In my personal copy, the earliest of numerous copyright dates is 1886, but Van Dyke’s preface is dated 1901. In transcribing the following essay on Hogarth, I have corrected scanning errors and compared it to my print copy and left the authors placing titles of books and paintings between quotation marks. I have, however, added both the books’s original engravings plus works mentioned in the text. — George P. Landow .

EORGE I had gone to the shades and George II was on the throne when the art of Hogarth first began to be talked about in London town. It was something out of the ordinary that an English painter should make a stir in art circles. For time out of mind it had been thought that the dampness of the climate or natural incapacity prevented the native from doing good work, and that none but a Continental could be an artist in the grand style. So long had the outre mer contingent been at court, so long had the foreign cult been established, that no one thought of taking the home product seriously. Even when Hogarth made his appearance he was not considered a rival of the foreigners by any one but himself. He did not win public attention by painting the historical picture better than Rubens. Such large pictures as he painted were coldly received; and Sir Joshua, who voiced British taste in his day, did not regard Hogarth as an artist of the higher sort. Neither did he draw notice to himself by painting nobility nobler than Van Dyck. His portraits were excellent, but the people of his time did not think so. He attracted attention by a new kind of painting — a some thing like personal journalism with the paint-brush — that hit and interested all classes. He created a pictorial "Dunciad," and set the people of the town by the ears with his lampoons on the follies of the times. This made a talk, and London awoke to the fact that there was one English painter who at least had something to say. There was much attention given to what he said, for his truths struck near home; but one fails to find in his own time, or even in the present time, any wide-spread appreciation of how he said it. The artistic quality of his work was little considered. It was William Hogarth, satirist; no one thought or cared much about William Hogarth, painter. His engravings and pictures were accepted for their matter rather than for their manner; and, with the exception of people directly interested in art as art, they are so accepted to this day.

Portrait of Hogarth by Himself. Engraved by Timothy Cole from the original in the National Portrait Gallery. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

It cut Hogarth to the quick that he was not considered a great artist, and that people looked only at his subjects. He was aware of possessing fine pictorial qualities, and wondered that people did not recognize them; yet he knowingly rendered them subordinate by the great prominence he gave to his subject. In his day and country the story-telling theme, the dramatic climax, the moral teaching, were considered an end and an aim of painting. He himself said as much, and so designed his work. There is some thing peculiarly English, perhaps, in this point of view, as has been already suggested. English painting did not concern itself with architectural decoration, but, under Hogarth at least, it seems to have derived from the stage. He was probably the first one to make it a vehicle for illustrating themes pertinent to literature. His serial pictures were the painted acts of a drama — acts written with a paint-brush instead of with a pen. They were read scene by scene, like a book, each picture being a chapter, and each chapter having time- movement. To comprehend them his audience required literary intelligence rather than pictorial imagination. The idea that his pictures were decorative panels, and had artistic qualities pleasing to the eye regardless of their subjects, could have occurred to but few; and yet they were decorative in a very high degree. The story-teller was clever indeed, but the painter was infinitely more clever — in fact, little short of a marvel, considering his period and that he was the first of the school. He quarreled with the "connoisseurs" all his life because they would not recognize him as the equal of Correggio and Van Dyck; but reckoning with the fate that usually befalls the innovator, he seems to have fared not badly. His own generation recognized him as a great satirist and moralist, and it is safe to say that future generations will recognize him as a great painter.

Hogarth was born in London, November 10, 1697. His father was an unsuccessful schoolmaster, and at the time of the son's birth an equally unsuccessful literary hack in London. His uncle, too, had literary aspirations, and wrote satirical poetry that was characterized as wanting in "grammar, metre, sense, and decency." The painter's school education was probably slight, for he was early apprenticed to Ellis Gamble, a silversmith, at the sign of the Golden Angel; and under him Hogarth learned to engrave and decorate silver plate with scrolls, devices, and coats of arms. He was not satisfied with such work, and had hopes of another sort in his youthful mind. "Engraving on copper was at twenty years of age my utmost ambition," he says; and he soon began engraving business cards, tickets, and booksellers' plates. He also designed and engraved the plates of the "South Sea" and the "Lottery," and illustrated Aubry de la Mottraye's "Travels"; but none of these works showed great talent. The illustrations were graceful but not noteworthy, except for what they tell us of Hogarth's early taste, which seems to have had some French bias. The illustrations to Butler's "Hudibras," which followed, were more of kin to Dutch art, and had a coarse, harsh fiber running through them indicative of what was to come.

His ambition soon extended itself to the painting of pictures, and here he began battling against odds. For he had little systematic education as a painter. He was no passed master in drawing, but he had habituated himself to mental impressions of form, and probably "drew out of his head," as the saying is, until the form looked right, resorting at times perhaps to a model with a difficult piece of work. He attended Sir James Thornhill's art school in Covent Garden, and he must have learned considerable there; for Sir James, though not a great popular success, was far from being the incompetent bungler with the brush that people have chosen to consider him. He had not mental strength, and was French-Italian in taste; but he knew how to draw tolerably well, and his line, types, and composition are apparent in Hogarth's large religious pictures. But making due allowance for this teaching and for the occasional traces of foreign influence, like that of Watteau, Teniers, Callot, Chardin, and still Hogarth's education as a painter remains something of a mystery. However it was accomplished, the transition from an indifferent engraver to a master of the brush was quickly made, and was little short of astonishing.

In 1729 Hogarth ran away with and married his master's only daughter, Jane Thornhill, and set up in life as engraver and painter in South Lambeth. The match was not relished by Sir James, but after Hogarth came to popularity (and an income) he was duly forgiven. He began to engrave and publish his own plates, and to paint some small conversation pictures, in measure, like the work of Lancret. Before 1732 he had painted the "Wanstead Assembly," the "Meeting of a Committee of the House of Commons at the Fleet Prison, 1729" (one of his most charming pieces of tone and color), scenes from the "Beggar's Opera," the "Indian Emperor," and some small portrait groups.

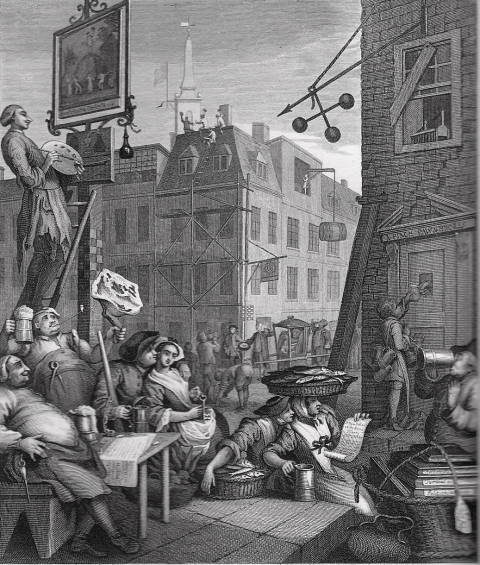

The first plate in The Harlot's Progress. William Hogarth (1697-1764). 1734. Engraved by F. F. Walke.

Between 1730 and 1733, he painted his first notable success, the "Harlot's Progress." There were six pictures in the series, and they were afterward engraved. Hogarth explained the series by saying: "I have endeavored to treat my subject as a dramatic writer. My picture is my stage; my men and women my players, who, by means of certain actions and gestures, are to exhibit a dumb-show." He could not have made a more exact explanation of the subject; and the subject was the only thing in which his audience was interested. The "Harlot's Progress" was a moral tale in paint, carrying over six acts. The play — the story — was the thing. Had the series not been destroyed by fire, we might to-day find that there was something else to it than the "dumb-show" — something of decorative beauty in form and color. But the subject of it rather than the art of it caught the fancy of the town, and Hogarth immediately followed up its success by the "Rake's Progress," in eight pictures, now in the Soane Museum. This was not so successful with the populace, though it made a savage lunge at high life. The two series had made him famous, and his satires were in demand; yet at this very time the painter in him seemed to revolt at mere popular success, and he turned back sharply to an early ambition of excelling in the "great style of history-painting. "

Parts 1 and 5 of Marriage à la Mode Left: [Arranging the marriage]. Right: The Death of the Earl.

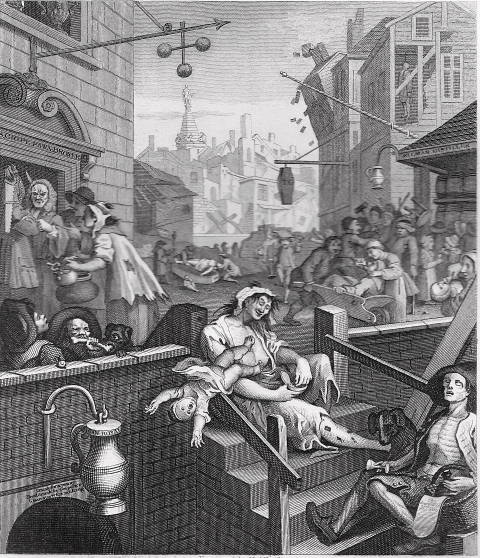

In 1736 he produced two enormous pictures for St. Bartholomew's Hospital, with figures over life-size, representing the "Pool of Bethesda" and the "Good Samaritan." They were a first attempt at large pictures, and though not exceptionally good, they were not exceptionally bad, as we have been told. They displayed ability, but there was no applause for them at the time; and Hogarth, not wishing to sink into a "portrait manufacturer," as he put it, returned to his small pictures, his plates, and his public. The "Distressed Poet," the "Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn," the "Enraged Musician," came next; and then, after a unique auction of his pictures, at which the two "Progresses" fetched only two hundred and seventy-three pounds, he produced his "Marriage à la Mode," six pictures in a series, now in the National Gallery. After this he did some portraits of Lord Lovat, Mr. Garrick, and others; got up "Industry and Idleness," twelve plates illustrating apprentice life; painted the effective "March to Finchley"; engraved "Beer Street," "Gin Lane," and the "Four Stages of Cruelty," three uninteresting and coarse studies in criminology; and painted an insular, ill-natured fling at the French, called the "Roast Beef of Old England" or "Calais Gate." In 1752 he produced two more large historical pictures — one of "Moses Brought to Pharaoh's Daughter," now in the Foundling Asylum, and one of "Paul Before Felix," belonging to the Society of Lincoln's Inn.

Left: Beer Street. Right: Gin Lane.

Hogarth was now fifty-four, and had perhaps done his best work, but his fighting spirit was by no means stilled. He wrote a book called the "Analysis of Beauty," to "fix the fluctuating of taste," in which he went out of his way to attack the "black masters" of Italy, and incidentally to assert his own superiority. In reality his quarrel was more with the picture-dealers who brought over the "ship-loads of manufactured Dead Christs, Holy Families, and Madonnas," than with the old masters. "The connoisseurs and I are at war, you know, and because I hate them they think I hate Titian — and let them." But the "Analysis of Beauty" was not a very lucid performance (Walpole called it "silly"), and it brought Hogarth many hard knocks from his enemies. He who had been such a biter soon felt himself bit, and "Painter Pugg," as they called him, afforded considerable amusement to the satirists of the day.

Left: The Election (Part 2. “Canvassing for Votes”). Right: (Part 3. “The Polling”)

He went on, however, but with slackened vigor, to paint the "Election," four satirical canvases now in the Soane Museum, and to get out some prints of minor importance. The fancy for historical painting came to him once more, and he painted three pictures as an altarpiece for St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, now in the Academy of Clifton. For these he got five hundred pounds, and was vastly proud of getting such a sum for his work. In 1757 he was appointed sergeant-painter to the king, and thought to confine himself thereafter to portraiture; but two years after his appointment he announced that he would finally abandon the brush for the graver. Before doing so he painted the "Lady's Last Stake" and the "Sigismunda" in the National Gallery, for which Mrs. Hogarth is said to have acted as the model. He did take up the graver again, but with weakened wit, producing the plates of the "Times," which got him into a quarrel with his whilom friends Churchill and the "heaven-born" Wilkes. The quarrel resulted in Hogarth's pride getting badly battered, and Wilkes having his cock-eyes perpetuated in caricature. After that there is little to record. The artist's work ended with the plate of the "Bathos," and the man died on October 26, 1764, at his house in Leicester Fields, where he had lived most of his life.

Such, in brief, was the life of William Hogarth — a life that is both illustrated and contradicted by his pictures. To the public he was a pugnacious little man, one who believed in justice and up rightness, and never minced words in denouncing social immoral ity. His subjects would indicate the coarse-grained satirist, the man who meant to shake the sides and at the same time preach a sermon. He was regarded as something of a Wilkes in paint — a slasher and a bruiser of reputations for righteousness' sake, a denouncer of evil, an opponent of the old masters, and one knows not what else besides. Undoubtedly he was in measure the product of a degraded time, and had some degraded instincts that cropped out in his works; but these were only a part of the man, and the poorer, more ignoble part at that. There was another side, about which he said little, because his public was not interested, but it is fully revealed in his pictures. The pictures show that under the coarse mask of the satirist was a feeling as refined as any known to English painting. Hogarth the satirist and Hogarth the painter were like two different natures. One was savage, brutish, almost hyena-like in the laugh over the unwholesome; the other was the embodiment of tenderness, delicacy, and charm. The brutish nature is apparent in many plates and paintings: the "Modern Midnight Conversation," the "Election," the "Progresses," the "Marriage à la Mode."

The Rake's Progress Plate VI, "Gaming House Scene,".

Take the "Rake's Progress," for instance, and study the tragic horror of the gambling-scene — the cold-bloodedness of the hands grasping the money, the frenzy of the young man kneeling upon the floor, his hands clenched in agony, the utter indifference of those about him.

Two plates from The Rake's Progress. Left: Plate III, "Tavern Scene". Right: Plate VIII, "Scene in Bedlam".

Consider the picture called the "Orgies" — the uproar of the drunken women, the bestiality of the faces, the coarseness of the actions, the gutter quality ofthe whole scene. Pass on to the last picture, the "Mad house," where the rake lies on the floor in the foreground, with out mind, feeling, or even clothing; around him hideous types of the maniac, and back of him gloom, chains, grated windows, and the grave. It is not possible to sup more full of horrors. But dismiss the subjects from mind, study the pictures for what they look rather than for what they mean, and see with what wonderful taste and refinement the man has painted them. Notice the gamblers at the table for their grouping and action; see with what skill the painter has drawn the room and filled it with atmosphere, and with what charm he has woven through that atmosphere his subtile and beautiful scheme of color. In the "Orgies" picture notice the woman in the foreground pulling off her shoes and stockings for the dance; and, as art, could anything be more beautiful than the abandon and grace of the action, the beauty of the color, the setting and relief of the figure? See again the circle of women around the table; how delicately the reds, blues, yellows, and grays of the dresses harmonize and run together! Notice the angle of the room; the Roman emperors on the wall; the little girl standing at the door, so beautiful in color and painting. Could anything be more exquisite than this treatment? And there, in that charnel-house of the mind, the mad-house, are two women standing in the background, one dressed in pink silk, the other in silver-gray, than which Watteau never painted anything more graceful or more delicate. In the painter's mind, what mission had these beings of another sphere in such a place? Were they not put there as atoning loveliness? It must have been a strange imagination that could entertain such visions of beauty and deformity at one and the same time — a strange nature that could be so coarse in thought, so refined in feeling and execution. Jan Steen occasionally reeked of the bagnio without knowing it, and Goya was sometimes hideous through mental infirmity; but Hogarth knowingly compounded viciousness with purity, and married Beauty to the Beast; he consciously gilded the gutter with the rainbow hues of heaven.

There is no mistaking the moralist in Hogarth. He depicted vice with a purpose. Yet one may doubt if, as a painter, he liked this moralizing with the paint-brush any too well. From his various attempts at historical painting, one might conclude that he wished to paint other things, but the public would not allow him to do so. His historical canvases attracted little notice, but his satires were applauded. He was a man who reckoned with success, and perhaps thought it better to be first as a satirist than last as a painter in the grand style. In other words, he supplied a demand, and possibly contented his own soul by putting forth his work in a refined, painter-like manner.

In his story-telling subjects his strong feature was his mimic sense and his power of characterization. The influence of the theater appears here again. Shows of all sorts interested him as a child, he tells us; the dramatic was his natural gift, the stage his study, and a knowledge of physiognomy one of his earliest acquire ments. Characterization came to him as it might to a trained actor. He knew almost infallibly how a feeling or emotion made itself manifest in face or action. Look, for instance, at Mr. Cole's engraving ofthe detail from the "Marriage à la Mode," where the marriage contract is being drawn up, and see how strongly hit off are the flippant vanity of the young fop admiring himself in the mirror, the peevish listlessness of the prospective bride playing with her ring. It is a milder piece of sarcasm than Hogarth usually indulged in, but how absolute it is! The people of the "Progresses," the "Election," and the "March to Finchley" are just as decisively epitomized.

Left: Garrick and His Wife. Engraved by Timothy Cole from the original in Windsor castle. Right: Marriage à la Mode [detail]. Engraved by Timothy Cole from the original in the National Gallery, London.

Characterization shows again in his portraiture. He objected to "manufacturing" portraits, and yet some of his noblest pieces are in this field. Individuality of form and feature he grasped unerringly, even when he had himself for a model, as in the small picture engraved by Mr. Cole. The "Garrick and Wife" at Windsor Castle is a little more precise and non-elastic, but shrewdly observed and full of force; and the half-length of his own wife, belonging to Lord Rosebery, is one of the most refined pieces of vital portraiture in the whole reach of the English school. The color-scheme alone — a scheme of grays touched with lilacs — forestalls the color delicacy of to-day, and the face shows as dis tinguished drawing as Hogarth ever did. The "Mrs. Dawson" at Edinburgh, and the "Peg Woffington" in Sir Charles Tennent's collection, have much of the same quality. The portraits of "Miss Fenton as Polly Peacham," and Hogarth with his dog, in the National Gallery, are of a much poorer quality; and even the panel showing the heads of Hogarth's servants, though forceful, is lacking in color and somewhat hard in execution. The feeling that they once actually lived, however, is as strong as with the "Captain Coram" or the sketchy "Lord Lovat." Character marks all his heads.

His large religious pictures in the Foundling Asylum and in St. Bartholomew's Hospital were experiments. Hogarth knew little about large-scaled figure-painting, and when he designed such work he did little more than enlarge a small conception. In the "Moses Brought to Pharaoh's Daughter," the princess is a pretty "Marriage a la Mode" type, cleverly handled, as is the girl back of her; and Moses is, of course, a Drury Lane urchin in green dress and flaxen hair. The "Pool of Bethesda" has an amphitheater of ruins in the background, a figure of Christ lacking in dignity, a typical street mob about him, a girl with a white cap like a Hals, a woman in white like a Chardin, a nude figure like a Boucher, and a man in the foreground like a Titian. The "Good Samaritan," on the side wall next it, is no improvement. They are all well enough painted, but a bit disjointed and incongruous in conception. The mind of Hogarth did not readily rise to nobility of type after dealing with models from the London slums. Occasionally we see in his pictures a figure that is airy and graceful, but these appear more at home in his small conversation groups, and in his single-figure pieces, like the "Lady's Last Stake" and the "Sigismunda." The figure in the former approaches to nobility, and so far as the type is concerned, the "Sigismunda" is elevated enough; but in painting it Hogarth was trying to outdo a supposed Correggio, and overworked the canvas. It lacks in freedom and spontaneity.

Hogarth was not a landscape-painter, yet he knew a great deal about landscape, as the first picture in the "Election" series discloses. The "Calais Gate," too, shows knowledge of sky and sunlight; and in the first picture of the "Marriage a la Mode" series there is a street or square, seen through a window, that is astonishing in its delicate drawing, its value in light, and its feel ing of air. The "Arrest" in the "Rake's Progress" shows conclusively that he knew how to paint a street with air in it, sky over it, and buildings placed in their proper planes. In fact, Hogarth could paint almost anything, except animals, and in nothing was he stronger than in still life. His cups and saucers and table cloths are as beautiful as Chardin's; his beef in the "Calais Gate " is worthy of any Dutchman; and neither Pater nor Watteau was his superior in painting silks, draperies, and furniture. Technically he was uneven in drawing. Sometimes he was harsh and lacking in freedom, at other times quite rhythmical and flowing. He seldom drew like an academician, trained to ease by knowledge, and giving the whole truth of form. On the contrary, he frequently cut out the accidental by a loose, broken line, and summarized an object, like Ostade or Millet. Knowledge of anatomy he showed in more than one nude; and motion, life, abandon, he pictured well in the " Orgies" picture of the "Rake's Progress," in the " Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn," in the " Marriage à la Mode." All his people have weight and bulk, and they all stand or sit firmly. This is noticeable in his own portrait, in the "Lord Lovat," in the fat singing-master of the fourth "Marriage à la Mode" picture.

Moreover, all Hogarth's people hold their places by virtue of their atmospheric setting. Each one is given a proper value. Not one of the old English masters understood the problem of enveloppeem> — the placing of figures in atmosphere — so thoroughly as Hogarth. I have only to refer to the little family group (No. 1153) in the National Gallery for confirmation of this. The figure of the man standing at the right, the group about the table, the table itself, are absolute in their truthful relations to the foreground, the room, and the wall decorations. The setting is so true that the air of the room can be almost felt. Look again at the "Duel" scene in the "Marriage à la Mode," and a similar effect is apparent, though the illumination is different. It is one of the first candle- and fire-light pictures painted in England, and it is a little arbitrary in its lighting; but the relation of objects is not disturbed. Everything keeps its place, and the picture holds together as a whole.

Hogarth was not less skilful in the handling of color. There is a sharp brick quality often shown in his flesh that is peculiar to English painting, but in other respects he is most forceful while being most subtile. His tones are usually pure, though he often used broken notes to attain delicacy. All colors — reds, blues, greens, grays, Jan Steen's yellows — are seen upon his canvases, and they seem to be laid on easily, without kneading, mixing, or emendation. Moreover, they are to-day in an excellent state of preservation; for Hogarth used no bitumen, like those who came after him, and tried no experiments with fugitive colors. Many faces by Reynolds are stricken with a death pallor; Raeburn's shadows are pot-black; and Turner's skies have turned chalk-white or lemon-yellow: but Hogarth's colors are as clear and pure as when first painted. He knew very well what he needed, and resorted to no studio expedient in obtaining it. Frank, honest man that he was, he painted in a frank, honest way. His handling is not remarkable, but it is effective.

The Shrimp Girl engraved by Timothy Cole from the original in the National gallery.

The sketch of the "Shrimp Girl" shows both his brush-work and his color to advantage. It is a scheme in reds, browns, and grays, done swiftly, but with knowledge, taste, and skill.

His composition was perhaps his weakest feature. It is the final and convincing proof of the influence of the theater upon his art. One cannot look at the "Progresses," the " Marriage à la Mode," the "Lady's Last Stake," without realizing that they are stage tableaux, the painted climaxes of a play. The setting of the scenes, the grouping of figures, the disposition of properties, the planes in which the figures stand, the exits and the entrances, all point to the theater. He probably found his characters in real life, but he arranged them on the boards like a stage-manager. This led to something akin to the artificial, to overmuch detail, and to the crowding of space. The object of many accessories was, of course, to suggest the tale that could not be spoken; and for the story-telling purpose it was effective enough, but as pictorial composition it was sometimes unfortunate. Composition never was a strong feature of the English painters, and Hogarth, the beginner, was not always successful with it. As with many another painter, his least elaborate compositions were his best.

There can be no doubt that Hogarth's instincts were those of a painter. His feeling for color and air, his handling of the brush, his sense of delicacy and refinement in the placing of tones, all mark him as an artist whose medium of expression was neces sarily pigment. His trenching upon literature in his subjects, his constant jumbling of pigment with figment, were requirements thrust upon him by his age and audience; but neither that, nor the fact that his audience applauded him for his satires rather than for his painting, invalidates the excellence of his art. The raison d'etre for the subjects has passed away, but the painting still lives to give its author high rank. It is worthy of more study than it has yet received, for there were only four great originals in old English painting — Hogarth, Gainsborough, Constable, and Turner. Hogarth was the first, and some there be who do not hesitate to say he was the greatest of them all. [15-25]

Bibliography

Old English Masters Engraved by Timothy Cole with Historical Notes by John C. Van Dyke. London: Macmillan, 1902. The Hath Trust’s online version that I have used as the basis for the text above was published by the Century Club in New York and is otherwise identical to the London edition. Web. 22 April 2021.

Last modified 22 April 2021