“We are all socialists now.” — Sir William Harcourt

Introduction

ictorian socialism — or Victorian socialisms because it took so many different gradations —, emerged in Britain along with other movements, such as new conservatism, new liberalism, new trade unionism, anarchism, social Darwinism, secularism, spiritualism and theosophy. It developed from diverse traditions, ideologies and backgrounds, but intense dislike of the social effects of the Industrial Revolution underlie the various strands of Victorian socialism, which was essentially a middle-class, home-made project with little foreign influence.

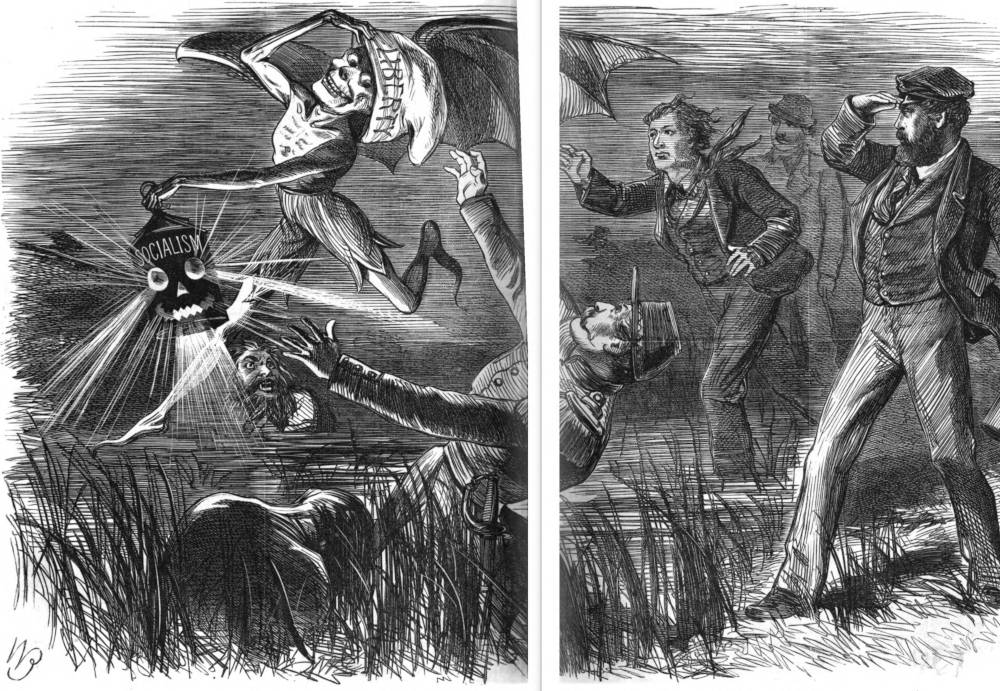

An attack on French socialism by William Henry Boucher, editorial cartoonist for the 1871 Judy, or the London Serio-Comic Journal, a conservative rival to Punch.

Victorian socialists drew heavily not on the works of Karl Marx, but on the legacy of authors who held romantic, radical and even conservative views, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Cobbett, Thomas Carlyle, Benjamin Disraeli, and John Ruskin. However, the roots of British socialism can also be sought in more remote times. Some of the distant forerunners of Victorian socialism include William Langland, John Wycliffe, John Ball, Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Gerrard Winstanley, and James Harrington.

Origins of British socialism

British socialism emerged in the time when Victorian society began to overcome the principles of classical economics, the laissez-faire system, and was immersed in faith crisis. Traditional British liberalism and radicalism played a far more important role in shaping socialism in Victorian Britain than the works of Karl Marx. Although Marxism had some impact in Britain, it was far less significant than in many other European countries, with thinkers such as David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill and John Ruskin having much greater influence. Non-Marxist historians speculate that this was because Britain was amongst the most democratic countries of Europe of the period, where the ballot box provided an instrument for change, so parliamentary reforms seemed a more promising route than revolutionary socialism advocated by Marx. As Sir Ivor Jeggins put it, “British socialism has always been as much British as socialist.” (429)

Socialist ideas became the natural outcome of modern industrial conditions, and their origins can be sought in the beginnings of modern industry. In England socialist ideas were shaped as the by-product of the Industrial Revolution. The word 'socialism' was first used in the English language in 1827 in the working-class publication, the Co-operative Magazine, and it meant co-operation as opposed to competition. (Garner et al. 115) In the 1830s, the word socialism was used interchangeably with the word Owenism, and Robert Owen (1771-1858) became the central figure of British socialism in the first half of the 19th century.

The rise of working-class radicalism

The first political movement of the working-class was launched by the London Corresponding Society, founded in 1792, by Thomas Hardy (1752-1832), a shoemaker and metropolitan Radical. The Society, consisting mostly of working-class members, agitated among the masses parliamentary reform, universal manhood suffrage and working class representation in Parliament. The Society met openly for six years despite harassment by police magistrates and arrests of its members, but was finally outlawed in 1799 by an act of Parliament as a result of fear that it made a dangerous challenge to the established government.

Robert Owen and co-operative socialism

Robert Owen (1771-1858), who was a textile mill owner, philanthropist, social and labour reformer, is considered as the father of British co-operative socialism. He and his followers founded several co-operative communities in Britain and the United States which offered workers decent living conditions and access to education. Although all Owenite communities eventually failed, the communitarian tradition persisted in Victorian England and elsewhere. Owenism exerted a significant influence on various strands of British socialism, including Christian socialism, ethical socialism, guild socialism, Fabianism, and socialist labour movement. Co-operative socialism was perceived by these organisations as a replacement for the unjust competitive capitalist system.

Ricardian socialists

Another group of thinkers who exerted a direct influence on Victorian socialism were so called Ricardian socialists. They based their theories upon the work of the economist David Ricardo (1772-1823), who claimed that the economy moves towards social conflict because the interests of ownership classes were directly opposed to those of the poor classes. In this aspect Ricardo and Ricardian socialists anticipated the conception of Karl Marx about adversarial class relations.

The principal members of this group were Charles Hall (1740-1820), William Thompson (1785-1833), Thomas Hodgskin (1783-1869) and John Gray (1799-1883). Paradoxically, Ricardian socialists, rejected some of Ricardo's assumptions and argued that private ownership of the means of production should be supplanted by central ownership of means of production, organised as a worker-controlled joint stock company. (Toler 46)

Marxian socialism

Marxian socialism had little impact on various strands of Britain's socialism. Karl Marx (1818-83), who lived and wrote his works in London from 1849, was not widely known in England until his death. He met few Englishmen and was not very keen on making acquaintances with English radicals. The only Englishmen who expressed serious interest in the ideas of Marx during his lifetime were Ernest Jones, a revolutionary Chartist, who made a vain attempt to revive that dying Chartist movement, and Henry Mayers Hyndman, the founder of the Social Democratic Federation, the first Marxist socialist party in Britain. However, Marxism hardly appealed to Victorian socialists in its orthodox form.

Late-Victorian socialism

Socialists by William Strang R.A. (1859-1921). 1891. Etching and drypoint on paper. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The British socialist movement re-emerged in the 1880s. A strong critique of capitalism, which was voiced by various groups of social critics, literary figures and working-class militants, led to the formation of three distinct strands of late Victorian socialism: (1) the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the Socialist League, (2) the Fabian Society and its predecessor, the Fellowship of the New Life, and (3) the ethical socialists, together with the Independent Labour Party.

The Social Democratic Federation, which became the first Marxist political party in Britain in 1884, advocated imminent revolution and nationalisation. Its tiny offshot, the Socialist League, formed by William Morris in 1884 after his secession from the Social Democratic Federation, attracted a few social democrats, but in 1990 it became dominated by anarchists, which prompted Morris to withdraw from it.

The Fabian Society, also founded in 1884, was not radical, but tried to permeate peacefully the existing institutions and Parliament in order to implement its socialist reforms. The Fabians supported the so-called 'gas and water socialism', i.e. government ownership of municipal utilities, as well as municipalisation and nationalisation of land and many industries, canals, railways, water and gas companies, tramways, docks, hospitals, markets, libraries and even lodging houses. (Haggard 94)

Ethical socialism was not associated with any particular party and overlapped with other strands of Victorian socialism. It included a disparate group of social activists and literary figures who championed the ideas of ethical socialism, emphasising moral development of individuals above economic and social reforms. Ethical socialism emerged in the 1880s, flourished in the 1890s, and inspired the formation of the Independent Labour Party and also the Labour Party. (Bevir 1999: 218)

The most characteristic representatives of ethical socialism were Thomas Hill Green, Edward Carpenter, John Ruskin, and William Morris. Other important figures included the pioneer labour leader, Keir Hardie, Robert Blatchford, the editor of the weekly newspaper, The Clarion, and the author of the bestselling socialist tract, Merrie England (1893), John Bruce-Glasier, one of the leaders of the Independent Labour Party. As Mark Bevir put it, ethical socialists believed in the ideal of moral fellowship and thought of a co-operative and decentralised civil society where individuals could exercise full control of their own daily activities. (McDonald 58-59)

The land nationalisation movement

The roots of the British land nationalisation movement, which strongly influenced the mainstream tradition of late Victorian socialism, can be sought in the activity of Thomas Spence (1750-1814), a self-taught militant, who devoted most of his adult life to various forms of political agitation. In the 1770s, he argued that all land must be owned not by individuals but by parochial corporations. (Parssinnen 135) In the early 1800s Spence became the leader of a group of radicals who advocated social revolution in Britain. After his death the radical followers of Spence formed the Society of Spencean Philanthropists (1815). Its members gathered secretly in small groups in alehouses and discussed Spence's socialist agrarian plan and the best way of achieving an equal society. They also distributed tracts, pamphlets, broadsheets, posters and poems and metal tokens advertising Spence's ideas (Benchimol 153).

Land reform was one of the hottest issues among British radicals and social reformers from the 1860s until World War One. In mid-Victorian England, James Bronterre O'Brien (1805-64), a Chartist leader and working-class reformer, proposed a scheme for government purchase of land and then its redistribution by rental. (Bronstein 107) O'Brien's followers, grouped in the National Reform League, continued to propagate the idea of land nationalisation after his death in 1864. The Land and Labour League, that grew out of the National Reform League in 1869, advanced a programme that called for land nationalisation, but it made little public impact.

In late Victorian England, Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer with Charles Darwin of the theory of natural selection, revived the land nationalisation movement. Wallace believed that land should be owned by the state and leased to people. In 1881, he was elected as the first president of Land Nationalisation Society, which devised a plan of State-owned and -leased lands. Wallace's view of land reform was close to the spirit of Henry George's treatise, Progress and Poverty(1879), which promoted a single progressive tax on land values in order to reduce economic inequality.

The Land Nationalisation Society and the Social Democratic Federation gave a full support to land nationalisation programmes. The Land Restoration League and the Land Reform Union (LRU), also advocated state land appropriation. All these schemes strengthened the land nationalisation movement in late Victorian Britain and aroused an awareness for the need of land reform. Wallace's as well as George's ideas of land reform were approved by labour unions and inspired both the Liberal and Labour Parties to form a policy of land redistribution at the turn of the 19th century.

The Labour Church

The last two decades of the Victorian era also saw the emergence of the Labour Church, which was started in Manchester in 1891 by a Unitarian minister, John Trevor (1855-1930), and had a distinct socialist message. The Labour Church soon became a nationwide movement and claimed 100 churches with congregations between 200 and 500. (Worley 154) The conference held at Bradford in 1893 to form the Independent Labour Party was accompanied by a Labour Church service which was attended by 5,000 people. However, the Labour Church movement began to fade after 1900. At the annual conference of 1909, held in Ashton-under-Lyne, the name Labour Church was changed to Socialist Church, but by the beginning of World War I the recently renamed Labour Church had disappeared.

Conclusion

The term socialism was generally synonymous in Victorian Britain with social reform, collectivism, communitarianism and improvement of living conditions of the working class and it did not bear strong Marxist connotations. In fact, few people were interested in socialist revolution in Victorian Britain, but quite a great number were fascinated by the mystical features of socialism. Unlike Marxism, which criticised liberal democracy and advocated revolutionary class struggle, the main strands of Victorian socialism can be characterised by ethical, non-Marxian, anti-capitalist outlook which combined traditional English radicalism with traditional English respect for democracy.

References and Further Reading

Beer, M. A History of British Socialism. London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1919.

Benchimol, Alex. Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2010.

Berlin, Isaiah. Karl Marx: His Life and Environment. New York: Time, 1963.

Bevir, Mark. The Making of British Socialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

_____. “The Labour Church Movement, 1891-1902,” Journal of British Studies, 38(2) 1999, 217-245.

Britain, Ian. Fabianism and Culture: A Study of British Socialism and the Arts 1884-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Bronstein, Jamie L. Land Reform and Working-class Experience in Britain and the United States, 1800-1862. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Carter, M. T. H. Green and the Development of Ethical Socialism. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic, 2003.

Christensen, Torben. The Origin and History of Christian Socialism, 1848-54. Aarhus: Universitetsforlaget, 1962.

Claeys, Gregory. Machinery, Money, and the Millennium: From Moral Economy to Socialism, 1815–60. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987.

____. Citizens and Saints: Politics and Anti-politics in Early British Socialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Claeys, Gregory, ed. Owenite Socialism. Pamphlets and Correspondence: 1832-1837. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Cole, Margaret. The Story of Fabian Socialism. London: Heinemann, 1961.

Ely, Richard T. Socialism: An Examination of Its Nature, Its Strength and Its Weakness, with Suggestions for Social Reform. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1894.

Fremantle, Anne. This Little Band of Prophets: The Story of the Gentle Fabians. London: Allen & Unwin, 1960.

Garner, Robert, Peter Ferdinand, Stephanie Lawson. Introduction to Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Haggard, Robert F. The Persistence of Victorian Liberalism: The Politics of Social Reform in Britain, 1870-1900. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001.

Himmelfarb, Gertrude. Poverty and Compassion: The Moral Imagination of the Late Victorians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1991.

Hobsbawm, E. J. Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959.

Hyndmann, H. M. The Historical Basis of Socialism in England. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co., 1883.

Inglis, Kenneth S. Churches and the Working Classes in Victorian England. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963.

Jennings, Ivor. Party Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Lawrence, J. “Popular Radicalism and the Socialist Revival in Britain,” Journal of British Studies, 31 (1992) 163-86.

McBriar, Alan M. Fabian Socialism and English Politics 1884-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Mackenzie, Norman, and Jeanne Mackenzie. The First Fabians. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977.

Mc Donald, Andrew, ed. Reinventing Britain: Constitutional Change Under New Labour. University of California Press, 2007.

Manton, Kevin. “The Fellowship of the New Life: English Ethical Socialism Reconsidered,” History of Political Thought, 24(2) 2003, 282–304.

Milburn, Josephine Fishel. “The Fabian Society and the British Labour Party,” The Western Political Quarterly, 11(2), 1958, 319-339.

Norman, Edward. The Victorian Christian Socialists. Cambrige: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Parssinnen, T. M. “Thomas Spence and the Origins of English Land Nationalization,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 34(1) 1973, 135-141.

Pease, Edward R. The History of the Fabian Society. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company Publishers, 1916.

Raven, Charles E. Christian Socialism, 1848-1854. 1920. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, Publishers, 1968.

Shaw, George Bernard, ed. Fabian Essays in Socialism. London: Fabian Society, 1889.

____. The Fabian Society: Its Early History. London: Fabian Society, 1892.

Thompson, E. The Making of the English Working Class. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

Toler, Pamela. The Everything Guide to Understanding Socialism: The Political, Social, and Economic Concepts Behind this Complex Theory. Avon, MA: Everything Books, 2011.

Ward, P. Red Flag and Union Jack: Englishness, Patriotism and the British Left, 1881–1924. Woodbridge, UK: Royal Historical Society, 1998.

Waters, C. British Socialists and the Politics of Popular Culture 1884-1914. Manchester: Manchester Univerrsity Press, 1990.

Webb, Sidney and Beatrice Webb. A Constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920.

___. Industrial Democracy. London: Longman, 1897.

White, R. E. O. Christian Ethics. Leominster, Herefordshire: Gracewing Publishing, 1994.

Worley, Matthew, ed. The Foundations of the British Labour Party: Identities, Cultures and Perspectives, 1900-39. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009.

Yeo, S. “A New Life: The Religion of Socialism in Britain, 1883– 1896,” History Workshop, 4 (1977) 5-56.

Last modified 10 March 2015