What then is steampunk fashion? Perhaps the most straightforward explanation is that it is fashion that could be found in a steampunk book or film. . . . It would be more accurate to say that steampunk fashion is fashion inspired by the aesthetics, themes, and styles of the steampunk trend in the same manner that literature, art, film, and music are each in their own way. And in fashion this is characterized by Victorian era clothing drawn from across the world, made from rich and textured fabric, accented by accessories, and embodying the spirit of a past that might have been but never was. [International Steampunk Fashions, 9; emphasis added]

Two sides of the steampunk aesthetic, Left: A vision of a sail and steam-driven airship by In Strict Confidence, Germany. Right: A Steampunk Picnic by Bernard Rousseau, France. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

International Steampunk Fashions is not an academic book and it doesn't come from an academic publisher. Schiffer Publishing have a very long list, and many of their heavily illustrated books take the form of surveys of collectibles. Their catalogue contains not only books for serious collectors of Staffordshire figures, antique toys, and nineteenth-century sculpture but also ones for those fascinated by beer signs, glass bells, vintage kitchen towels, inkwells, wedding cake toppers, yo-yos, and corkscrews (I counted six books on corkscrews alone). Many of their publications are aimed at collectors and would seem essential to anyone collecting, say, Freeman-McFarlin pottery manufactured between 1951 and 1980, Matchbox toys (10 books), antique mining equipment, or watches made by Rolex, Breitling, or Patek Philippe. Their publications also appear essential for designers and architects, and their Victorian-focused offerings provide a treasure trove of information about the objects that filled nineteenth-century homes and bore the impress of nineteenth-century lives.

Their offerings about Victorian subjects range from books on architecture to books on furniture, glassware, clothing, dollhouses, and objects created of wax, shells, and hair inside bell jars. A work like John Whitenight's Under Glass: A Victorian Obsession obviously falls within the purview of the Victorian Web, but why should we concern ourselves with International Steampunk Fashions, a book of photographs of twentieth- and twenty-first century unorthodox fashion of the sort that will never appear either in mass market stores or on Paris runways? One answer is that steampunk fashion, like Victorian scholarship, attempts to make nineteenth-century matters matter. Much Victorian scholarship and criticism aims at making some aspect of Victorian life and thought understandable and relevant and, like Steampunk fashion, much of it comes off as eccentric and pleasing only to those who share the author's interests or obsessions.

The Victorian period or era or age has always been interpreted by its successors, consciously or not, in terms of goals related to the writer's present. Thus, Lytton Strachey wrote his amusing falsifications of the Victorians to free his contemporaries from the burden of belatedness, from the feeling of being overpowered by those literary giants filled with almost demonic energy. The beginnings of new interest in things Victorian also took the form of seeing the nineteenth-century as to some extent congenial to the mid-twentieth. As one of my teachers pointed out half a century ago, the Victorian revival in literary studies occurred in part because of the discovery of the quirks or flaws of major figures that made them seem less gigantic and “more like us.” So Dickens's having a mistress and Tennyson's ability to put himself into a trance by chanting his own name eventually led scholars and critics to look at them and see both new greatness and new similarities to their own time. Of course, one result of such an approach was to deny — or simpy remain ignorant of — the central importance of Victorian religion to major writers like Thomas Carlyle, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and John Ruskin. To be an atheist was to be, well, more modern. There's nothing wrong in itself with finding similarities between then and now, and some impeccable scholarship, such as Tom Standage's The Victorian Internet, mines the previous century to show that we are connected in unexpected ways.

Steampunk adornments and accessories. Left: The Wykcliff Ocular Assembly Mk2 by Mark Corduroy Creations, UK. Middle: Brooch by Marija Jillings of Jazz Steampunk, the Netherlands. Right: Maurice Grunham Redstar, photography by Gillis Michel, France. “The gear is an easily recognized symbol of steampunk . . . [which] joins related devices such as flywheels and pistons as the "power lines" of the steam age. . . . Goggles are often encountered in steampunk clothing and imagery, and this can create the misleading impression that they are somehow fundamental to the steampunk look. Certainly, goggles are associated with both science and mechanized travel. both of which are common themes in steampunk” (13). [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The term Steampunk refers to the kind of world created in The Difference Engine, a dystopic science fiction novel by Bruce Sterling and William Gibson set in an alternate Victorian reality after Charles Babbage succeeded in creating his mechanical computer or difference engine. In this alternate Victorian age a giant steam-driven mechanical computer, which occupies the entire British Museum, has become an agent of totalitarian control. The previous works of Gibson, who invented the word cyberspace, and Sterling centered on similarly dark views of networked digital information technology. Gibson's enormously influential Neuromancer trilogy and Sterling's Islands in the Net, Mirrorshades, and Globalhead were labelled cyberpunk, particularly by older science fiction authors and critics who did not like its protagonists, worlds, or fascination with extrapolations of the Internet. When Gibson and Sterling explored a world whose computers are steam-driven — mechanical rather than digital — this new world became known as Steampunk. Punk fashion or punk rock have little to do with it.

Cyberpunk scifi presented readers with a terrible world ruled by murderous all-powerful giant corporations in which the most attractive characters exist outside the law and somehow or other survive amid violent events. But Cyberpunk's depiction of hackers, some of whom can leave their bodies behind and mentally travel in the future Internet, attracted many readers who tended to ignore the dominant dystopian worlds they presented. In a similar manner, readers of The Difference Engine took from that dystopian novel an imagined world that had computing but not the digital, a steam-driven world in which the physical mattered, not the virtual. As the Schiffer volume explains, “From great machines to majestic airships, from smoke-filled factories to the palaces of the mighty, the term 'steampunk' conjures up innumerable images of science, industry, grandeur, and wonder.”

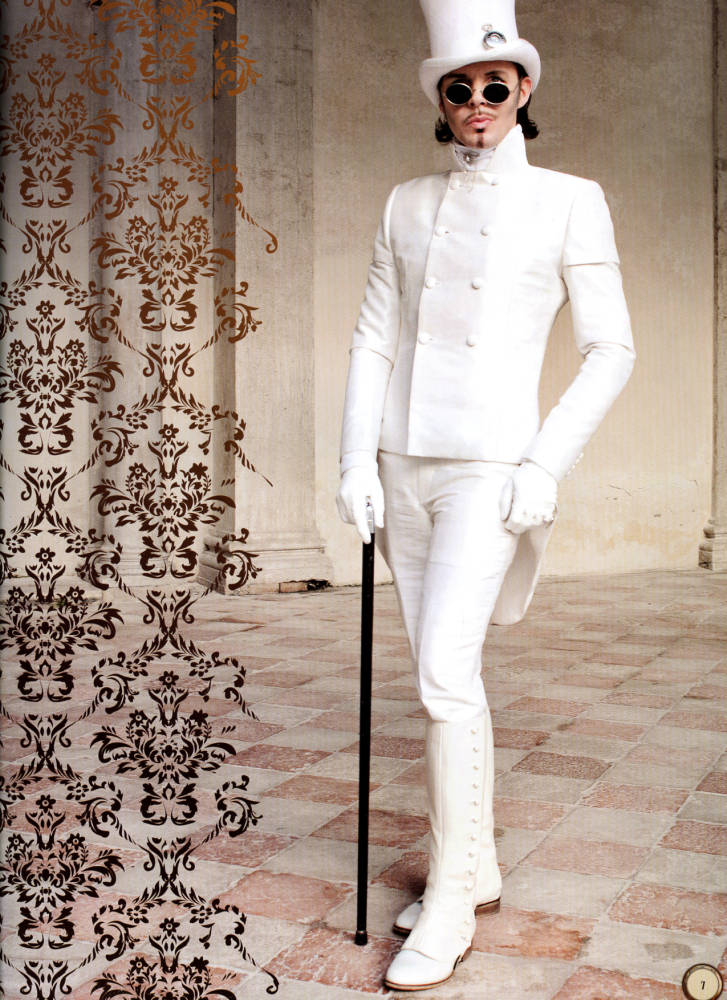

International Steampunk Fashions justifies itself with the claim that although steampunk may have originated in literature and film, such as The Difference Engine and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, its most important “manifestations have, in recent years, been predominately, or even entirely, fashion-oriented. To many, steampunk is as synonymous with corsets, top hats, goggles, and gowns as it is with airships or difference engines.”

Left: Sarah Harris, courtesy of Insomniac Studios, St. Louis, MO, USA. Middle left: A riff on a female Mad Hatter, photograph courtsey of Dennis Totin, USA Middle right: Johan Rydberg, steampunk monsterologist, Sweden. Right: Pierre Leszczyk, model and photographer, Germany.

As the photographs I've placed in this text demonstrate, this “spirit of a past that might have been but never was” intentionally makes strange inflections of costume and fashion history. Women (and a few men) wear corsets over their clothing while gears and goggles and mysterious steam-driven apparatuses appear as accessories, sometimes hanging from a belt, sometimes worn on the back like a knapsack. The “never was“ fantasy element encourages playing with races, gender roles, and economic positions. Women's bosoms are no barer than those that appeared in an upperclass Victorian dining room, but women's clothing that exposes legs, thighs, and garters exemplify a major reinterpretation of the Victorians, a new intonation of them such as we find in the novels of Sarah Waters and Peter Carey. Men and women both wear top hats upon whose surfaces often appear goggles, gears, dials, and other mechanical decorations, such as we see in three of the four photographs immediately above.

Of course, the people who wear these costumes of imaginary Victorians rarely wear them on the street or elsewhere in their everyday lives. They wear them at conventions, such as Comicon, which resemble elaborate fancy dress costume balls without the dancing. These conventions, like academic conferences, include seminars and keynote addresses, but instead of booths containing publishers' representatives, theirs contain self-published authors, artists, and merchants of collectibles, such action figures, comic books, and a wide range of memorabilia. Large numbers of the attendees wear costumes, many of which they have made themselves, that identify them as characters from comic books, graphic novels, televison, film, japanese anime, and video games. Interestingly, those dressed as steampunkers seem to be the one group whose members invent their characters rather than base them on specific books, films, or games.

Four versions of steampunk fashion for women. Left: Model and fashion designer Leah D'Andre, photography by Oleg Volk, USA. Middle left: Steampunk Felicity, by Steampunk threads, USA. Middle right: Lady Georgina Marsh, photography by Mart Soulstealer, UK. Right: Kato, designer and model, www.steamcouture.com, USA.

Just as I began to write this notice of International Steampunk Fashions, I happened upon A. N. Wilson's TLS review of Andrew Sanders's In the Olden Time: Victorians and the British past (2013), which opens with the remark that “you might think that the Victorians gloried in the past, or wanted to inhabit it.” Why else, asks Wilson, did Sir Edwin Landseer paint Queen Victoria and her consort Prince Albert in the guise of earlier monarchs, why did the government rebuild the Houses of Parliament in Gothic Revival style after fire destroyed them, and why did the historical novels by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Charles Reade enjoy such immense popularity? Not, argues Wilson, because Victorians cared deeply about the past. Victorian “reconstructions of a fake past no more imply antiquarian reverence on the part of the Victorians than does the reproduction of the Roman Forum in Las Vegas. If anything, the opposite.” So how does the Victorian approach to the past differ from ours? Do we see

see the "real" past, while the Victorians babyishly made an ersatz past for their own peculiar political or psychological reasons? . . . It would be a bold person who advanced any such boast. Who is to say that, for example, the English Heritage Visitor Centre at Stonehenge is more or less Stone Age than the henge as viewed by Tess of the d'Urbervilles in the moonlight? . . . A difference, perhaps, between us and the Victorians is that we fool ourselves, whereas they were quite blatant about recreating a past they must have known to be invented.

At least those who embrace Steampunk know that they have imagined an imaginary world and not discovered a real one. This volume on steampunk fashion makes clear that its followers are “quite blatant” about creating an invented past, one more desirable, more comfortable than the real one whatever that, according to scholars, might have been.

The line between steampunk and period Victorian is extremely narrow, and often the two are indistinguishable. They are separated only by steampunk's status as science fiction, albeit heavily inspired by the historical fact of the Victorian period. This is generally accomplished in one of two ways. The proto steampunk stories of the nineteenth century can be seen as a parallel to our own science fiction: that is, a view of the future from the present. For the Victorians, this meant imagining a future that looks dramatically un-modern to modern eyes. Submarines, space travel, aircraft, and mechanized life were all imagined by the Victorians, but while some of these came very close to the mark, they still differed from where the future actually went. For modern writers, with the benefit of modern science, steampunk becomes a re-imagining of the nineteenth century with a view of where science will one day go. In this way, steampunk often works to translate modern concepts such as the computer revolution, spy thrillers, noir mysteries, and even the Internet into a Victorian context using Victorian technology. Steampunk becomes the perfect blending of alternate history and science fiction. [12-13]

Bibliography

Gibson, William, and Bruce Sterling. The difference engine. New York : Bantam Books, 1991.

Sanders, Andrew. In the Olden Time: Victorians and the British past. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's Online Pioneers. London: Phoenix, 1998.

Victoriania Lady Lisa. International Steampunk Fashions. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2012. Pp. 192. ISBN 978-0-7543-4207-3.

Wilson, A. N. “So bluff! So burly. So truly English.” Times Literary Supplement (January 3, 2014): 5-6.

Last modified 18 January 2014