In the The Victorian Church Owen Chadwick compares the ineffectual evangelical Archbishop of Canterbury J. B. Sumner to Shaftesbury, the “senior evangelical layman. The Earl of Shaftesbury had qualities which Sumner lacked; courage, decision, prominence, toughness. If Shaftesbury had driven in Sumner’s seat, the ancient coach of the Church of England might have ended its friendly lumbering journey in a smash” (454).

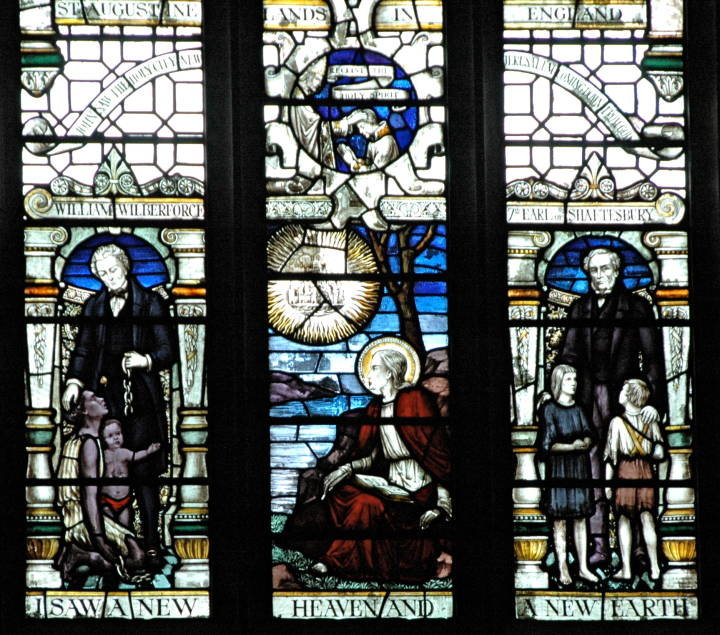

Memorials to Lord Shaftesbury: Left: I saw a new heaven and a new earth. Christ Church, Chelsea. 1929. Designer: Archibald Keightley Nicholson (1871-1937). Wilberforce and Lord Shaftesbury flank St. John and his vision of a new Jerusalem in this lower portion of the west window. Right: Eros (Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain) by Sir Alfred Gilbert, R. A. (1854-1934). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

haftesbury was the noblest philanthropist of the century. He promoted more good causes, and was therefore more cordially disliked, than any other politician of the Victorian age. He poked his long and charitable nose into sewers of London and hovels of Dorset, mills of Manchester and mines of Durham; enquired into children in factories or up chimneys, lunatics in asylums, milliners and needlewomen, burglars and pickpockets; attended tea-meetings in schools, read lessons from the Bible at services in theatres, encouraged the movement for ragged schools to educate the urchins of east London. When he succeeded his father as earl and inherited estates encumbered with a crushing tonnage of debt he signified his arrival at the little Dorsetshire village by closing the tap-room at 9 p.m., hiring a scripture-reader for the outlying hamlets, redecorating the village church, starting three schools and several new cottages, and arranging cricket matches in his park. He hardly read a book but the Bible. To read other books he had no time; writing hundreds of letters in his own hand, presiding at meetings of godly and philanthropic societies, devising bills for the Commons or the Lords, vainly urging policies upon ministers of state, never concealing his mind. He once talked proudly or wearily of meetings by day and by night on every imaginable subject. His stature was national; partly because working men knew that for all his aristocratic conservatism he was their friend, partly because his unbending consistency gained the rueful respect of gentlemen who saw more clearly the need to compromise, and partly because he spoke for evangelical religion in an age when evangelical religion seemed suddenly to be the most potent religious and moral force in England. Cabinet ministers liked the idea of having him publicly on their side provided that he was given no post with power to act.

The death of the Reverend Edward Bickersteth in 1850 was disaster to Shaftesbury. Bickersteth was his private counsellor. A man of apocalyptic hope and puritan conduct, Bickersteth possessed an enchanting humane godliness and little interest in ecclesiastical politics. . . . Five years later a lay Scotsman took Bickersteth’s place in his cabinet counsels: Alexander Haldane, proprietor and leading writer of the Record. For thirty years Shaftesbury came into almost daily communication with Haldane. The exchange of Bickersteth for Haldane was not a blessing. Haldane encouraged the less agreeable side of Shaftesbury’s evangelical faith — clamour for evangelical truth or puritan morals, concern for ecclesiastical politics and appointments, innate anticlericalism and antipopery, gaunt pessimism about church and Christian society. An air of harshness surrounded Shaftesbury as he walked and talked. A kindly preacher once directed a sermon against gloom to his personal pew. Inside he was a simple person with a clear head, a troubled conscience, and a few fixed ideas of evangelical religion. But as the years passed the childlike quality became harder to discover behind the precise mouth and cold passionless eyes of a marble public face. Age did not ossify his mind, for it was ossified before he was old. Nor did it dry his emotions, for they remained as charged and hot as ever. But he poured torment of soul into his diary, spreading it out like Hezekiah in the Temple, and let no one see but posterity.

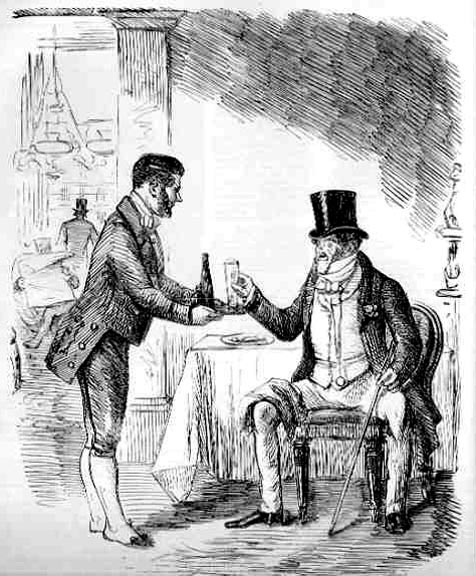

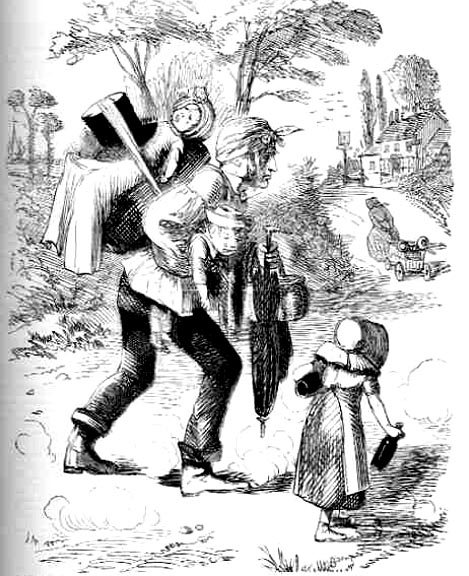

Three cartoons from Punch: Hypocrisy denouncing music and Sunday Finery?. Sunday Music as Cant Would Have it. Circumstances Alter Cases. Click on thumbnails for larger images.

Shaftesbury believed that the laws of England should conform to the laws of God; and the law of God ordered no man to work on the Sabbath day. With perfect consistency he stumped platforms and campaigned in Parliament for a godly Sunday as he campaigned for shorter hours or slum education. And evangelicals who pleaded the Sabbath encountered more obloquy than other evangelicals. For success—that is, compelling Englishmen to keep their Sabbath willy-nilly—meant inconvenience and discomfort and gloom for everyone; but especially for the poor. If no one was allowed to work on Sunday, no bus-drivers nor pilots of pleasure steamers nor park-keepers nor musicians nor stokers, the only occupation left to the poor of the London slums was drinking gin; an occupation which they pursued with zeal, and consequences far from Sabbatarian.

to large meetings in Hyde Park and elsewhere, followed by riots. The Bill was subsequently repealed.“ Punch did its part to fan the flames.

Punch on the class implications of a law prohibited the sale of beer on Sundays, each “Dedicated to my Lord Robert Grosvenor”: Club. The Roadside Inn (I). The Roadside Inn (II).

Bibliography

Chadwick, Owen. The Victorian Church. London: Adam & Charles Black. 1966.

Last modified 19 June 2018