, a branch of the Dunbars of Mochrum. The domain was attached to the neighbouring Abbey of Kinloss, and it seems to have passed to a private family, through a process of lay impropriation which it would neither be easy nor interesting to investigate. It appears that it came into the possession of Alexander Dunbar, who, in 1567, married Catherine Reid, niece of Robert Reid, Abbot of Kinloss (Shaw's History of Moray, 114). Dunbar, who was sub-chanter of Moray, was appointed a Judge of the Court of Session in the year 1560, the epoch of the Reformation, and of the secularising of the ecclesiastical estates. Neither his ecclesiastical nor his judicial office seems to have saved the owner of Burgie from being compromised in the deadly feuds of his neighbours, and finding it necessary to keep within the walls of his tower, instead of attending to his duties in the Court of Session. Thus it appears on the record of that tribunal, that, in the year 1579, his fellow judges excused him “as now absent, and dare not repair to thir partis throw deidlie feid and enmity standing betwein him and his chief, the Laird of Cumnok, and utheris, the friendis of the surname of Innes, conform to his supplication direct to the Lord President”! (Brunton and Haig's History of the College of Justice, 104). The buildings of the ecclesiastical institution to which Burgie was attached, might have formed an interesting feature in this work, had not rude hands been recently laid on them. The Abbey of Kinloss was one of the magnificent endowments of King David. The abbot was mitred, and sat in Parliament, and the brotherhood possessed broad domains in the fruitful plains of Moray. We are told in the last century how a person who had purchased the abbey lands, observing

that the buildings were far more extensive than were requisite for a kirk, and that the stones were excellently squared, large, and well calculated for buildings of strength, agreed to build a new place of worship for the parish, with which they were well pleased, and then had full liberty to pull the abbey to pieces. [Cordiner's Antiquities]

Yet enough of the building remained, twenty years ago, to make the ecclesiastical antiquary now regret the devastation of later times. A more suitable spot for a monastic ruin cannot well be conceived. Everything around is soft and placid, and rich in centuries of that cultivation which the monks, whose bones have long been mixed with the soil, began in days when all around them was idleness and barbarism. An octagon — probably a chapter-house — of very graceful architecture, then remained to attest the original stateliness and beauty of the abbey church. Like the many Gothic edifices scattered through York, when com-pared with the Minster, it seemed but a secondary object to those who had just left the gorgeous ruins of Elgin; but it had its own peculiar beauties. Beside it stood a considerable cluster of towers and turrets, the remains of the cloister. Among the fragments lying around might be observed a stone coffin, evidence of the very early age at which the spot had been used as a place of sepulture; while a few pear-trees — venerable, yet bearing an ample load of fruit — seemed startlingly to abbreviate the long ages that have passed since the provident monks tended their fruitful orchard. The author of the Statistical Account, writing in 1842, may be left to tell the subsequent fate of this interesting ruin: —

Violent hands have committed depredations on it at various times; and, in fact, it has formed a quarry for almost all the old houses and granaries in the neighbourhood. Still, notwithstanding these attacks, the sides and gable wall of the abbacy stood entire, until they were, within these few years past, recklessly levelled with the ground, and disposed of for building dykes. Xot one stone would have been left on another to mark the spot, had not the trustee on the estate, a gentleman of antiquarian tastes and attainments interdicted the spoliation, and caused the east gable, that narrowly escaped destruction, to be propped by a buttress of mason-work : and there it stands — the sad and solitary fragment of a mansion, wherein the mitred abbot once held his sumptuous banquets, and even princes were his guests.[256]

R. W. B.

Bibliography

The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland illustrated by Robert William Billings, architect, in four volumes.. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Son, 1852. Hathitrust Digital Archive version of a copy in the Duke University Library. Web. 20 October 2018.

Last modified 19 October 2018