The Sleeping Congregation

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

Engraved by C. Armstrong

Source: Complete Works, Between p. 156 and 157

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[This image may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose.]

Commentary

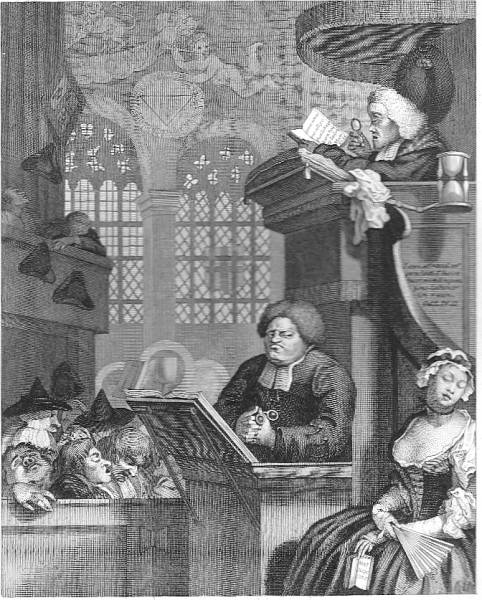

The affinities between William Hogarth's etching "The Sleeping Congregation" (1736, 1762) and Hablot Knight Browne's "Our pew at church" (1849) reveal not merely the direct influence of specific satirical pieces by the eighteenth-century narrative visual artist upon Phiz, but the spirit that the nineteenth-century illustrator imbibed from Hogarth's prints and paintings, particularly in the deployment of embedded clues as to how to decode the underlying satirical message. As Michael Steig notes in Dickens and Phiz (1978),

In both, the clergyman myopically reads his text from a Bible propped up on pillows; and in both a young woman is a principal focus, Mrs. Copperfield with her hands crossed and her eyes demurely cast down, and Hogarth's wench with her hands similarly crossed and her eyes closed in sleep. As Hogarth's clerk slyly regards the sleeping woman out of the comer of his eye, so Mrs. Copperfield is the object of male attention in the person of a black-haired, bewhiskered gentleman who can be no one but Murdstone contemplating the "bewitching young widow" and her small annuity as well, no doubt. The clinching evidence that Browne bad Hogarth's engraving in mind is that whereas Hogarth's sleeping female has her prayer book open to the marriage service, indicating where her thoughts and dreams really are, in Phiz's version it is Mr. Murdstone who thinks about marriage, and it is his prayer book which is open: in one of the steels (IA) the letters "MARR" are clearly discernible. [Steig 115]

The ostensible subject is merely a country congregation's having succumbed to the sleep-inducing qualities of their elderly parson's sermon; however, the larger theme upon which Hogarth, a visual artist working in the same vein as the greatest literary satirist and social commentator of the age, Alexander Pope (1688�1744), elaborates here is the decadence and irrelevance of the Anglican Church in eighteenth-century England. That the near-sighted preacher (above) is so caught up in his sermon that carries on, oblivious to the fact that he has put his congregation to sleep, is situationally ironic, especially when one considers that the text of his sermon is "Come unto me all ye that Labour and are Heavy Laden, and I will give you Rest." However, immediately beneath his pulpit, sin is actively at work as the clerk, the print's central figure, oggles the buxom maiden who has fallen asleep over the Common Book of Prayer's marriage service (one of the points that this eighteenth-century engraving shares with Phiz's Copperfield illustration). But in an age of migration from villages to towns and acute social suffering, such a church, asleep at the switch, so to speak, is not merely mildly amusing but reprehensible, for the guardians of public morality and models of charity are neither vigilant nor pure. To make the Wesleyan jest more pointed, Hogarth has the hats of the musicians in the gallery tumbling downward while the only people who are obviously awake are two old women whose hats identify them as witches!

Bibliography

Complete works of William Hogarth ; in a series of one hundred and fifty superb engravings on steel, from the original pictures / with an introductory essay by James Hannay, and descriptive letterpress, by the Rev. J. Trusler and E. F. Roberts. London and New York: London Printing and Publishing Co., c.1870.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield, il. Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. 2 vols. London and New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Painting

William

Hogarth

Next

Last modified 21 February 2010