This article is a revised and extended version of material that appeared in Chapter 2 of my monograph Neo-Victorian Fiction and Historical Narrative: The Victorians and Us (Palgrave, 2010).

ulian Barnes is often considered an exemplar of postmodern writing,

and several of his novels have entered the postmodern canon because of

their exploration of the boundary between history and fiction and the

issue of identity. With his 2006 novel Arthur & George, Barnes has

taken his concern with history and identity into the nineteenth

century. Arthur & George traces George Edjali’s wrongful conviction

for the Great Wyrley Outrages of 1903 and Arthur Conan Doyle’s

subsequent campaign to overturn the verdict. In adopting the creator

of the most famous fictional detective as one of his protagonists,

Barnes clearly asserts his novel’s affinity with the genre of

detective fiction. Indeed, the novel explicitly positions its readers

as detectives by requiring them to decode the identities of the

protagonists, who are teasingly referred to by only their Christian

names in the title and for the majority of the opening section of the

novel. Barnes’s novel is one of a number of neo-Victorian fictions

which use the tropes and conventions of detective fiction to explore

the nature of the relationship between the present and the past.

Focusing on the related issues of evidence and justice, Arthur & George raises questions about the possibility of knowing the past and

the responsibility that the present owes to the past.

ulian Barnes is often considered an exemplar of postmodern writing,

and several of his novels have entered the postmodern canon because of

their exploration of the boundary between history and fiction and the

issue of identity. With his 2006 novel Arthur & George, Barnes has

taken his concern with history and identity into the nineteenth

century. Arthur & George traces George Edjali’s wrongful conviction

for the Great Wyrley Outrages of 1903 and Arthur Conan Doyle’s

subsequent campaign to overturn the verdict. In adopting the creator

of the most famous fictional detective as one of his protagonists,

Barnes clearly asserts his novel’s affinity with the genre of

detective fiction. Indeed, the novel explicitly positions its readers

as detectives by requiring them to decode the identities of the

protagonists, who are teasingly referred to by only their Christian

names in the title and for the majority of the opening section of the

novel. Barnes’s novel is one of a number of neo-Victorian fictions

which use the tropes and conventions of detective fiction to explore

the nature of the relationship between the present and the past.

Focusing on the related issues of evidence and justice, Arthur & George raises questions about the possibility of knowing the past and

the responsibility that the present owes to the past.

Many neo-Victorian novels adopt a dual plot structure that sees a twentieth- or twenty-first-century detective investigating a nineteenth-century “crime.” The most famous example of this is A. S. Byatt’s Possession: A Romance (1990) which follows the literary detective quest of twentieth-century scholars Maud and Roland into the private lives of nineteenth-century poets Randolph Henry Ash and Christabel LaMotte. Colin Dexter’s The Wench is Dead (1989) adopts a similar approach as the twentieth-century detective, Inspector Morse, engages with a nineteenth-century murder case while recovering in hospital. By contrast, in Barnes’s novel the detective figure occupies the same temporal moment as the crime and thus has direct access to the evidence. The novel replicates this situation by immersing the reader in the nineteenth-century world the protagonists occupy: historical documents relating to the crime are incorporated into the novel and many events are narrated directly to the reader. Although this seems to hold out the possibility of unmediated access to the past, the novel acknowledges the difficulty of accessing evidence and questions the nature of evidence.

As both the creator of the most rational detective in fictional history and an ardent believer in spiritualism, Arthur Conan Doyle, the “Arthur” of the title, proves an interesting figure through whom to consider what the summary on the back cover terms “the fateful differences between what we believe, what we know and what we can prove.” During the nineteenth century, there was a pervasive shift in attitudes towards evidence. As Scott McCracken argues, the detective novel appeared “at a time when the collection of evidence and the presentation of a case were replacing the extraction of a confession by torture” (p. 51). Barnes’s novel traces the complex interrelations between knowledge and belief by examining both in relation to the theme of perception. Knowledge and belief appear to operate very differently in relation to perception; whereas knowledge is often grounded in objective, empirical observation, belief is frequently dismissed as “blind faith.” While its affinity with the detective genre might suggest that knowledge is prioritised, Arthur & George reveals the impact that both modes of discourse had on George Edalji’s case.

Empirical Evidence

The case surrounding George Edalji reveals the impossibility of separating out belief and knowledge. Discounting the evidence of his own experience, George “believed, and […] still believe[s]” that “the process of the law will, in the end, deliver justice” (296). Despite his seemingly blind faith in the processes of the law, George refuses to accept the possibility that belief plays a role in his case, trusting instead to the accumulation of rational, objective, empirical evidence. Mr Meek, George’s solicitor, draws out the conflict between knowledge and belief within the judicial process. In response to George’s lament that his “parents were not good witnesses,” Mr Meek replies that “[f]rom a purely legal point of view, the best witnesses are those whom the jury believes the most” (193). George’s failure to grasp the impact of belief in his case is most evident in his assertion that “I do not believe that race prejudice has anything to do with my case” since there is no “evidence” to support that view (300). Requiring evidence before he is willing to believe in something, George here betrays his training as a lawyer, yet, as Arthur replies, “[t]he fact that no evidence of a phenomenon can be adduced does not mean that it does not exist” (301).

Despite this assertion, Arthur’s approach to detection is grounded in his confidence in observable fact. This approach is clearly indebted to the Holmesian method of “deductive reasoning,” which relies on empirical observation of the minute details of the world. Using the clues he observes, Holmes makes rational deductions about the crimes, suspects, and sometimes even the victims he encounters. The Holmesian method of detection brings together perception and knowledge; as Stephen Knight observes “[Holmes] has a knowledge of what certain phenomena will mean, and is practising deduction, that is drawing from a set of existent theories to explain new events” (86). Similarly, Arthur’s case to clear George’s name is built on a combination of observed evidence and pre-existing knowledge. In the course of his investigations, Arthur seeks to establish a direct connection with the past crimes by visiting the locale and meeting the people associated with George and his case. His desire for empirical evidence is most evident when he literally walks in George’s footsteps, timing how long it takes for himself and Woodie, his secretary, to trace the route George is supposed to have taken after one of the rippings. Interestingly, however, Arthur does not replicate the conditions of George’s supposed journey, which presumably occurred in the middle of the night; rather, using a combination of his own experience and his knowledge of George, he deduces that it would have taken George longer than the “Eighteen and a half minutes” it took him and Woodie to traverse the field (324).

Appropriately, the dual role that knowledge and perception play in George’s case is most apparent in relation to George’s eyesight, which Arthur sees as the key to the whole case. When he first goes to meet George, Arthur observes him from a distance and notes that he “holds the paper preternaturally close, and also a touch sideways, setting his head at an angle to the page” (294). He concludes that George has “Myopia, possibly of quite a high degree. And who knows, perhaps a touch of astigmatism too” (294). It is this diagnosis, which George confirms by producing the spectacles he generally forgets to wear, that confirm Arthur’s initial belief that George is innocent of the crimes for which he had been found guilty. As a “former ophthalmologist” (294), Arthur concludes that George’s eyesight is so bad that he could not have committed the crimes, all of which took place at night. Referring to Arthur as “Dr Doyle,” the narrative at this point emphasizes the scientific knowledge which underpins these observations (293). More importantly, Arthur suggests that sight provides not only the proof of George’s innocence but also the clue to why he was wrongfully convicted. Arthur notes the “false moral inferences the general public is inclined to draw from ocular singularity” and implies that this at least partly explains why George was convicted of the crimes (294). Based on his empirical observations, and above all his diagnosis of George’s vision, Arthur concludes the meeting with the declaration: “No, I do not think you are innocent. No, I do not believe you are innocent. I know you are innocent” (306). Arthur sets up a clear distinction between thinking, believing, and knowing something, and the increasingly assertive tone reveals that it is knowledge which is above all prioritised. While “thinking” and “believing” imply an element of speculation and faith respectively, “knowing” is aligned with fact, which is clearly grounded in perception. Unsurprisingly, then, it is knowledge that the detective aims for. George’s eyesight not only provides the knowledge of his innocence, to those who know how to “interpret” the evidence correctly, but also reveals how belief in his guilt occurred.

In nineteenth-century detective fiction, it is frequently the amateur detective who is revealed to be best placed to interpret the evidence of crimes, and, indeed, Arthur & George recalls this approach in pitting an amateur detective, Arthur, against the official police force and judicial system. In the detective fictions that made his name, Conan Doyle created an amateur detective whose ability to perceive and interpret the clues in the world far outstripped that of the professionals. Barnes’s novel, however, does not follow the conventional depiction of the official police force as incompetent; indeed, Captain Anson’s concern with “the how and the when and the what” aligns him with Holmes’s own rationalist approach to detection (125). Although he shares with Arthur a commitment to evidence, based on perception, Anson recognises the limitations of knowledge. When Arthur visits Anson to present his theory of George’s innocence, he asks “What, in your opinion, really happened?,” to which Anson replies: “That, I’m afraid, is a question from detective fiction. It is what your readers beg, and what you so winningly provide. Tell us what really happened” (p. 381). Anson goes on to explain that most crimes happen without witnesses and so the possibility of knowing what really happened slips out of reach. Rather, he accepts the limitations of knowledge, commenting that “[w]hat we know, what we end up knowing, is – enough to secure a conviction” (p. 382). In these comments, Anson not only suggests that there are limitations to knowledge, but also implies that the idea of complete knowledge is itself a fiction. Such comments seem at odds with the image of the Victorian era as a time of fixed and stable belief systems and confidence in the ability to know and categorise both the present and the past. Rather, they seem closer to postmodern ideas about the inaccessibility of the past and the fictional nature of totalizing knowledge systems.

However, as I have suggested, the process of trying cases on the grounds of objective evidence, rather than a subjective confession, was a relatively new one in the nineteenth century and thus the status of knowledge in legal discourses was still in flux. The fraught position of scientific evidence in nineteenth-century courtrooms is elaborated on in the novel by Dr Butter, the police surgeon whose evidence originally helped to convict George. Dr Butter laments how his evidence is distanced from knowledge and is instead aligned with opinion: “I state what I have observed – what I know – and find myself being told disdainfully that this is merely what I happen to think” (356). It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the evidence regarding George’s vision, which Arthur considers as unequivocal proof of George’s innocence, is barely mentioned in the Home Office report into George’s conviction. Indeed, George’s free pardon is achieved more as a result of the “great deal of noise” that Arthur makes than the evidence he accumulates (305). In revealing the intersections between knowledge and belief, fact and opinion, the novel demonstrates that there is not necessarily a direct and transparent connection between knowledge, evidence, and justice. However, this does not foreclose the possibility of achieving justice for the past. Rather, the novel asserts a sense of responsibility towards the past which works within the evidence available, but is not necessarily limited by it.

Anson’s approach provides an analogue for the position of neo-Victorian fiction, which combines a postmodern awareness of the limitations of evidence about the past with a commitment to working within those limitations to revive the Victorian past in the present. In much postmodern historical fiction the recognition that evidence about the past ultimately remains inaccessible leads to a playful attitude that embraces the fictional nature of all engagements with the past. Although neo-Victorian fictions similarly acknowledge that we may never uncover complete evidence about what happened in the past, their fictional engagements with the Victorian past remain rooted in the evidence that is available. These fictions share both a confident belief in the possibility of accessing the past and the sense of a responsibility to revive the past in the present. The neo-Victorian novelist, then, does not so much invent the past as work within the gaps of known history. Barnes adopts this approach when he provides a narrative account of the first horse-maiming, an event “without witnesses” (381). Although the narrative voice shifts from the limited first-person perspectives of Arthur and George to that of a seemingly omniscient narrator, it still refuses to resolve the mystery surrounding the Great Wryley Outrages by leaving the identity of the perpetrator a mystery. In this regard, Barnes respects the limits of historical knowledge since there is no historical evidence identifying the criminal.

In refusing a neat resolution to the historical crime, Barnes also realigns the priorities of detective fiction, which often emphasizes the importance of solving the crime over the concerns of justice. In several of the Holmes stories there is a sense that official justice is less important than the knowledge of who committed the crime and how. It is almost as if Holmes views crime aesthetically; he is motivated less by the idea of social justice than by the idea of completion and neatness in the resolution. For example, in “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle” (1892) Holmes allows the criminal to escape justice once he has received the confession that satisfies his inquiring mind, despite the fact that an innocent person is being held under suspicion of committing the crime. Arthur’s involvement in George’s case appears to be motivated by a similar desire for completeness; he is not satisfied with proving that George could not have committed the crimes, but is eager to establish the identity of the real criminal. Understandably, George is less concerned with identifying the “real” criminal than with clearing his name. Indeed, when Arthur presents his case against Royden Sharp, George reflects that it “strangely resembled the Staffordshire Constabulary’s case against himself” (425). George notes that Arthur’s case recalls the “brilliant acts of deduction” of Sherlock Holmes, yet this fictional creation “had never once been obliged to stand in the witness box and have his suppositions and intuitions and immaculate theories ground to very fine dust over a period of several hours” (426). Here again, evidence undergoes a transformation from knowledge to theory, recalling the process that Dr Butter laments. As Marjorie Kehe notes in her review of the novel, then, “Barnes gently mocks the Holmesian belief that life is a problem to be solved by logic and close observation. Instead, the story suggests, human justice can never be more than approximate because ‘truth’ - always filtered through one individual consciousness or another - is so fluid a commodity.” Arthur & George thus recognises that justice is not always directly connected to evidence. Despite its connections to the rational, empirical model of detective fiction, the novel is at least as much concerned with the processes of justice as it is with the issue of evidence; perhaps more so since the failure of justice is shown to have real effects on the lives of George and his family. Moreover, the novel reveals that acting responsibly towards the past involves more than just an objective, evidential approach.

“The eyes of faith”

The possibility of establishing a connection with the past that is not limited by objective ideals of evidence is explored through the position of spiritualism in the novel. While spiritualism is a common theme in neo-Victorian fiction, it seems incongruous with the detective genre and its emphasis on rationality. The practice of spiritualism, which promises to answer the mystery of what happens after death, initially seems to be juxtaposed with detective fiction, which is limited by the requirement for empirical evidence. Arthur’s approach to spiritualism, however, recalls his “detective” process; he is careful to temper his desire for knowledge with a healthy scepticism which asks “what was the minimum, not the maximum, that could be deduced?” (55). Despite this scepticism, Arthur believes that with a sufficient accumulation of facts, it is possible to confidently know the truth about what happens after death. This combination of scepticism and belief is in part due to the fraught position spiritualism occupies in relation to the issue of evidence. Arthur’s earlier assertion that “[t]he fact that no evidence of a phenomenon can be adduced does not mean that it does not exist,” can be read as a justification for spiritualism (301).

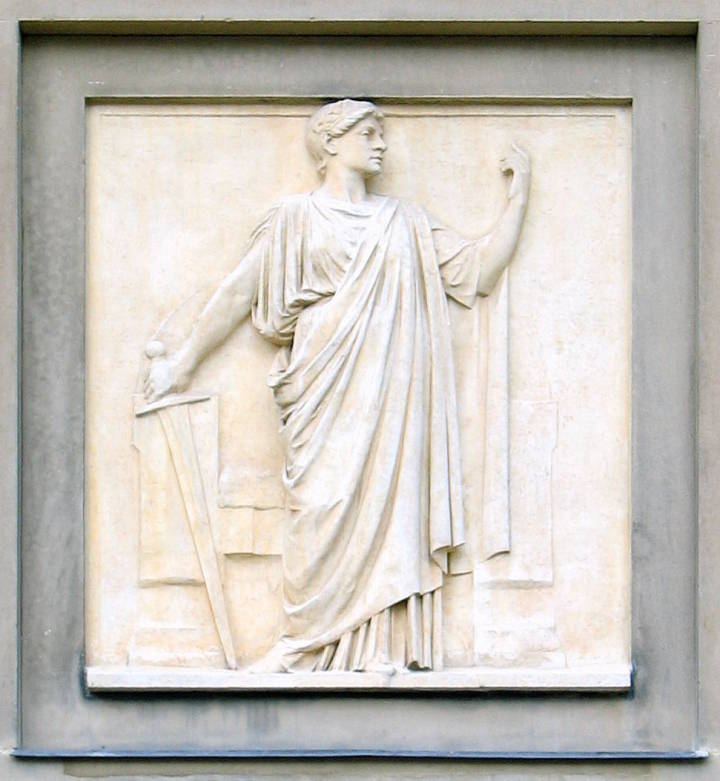

Five late-Victorian representations of justice with and without a blindfold — Left to right: (a) Sir W. Hamo Thornycrof's Justice on the Institute for Chartered Accountants Building. (b) Alfred Drury's Justice on the New War Office Building. (c) William Silver Frith's Justice on the former Metropolitan Life Assurance building. (d) Thomas Stirling Lee's Justice, able to stand alone, administers by the Sword on St. George's Hall, Liverpool. (e) William Calder Marshal's Justice on the entrance to Middle Temple Lane. Only the first and third have the familiar blindfolds. — George P. Landow.

The idea of evidence, particularly perceptual evidence, and its relationship to the disparate realms of justice and spiritualism are highlighted in the final scenes of the novel when George attends a public spiritualist meeting at which it is hoped Arthur will manifest. Arriving at the Royal Albert Hall several hours early, George spends his time practising with the binoculars that he has brought along to counteract his poor eyesight. He focuses in and out on the details of the Albert Memorial, settling on a figure that “he recognized, standing on a corner pedestal: she had a sword in one hand, and a pair of scales in the other” (476). The figure is clearly that of Lady Justice who, George is “pleased to note,” is not represented as blindfolded (476). The narrator remarks that the customary depiction of Justice as blind “had often drawn [George’s] disapproval: not because he didn’t understand its significance, but because others failed to” (476). Despite his earlier faith in the processes of justice, the narrative implicitly distances George from the concept of “blind faith” here. Indeed, as has been seen, George has come to recognise that the process of justice is not guaranteed by evidence. This sceptical attitude provides an important context for George’s subsequent experience during the spiritualist meeting, which emphasizes the difficulty of applying standard notions of evidence to spiritualist phenomena. Because of his poor eyesight, George uses binoculars to try and see the stage, prompting another member of the audience to explain to him “You cannot see him that way. […] You will only see him with the eyes of faith” (499). George remains sceptical to the events he witnesses; “He does not know whether he has seen truth, lies, or a mixture of both” (500). The culmination of the meeting, in which the medium transmits a message from Arthur to his widow, is drowned out for George, and the rest of the audience, by an organ. Despite previous displays of omniscience, the narrator does not allow the reader to overhear the spiritualist’s message. The narrative voice thus refuses to pass judgement on the veracity of spiritualism, instead maintaining an attitude that combines scepticism and belief concerning “the space where Sir Arthur has, just possibly, been” (501). This moment recalls the earlier moment in which the narrative veers towards omniscience in depicting a horse ripping, and yet pulls back from that omniscience by refusing to identity the criminal. In this regard, the novel seems to establish a connection between our ability to know the past and our ability to know the future.

Although the novel does not necessarily endorse spiritualism, in ending with a series of questions about George’s experience at the spiritualist meeting, it holds out the possibility that spiritualism can provide a way to connect with the past. The novel suggests that a responsible approach to the past needs to be sensitive to both the emotional and evidential dimensions of the past. Although George’s innocence is never unequivocally proven, in that no-one else is convicted of the crimes, he is able to return to his desired life as a solicitor. And, while his name remains merely “a footnote in legal history” (443), Barnes’s novel vividly recreates the lived reality of his experiences. Moreover, Arthur & George implicitly reveals how the past can impact on the present by drawing out the repercussions George’s case had on the English judicial system, specifically in highlighting the need for a Court of Appeals.

Bibliography

Barnes, Julian. Arthur & George. London: Vintage, 2005.

Kehe, Marjorie. “How would Sherlock Holmes fare in real life?” The Christian Science Monitor 17 Jan 2006.

Knight, Stephen. Form and Ideology in Crime Fiction. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1980.

McCracken, Scott. Pulp: Reading Popular Fiction. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Last modified 26 August 2011