[The following passage from the Chambers 1838 Gazetteer of Scotland appears on page 479. — George P. Landow.]

ames VI. died at London, on the 27th of March 1625, without having again visited his Scottish dominions, and, on the subsequent Sunday, the ministers of Edinburgh preached his funeral sermon, in which they praised him as the most religious and peaceable prince that this unworthy world had ever possessed. Charles I. was proclaimed at the Cross, on the 31st of March 1625, at which time, the town-council agreed to advance to the new king the assessment of the city, and to contribute to the maintenance of ten thousand men, at the same time providing for the city guard, and for the discipline of the whole citizens.

As early as 1628, Charles agreed to visit the ancient city of Edinburgh, for the purpose of being crowned king of Scots, but it was not till some years later that he was able to proceed thither. On the twelfth of June 1633, he entered the town by the West Port, where he was received with the same pomp, and the same extravagantly flattering oratory, which had been exhibited at the reception of his royal father. On the eighteenth, Charles was crowned in the abbey church of Holyrood, with unwonted splendour, and two days after, he assembled his first parliament of Scotland in the tolbooth, in which the acts concerning religion were confirmed, and the authority of the college of justice, the privileges of the royal burghs, azid the rights of the whole people ratified. While Charles remained in Edinburgh, the nation exhibited a universal joy, but he had hardly returned to London, when numerous discontents arose. One of the most important acts of Charles during his residence, was the erection of the bishopric of Edinburgh, a measure, which, in 1637, was followed up by orders to use a liturgy in the already constituted Episcopal church. The tumults which ensued in Edinburgh, on the attempt being made to introduce the service-book in the church of St. Giles, are so much connected with general history that they need not be here particularized. The ill-advised measures of Charles produced a General Assembly, which sat at Glasgow in 1638, and at once restored Presbyterianism in all its forms of worship and church government. A pacification having taken place at Berwick betwixt the king and his Scottish subjects, the castle of Edinburgh was delivered to the Marquis of Hamilton for the king's interest, and strengthened, in case of future disturbances, by the arms and ammunition from the fortifications of Leith, which for this purpose were demolished.

Cowfeeder Row and Head of West Port from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh. Click on image to enlarge it.

In 1640, a fresh war broke out between the king and his Scottish subjects, the latter being now considerably emboldened by assurances of countenance and support from the English malcontents. The magistrates of Edinburgh, on this occasion, caused the town to be fortified against the castle, and exercised the citizens in arms. Such demonstrations of a warlike nature caused the governor to fire upon the city, but the fort being invested by Lesly, its inmates were finally obliged, for want of provisions, to make an honourable surrender. The treaty of Rippon put a stop to further mischief at this time, and in 1641, the unhappy Charles, to quiet the discontents of his northern subjects, again visited the ancient metropolis of Scotland. The measures he adopted, while in the city, were singularly improper. Like many sovereigns in difficulties, he tried to purchase security by rewarding his enemies and leaving his friends to be prosecuted, or in a state of neglect, a procedure which was attended with the worst effects. Charles was, however, graciously received by the magistrates and was sumptuously entertained at an expense of £12,000 Scots. In the contentions of the few following years, during which the Scottish and English people united in a war against the king, Edinburgh was the scene of the chief political and diplomatic transactions of the nation, particularly the construction of the Solemn League and Covenant between the two nations, for the extirpation of prelacy and other unpopular objects, which was signed in the High Church, July 1643. In the army which Scotland sent, in consequence of this treaty, to assist the English parliamentary forces against Charles, one regiment of twelve hundred men was raised and supported by Edinburgh, at a cost of £60,000 Scottish money.

In 1645, the Marquis of Montrose, in the course of his campaign in favour of the king, threatened Edinburgh with his desolating army, but was prevented from entering it by a common enemy having previously taken possession — namely, the plague — which now, for the last time, had visited the city. "For aught I can learn," says Maitland, "Edinburgh never was in a more miserable and melancholy situation than at present; for by the unparalleled ravages committed by the plague, it was spoiled of its inhabitants to such a degree, that there were scarce sixty men left, capable of assisting in defence of the town in case of an attack; which the citizens had never more occasion to fear than at this time, for the army of the Covenanters being routed at Kilsyth by the Marquis of Montrose, that intrepid royalist sent a letter to the magistrates, demanding the instant freedom of all prisoners belonging to the king's party within the town, under penalty of the city being visited by fire and sword, which peremptory order occasioning great confusion in Edinburgh, the common council assembled in order to deliberate thereon, .And having considered the dismal situation of their affairs, by the defeat of their army at Kilsyth, the miserable and fenceless state to which their city and castle were" reduced by pestilence and famine, the inability of their friends to assist them, the great riches in the town of Edinburgh, which could not be removed because of the plague, the national magazine of military stores, and the records of the kingdom, together with the great number of state and other prisorfers in the town's prison, who, becoming desperate for want of money and provisions (little or none of the last being brought to the city by reason of the pestilence,) threatened to kill their keepers, to favour their escape, and prevent their being starved. These things being duly considered, the citizens thought fit to comply with Montrose's demands." The sufferings of Edinburgh at this period of its history would seem to have had the effect of banishing even moral principles from the minds of the citizens. Having borrowed £40,000 Scots, in order to raise some troops they had promised to furnish in the national Engagement in favour of Charles, they afterwards endeavoured to avoid this debt, under the pretence that it was contracted in an unlawful cause. They consulted the Assembly of Divines, who supported their scruples, on the pretext that the money had been borrowed for an uncovenanted purpose! Being thus backed, they refused to pay their creditors, till Cromwell's authoritative tribunals, in 1652, obliged the magistrates to make an immediate settlement. Every historian of Edinburgh speaks with indignation of the conduct of the magistrates and clergy in this transaction; though a philanthropic writer of the present time will only see in it the lamentable effect of extreme party spirit, whether in religion or politics, in sophisticating the moral principles.

The year 1650 was long remembered in Edinburgh for the events which occurred in it. On the 18th of May, the Marquis of Montrose was brought a prisoner into the city, by way of the Canongate, along which he was carried with an ignominious pomp significant of his fate. In three days after, he was brought before the parliament for trial, and being condemned to death, he suffered on the gallows at the Cross with that fortitude which had distinguished his character.

Left: The Castle from the Vennell. Right: The Castle from a Window in George IV Bridge. Both by Hanslip Fletcher. 1910. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Being averse to submit to the republican government established in Britain, the Scots, without calculation, invited the exiled Charles II. to be their king, who, agreeing to their wishes, was proclaimed, at the Cross, on the 15th of July. To frustrate arrangements of this kind, Cromwell and his army crossed the Tweed on the 22d of the same month, and marching by Haddington, towards Edinburgh, encamped near Pentland hills, within a few miles of the city, while the Scots, under the command of Lesly, entrenched themselves in a fortified camp between Edinburgh and Leith, on the ground now occupied by the road called Leith-Walk, which took its form from the entrenchments then cast up.

Leith Walk. Hanslip Fkletcher. 1910. Click on image to enlarge it.

Cromwell, finding his enterprise to be hopeless, returned first to Musselburgh, and afterwards to Dunbar. Here the Scottish forces were encountered and defeated by his army of saints, on the 3d of September: after which, again advancing westwards, he seized Leith, the city of Edinburgh, and the fortlets of Borthwick and Roslin. His troops also invested the castle of Edinburgh, which yielded by capitulation in the month of December. While the city was thrown into confusion by these calamities, it was deserted by the magistracy, who fled to the new head-quarters of the king and the forces at Stirling; and from the 2d of September, till the 5th of December 1651, the metropolis had no other civic rulers than a body of thirty respectable citizens chosen by the inhabitants to preserve the peace of the town.

Cromwell having afterwards gained entire possession of Scotland in consequence of his victory over its army at Worcester, a body of English commissioners was sent by him to rule the kingdom, who arrived at Dalkeith, in January 1652, and so humiliated the citizens that it was found necessary to ask their consent before proceeding to elect new magistrates. Under the government of Cromwell, the city of Edinburgh and the town of Leith enjoyed some rest after their disasters and exhausting wars. In Leith many English families were induced to settle under the protection of a strong garrison kept in the citadel of the port. It is mentioned as significant of the impoverished condition of Scotland at this period, that there was hardly a person or community capable of paying their debts. The city of Edinburgh owed nearly £550,000 Scots, which being unable to satisfy on demand, the magistrates had a charge of horning for the amount served against them, and it was with difficulty the burgh procured time to liquidate the debt. During the period of the Commonwealth, scarcely any appearance of a separate kingdom remained in Scotland, and in Edinburgh the English tribunals suspended the abominable routine of state functionaries which before and afterwards disgraced the country.

When intelligence was received of the restoration of Charles, in 1660, the town-council addressed a letter to the king, in which they declared their concurrence with those who had "prudently laid themselves out" to settle the king upon the throne of his dominions. As a testimony of their loyalty they sent a present of £1000, and his Majesty, in return, gave the magistrates power to levy one-third of a penny on the pint of ale, and twopence on the pint of wine consumed in the city; for, in the words of Arnot, it has always been equally unfortunate for the inhabitants, whether the magistrates testified their loyalty or sedition; both being made pretexts for levying money from the inhabitants; the only difference lying in the name bestowed on the exaction, which, in one case, was called a tax, in the other a fine. So great was the joy, at Edinburgh, when the citizens heard of the king's arrival in England, that they caused a sumptuous banquet to be made at the Cross. Charles was much pleased with these attentions, and ratified some of their old privileges, and promised a confirmation of their several rights.

At this time the town-council granted liberty to a person called Adam Woodcock to establish a stage coach betwixt Edinburgh and Leith, the whole fare for which they ordained to be one shilling, or for a single individual, fourpence, Sterling. This is among the first notices we have of public coaches between the two towns, and the establishment of such a convenience marks the rising spirit of luxury and desire for comfort at the middle of the seventeenth century. An entry in the council books about twelve months later gives us a notion of the wretched jurisprudence of the age: the record bears to be a grant to the baron bailie of Broughton, giving to him, by way of escheat, the goods and chattels of women condemned for witchcraft.

On the 22d of August 1660, the king abolished the English tribunals in Scotland, reestablishing the ancient forms of government; and the city once more rejoiced in the presence of the officers of state, the privy council, and the parliament. The first parliament assembled on the 1st of January 1661, under Lord Middleton, in which the public transactions, during the last twenty- three years, were reprobated as unwarrantable, and accordingly rescinded. As this new law abolished the settlement of presbytery in 1638, as illegal, the episcopal church of Charles I. was consequently restored, though on a modified footing, there being no attempt to re-introduce the liturgy, or other insignia of an episcopal communion, farther than the institution of the authority of bishops. It was unfortunate for the interests of the episcopal church, that laws giving a full liberty to presbyterians were not simultaneously promulgated. The reverse of this was the case. The utmost severities were practised on those who absented themselves from the established churches, and by a course of tyrannous transactions, as infamous as they were ineffectual, the country, especially in the west, was precipitated into a state of insurrection which lasted for about twenty-seven years. Throughout this gloomy period of Scottish history, the city of Edinburgh was the scene of the trial, torture, and execution of innumerable victims of the privy council. Such sights, however, do not seem to have terrified the lower orders of the metropolis into patient submission. At the execution of one Mitchell, a person who attempted to assassinate the Archbishop of St. Andrews in the High Street, the scaffold was assailed by bands of women, who endeavoured to rescue him from the gripe of justice.

While the lower and the middling classes of Edinburgh beheld the proceedings of the privy council with contempt, and occasionally met them with resistance, the magistracy were the alternate dupes, boon companions, and instruments of oppression of the government functionaries. "To secure the good will of Lauderdale, the Scottish boroughs gave him a pension, of which, on one occasion, there were £3400, Scots, of arrears; seeing the necessity of paying this sum, the council ordered money to be borrowed on the town's account to discharge it! Not long afterwards, the corporation entertained Middleton the Commissioner, in a very elegant and sumptuous manner, at the expense of £8044, Scottish money." In these simple records, we see how the debt of the city of Edinburgh arose. There can be no doubt that these pensions and entertainments were given as bribes. Indeed, this is made quite obvious by an entry in the council register of March 14th — 15th, 1671, which bears, that the council executed a bond for £5000 to be given to the Duke of Lauderdale, to obtain from him a perpetual grant on the duties upon wine, spirits, and rum; till which time the said bond was to remain in the hands of the town clerk. The grant being obtained under the great seal, the bond was accordingly tnven up to the duke. To such nefarious practices have the citizens of Edinburgh to trace most of those vexatious burdens, which till the present hour press upon their industry and means of support. There seems to have been no end to the exactions of Lauderdale, and his ingenuity appears to have been commensurate with his rapacity. Some time before the above event, he fell upon a strange mode of frightening the metropolis into payment of a handsome sum. He procured from Charles II. (1663) a grant endowing the Citadel of Leith, under the complimentary name of Charleston, with the privileges of a free burgh of barony and regality, the office of bailiary, a weekly market, and a yearly fair, and other immunities. As Edinburgh had ever held Leith in a species of subjection, and found it an excellent source of revenue, the erection of this free burgh, which lay on the north side of the mouth of the Leith water, gave it some cause of concern. It is now understood that the whole was a trick of the Duke, whose intentions were exposed by offering " this new vamped gift" to the magistrates and town-council. Finding themselves under a necessity to enter into terms regarding the purchase of this "toy," they were offered it at the exhorbitant price of six thousand pounds, Sterling, and were actually compelled to comply with the demand. So frequent and severe were the exactions of Lauderdale, that it appears, by a computation, he received from the city funds, in nine years, no less a sum than eleven thousand pounds, Sterling, while other ministers, as well as favourites of the town council, in the same space of time, received from three to four thousand pounds of the same money. Maitland calculates, that up till the year 1680, the tewn-council of Edinburgh had expended no less than £40,000 Sterling, merely in purchasing liberty to tax the town; "to which," says he, "if we add the money of late said to have been not so well applied as it ought, it will then be found to amount to about £52,070, which is more than the town's debts are at present (1753); whereby there is, as it were, a perpetual debt entailed upon the city, which by good management, might either have been prevented, or long ere now paid off."

Agreeably to the desire of petty legislation in these times, the town-council of Edinburgh interfered to regulate the most paltry affairs of common life. At an early period of the seventeenth century, the magistrates had made laws 1 regulating the wearing of plaids by women, which having had little effect, in 1648, a new dictatorial mandate was issued, hy which all women, of whatever condition, presuming to wear plaids about their heads, in the streets, churches, or market-places, should forfeit the said plaids, and to be otherwise punished at the discretion of the magistrates; also, enjoining the town-officers and guard to seize the plaids of all offenders to their own use; and if any officers could be convicted of negligence in this delicate duty, they were to be imprisoned and deprived of their offices.

A law less offensive, but equally absurd, was passed by the council in 1677, to modify the extravagant prices charged at Penny Weddings, which, in spite of the tumults in the country, were well attended. It was ordained that no person, on these occasions, presume to take more for a man's dinner than twenty-four shillings, and from women, eighteen shillings Scots — that is two shillings, and one shilling and sixpence Sterling. The price of a carcass of mutton about this time was one shilling and fourpence Sterling, and the daily wages of a mason were nearly the same. Although laws had long before been ordained prohibiting the use of thatch on houses in Edinburgh, by another enactment in 1677, imposing fines on persons allowing thatch to continue on their houses, in consequence of the number of fires which had broken out in the town, it is ascertained that at this time, the houses in the metropolis were in many cases built of wood and covered with straw. Sumptuary laws to restrain extravagance in cases of funerals were at this time also passed, to such an injurious height had this passion of the Scots arrived. But the most serviceable legislative measure of the period was the establishment of the royal College of Physicians. Before that, the city was overrun by quacks and mountebanks, of whose pretensions and the deplorable state of the science of medicine, there is a lively instance in the records of the privy counci£ One James Michael Philo, physician, sets forth that his majesty had allowed him to practise his profession in England, and for that purpose to erect public stages; and he intreats the same liberty in this kingdom. The council, accordingly, allow him to erect a stage in the city of Edinburgh; but they also appoint the petition to be intimated to, and answered by, the Master of Eevells, against the next meeting of the council; and, in the mean time, discharge the physician to practise rope dancing.

In the year 1679, the palace of Holyroodhouse, then just finished in its present form, was made the temporary abode of James, Duke of York, who came to Edinburgh, nominally as Commissioner to the Scottish parliament, but, in reality, with the purpose of awaiting at a distance the fate of the famous Exclusion Bill, which for some time threatened to prevent his succession. It was the policy of James to draw the leading men of the kingdom around him, and to attach them firmly to his person, so that, in the event of losing England, upon the death of his brother, he might at least secure Scotland to himself. He therefore put in practice all the usual aims of those who aim at popularity; studied the prejudices and desires of the people, showed a remarkable degree of tenderness and impartiality in the distribution of justice, and encouraged every proposal for the advancement of trade. His principal aim was to foster in the nation the remembrance of its ancient independence, by reviving in the capital the long-lost fashions of a court, a line of conduct well calculated to procure the affection and esteem of all Scotsmen at the period. The nobility, who had long been depressed under the administration of Lauderdale, experienced a very sensible change in the attention with which they were treated by his successor, and his conciliating behaviour on this occasion is supposed to have laid the foundation of that devotion to his family which promoted the expeditions of his two descendants in 1715 and 1745. His duchess, Mary d'Este of Modena, and his daughter the princess, afterwards Queen Anne, contributed their exertions in the cause. They made parties, balls, and masquerades at the palace, and in a species of dramatic entertainment which they got up, they condescended so far as to act particular characters, and direct the performance. A theatre was subsequently fitted up in the Tennis Court at the Watergate, where there were regular performers from London. They are also supposed to have achieved an infinite degree of favour by treating the ladies of fashion in Edinburgh with tea, at that time a rare and costly entertainment, known only to the highest English nobility, and calculated, no doubt, to strike the fashionable society of the Canongate with the utmost delight and admiration, having never before been heard of in Scotland.

It may easily be imagined, that the result of all this would be highly favourable to Edinburgh. It is said, that old people, about the middle of the last century, used to talk with delight of the magnificence and brilliancy of the court which James assembled, and of the general tone of happiness and satisfaction which pervaded the town on the occasion. The prosperity of the city at this period is testified by numerous circumstances, among which may be specified the large presents which the magistrates at various times conferred upon their royal guest, amounting to no less a sum than eleven thousand pounds. We might also mention the exemplary pattern of loyalty and submission to the existing powers, which the citizens exhibited, at a time when the rest of Scotland resounded with remonstrances against tyranny and persecution. But the most unequivocal proof of their wealth and spirit, is found in a project formed at this time for extending the city over the fields to the north, and connecting them with the old town by means of a bridge; precisely the same notion, which, after being several times re-agitated, was finally carried into effect about eighty years later. James gave the citizens a grant in the following terms, for the encouragement of such an undertaking: " That when they should have occasion to enlarge their city, by purchasing ground without the town, or to build bridges or arches for accomplishing the same, not only are the proprietors of such lands obliged to part with the same on reasonable terms, but, when in possession thereof, they are to be erected into a regality in favour of the citizens," &c. Also "the power to oblige the proprietors of houses to lay before their respective tenements, large fiat stones, for the conveniency of walking." We can here only remark, that the Duke of York seems to have seriously contemplated the good of the city, and that, had his family continued on the throne, it is more than probable the improvements of Edinburgh would have commenced eighty years earlier than they afterwards did, depressed as Scotland and the capital were, by the neglect of succeeding monarchs. Unfortunately the advantages which Edinburgh possessed under this system of things, were destined to be of short duration. The royal guest departed, with all his family and retinue, in May 1682. In six years more, he was lost both to Edinburgh and Britain; and " a stranger filled the Stuarts' throne," under whose dynasty Scotland pined long in undeserved reprobation.* Nothing, perhaps, could so well present an idea of the love of show and luxury which was introduced by James into Edinburgh, than the circumstance of the magistrates having set up a regular state carriage in the year 1684. Finding, it seems, that the expense incurred by their frequent driving about, amounted to more than what would support a regular establishment of a coach and horses, they ordered two coaches from London for their especial use, with four horses. As, even in the present times," the lord provost and bailies of Edinburgh are not indulged with a special state carriage, we may understand the length to which the pageantries of the latter part of the seventeenth century were carried.

In January 1685, the town-council ordered an equestrian statue of Charles II. to be erected in the Parliament Close, notwithstanding the odium which was generally attached to the cabinet measures of that flagitious prince, and immediately afterwards, while the king was within a few days of his death, out of an excess of loyalty, they made an offer to supply him with the cess of seven months. On the demise of Charles, such marks of attention were not forgot by his successor, who returned an answer, thanking them for their hearty zeal in the cause of royalty, on the receipt of which, says Maitland, the magistrates were so transported with joy, that "they ordered an ornamented ebony box to be made, to preserve the document from decay."

The Death of Charles II

Charles II. died on the 7th of February 1685, the news whereof reached Edinburgh on the 10th of the same month, and excited at once regret for the loss of so kind a master, and gladness for the accession of James, the declared friend of the town. A stage was erected at the Cross, on which the chancellor, treasurer, and the whole officers of state, with the nobility, and privy council, the Lords of Session, and the magistrates attended the Lyon King-at-arms, in his proclamation of James, and the whole of them swore fealty and allegiance to him as king. According to Fountainhall, the business was closed by a sermon from Mr. John Robert, who took occasion to bid the audience dry up their tears, when they considered that they had got so brave and excellent a successor! As a tangible symptom of the sycophancy of the town-council to men in power, whosoever they were, we perceive that immediately after the proclamation, they presented Viscount Melfort, one of the principal secretaries of state, with a jewel of the value of £500 Sterling, " as an evidence of their grateful acknowledgments for the many eminent services he had done the city;" and three days afterwards, for delivering the town's address to the king, they gave him the sum of £300 Sterling.

The conduct of James for about seven months after his accession to the throne was not such as to give any uneasiness to the protestants of Scotland, and the system of prosecution for non-conformity had already been modified or stopped. The first public transaction which occurred in the metropolis worthy of notice, after the proclamation of the king, was the execution of the Earl of Argyle, for his concern in the insurrection of the Duke of Monmouth. He was brought into Edinburgh on the 20th of June, and underwent a parade through the streets to the castle, with his hands bound, his head bare, and with the hangman walking before him, in much the same ignominious manner as had been practised on the Marquis of Montrose. It throws additional light on the obscure story of Argyle's conduct, to state, that he was indebted to Heriot's Hospital £58,403, 10s. Scots, which the corporation of Edinburgh was obliged to pay to that establishment.* [*The body of Argyle, after sentence had been executed upon it, was deposited in the chapel of the Hammermen, near the head of the Cowgate, from which it was afterwards transported to the family burial-place, at Kilmun, Argyleshire. ]

The king's partiality to papists became apparent in the month of October, when he ordered the test to be dispensed with, although such rebef could only be granted by parliament, and, in the opening of 16S6, his measures became too flagrant to be longer passed over in silence. The privy council issued orders to every printer and bookseller in Edinburgh, forbidding the printing or selling of any books reflecting on the Romish faith. These respectable tradesmen were not all, however, willing to comply with such arbitrary enactments, and an anecdote is told of the independence of spirit of James Glen, a bookseller in the city, on the occasion. When waited upon by the officer of the privy council, he informed him that he had one book in his shop which condemned popery very much, and yet he would sell it in spite of the mandate he had received. Being asked what book that was, he replied it was the Bible, which was the worst enemy that the church of Rome had ever seen. Glen deserves praise, both for his wit and his intrepidity, for he must certainly be called a brave man who could dare to joke with the privy council of that day, or any of its functionaries.

The public attendance upon mass, by the chief officers of state, about this time, excited a tumult in Edinburgh. A rabble of apprentices, and others, insulted the chancellor's lady, and other persons of distinction, when returning from the chapel, an affront which was resented with great severity. A journeyman baker being ordered by the privy council to be whipped through the Canongate for being concerned in the riot, the mob rose, rescued him from punishment, beat the executioner, and continued all night in an uproar. The king's foot-guards, and soldiers from the castle, were brought to assist the town-guard, in quelling this disturbance. They fired among the mob, and killed two men and a woman. Next day, several were scourged; but the privy council, for the first time, becoming afraid of popular violence, appointed a double file of musqueteers and pikemen, to prevent the sufferers from being rescued. A drummer was likewise condemned and shot, for having said he could find in his heart to run his sword through some papists, and, according to Arnot, from whom we quote, what was fully more abominable, a fencing master was hanged at the Cross for having simply drunken the toast of confusion to the papists, and approved of the late tumults.

While the inhabitants at large, and the country in general, were discontented with these measures, the magistracy of the city continued true to their interests, and assured the ktag of " their hearty devotion to his service, being ready, with their lives and fortunes, to stand by his sacred person, upon all occasions, and praying the continuance of his princely goodness and care towards this his city," — adulation which was remunerated by the restoration of the impost on ale, which, although levied from the inhabitants, had been for some time seized by the treasury. Renewed restrictions were laid on the sale of books reflecting on popery, while those in its favour were published with impunity. Nay, so great was the partiality in behalf of this religion, that a landlady having distrained the printing materials of one Watson, a papist printer, for his rent, the articles were violently rescued from justice, and carried to the sanctuary of Holyroodhouse, where he was protected, and so far encouraged as to be made the king's printer, a situation which, it appears, descended to his son, James Watson, who flourished in Edinburgh in the reign of Anne.

We do not here require to enter minutely into the historical events of this unhappy period. Attachment to the government at length became narrowed within the circle of its own instruments, and the few who were inclined to surrender every right to escape from anarchy and confusion. To political causes of disgust at length were added religious; and men who might have seen one secular privdege taken away after another, without rebelling, became furious when they perceived an attempt to bring upon them the follies of the Catholic religion. By the simple records of Fountainhall, some minor particulars are learned, illustrative of the doings in the metropolis. On the 23d November 1686, says he, "the king's yacht arrived from London, at Leith, with the altar, vestments, images, priests, and their apurtenants, for the popish chapel in the abbey of Holyrood. On St. Andrew's day, the chapel was consecrated, by holy water, and a sermon by Wederington. On the 8th of Febrary, 1688, Ogstoun, the bookseller, was threatened, for selling Archbishop Usher's sermons against the papists, and the History of the French Persecutions; and all the copies were taken from him; though popish books were printed and sold. On the 22d of March, the rules of the Popish college, in the Abbey of Holyrood, were published, inviting children to be educated gratis."

The time at length arrived, when all this was to have an end. No sooner was it known that William, Prince of Orange, had landed, and that the regular troops were withdrawn to reinforce the English army, than the Presbyterians and other friends to the Revolution, flocked to Edinburgh, which, for some time, became a scene of the wildest uproars. The Earl of Perth, chancellor, fled from the city, and the government fell entirely into the hands of the Revolutionists. A mob rose, drums were beat through the streets, the inhabitants assembled in great multitudes, and proceeded to demolish the Abbey of Holyroodhouse, but were opposed by a military party of about a hundred men, who adhered to the interests of James.

The mob pushing forward, were fired upon by this party; about a dozen were killed, and thrice as many wounded, upon which they fled for the present; but quickly returned with a warrant from some lords of the privy council, and headed by the magistrates, town-guard, trainedband, and heralds. Wallace, the captain of the besieged party, was now called on to surrender, and, on his refusal, another skirmish took place, in which his men were defeated, some being killed and the rest made prisoners. There was nothing to resist their fury. The abbey church, and private chapel were robbed and despoiled of their ornaments, the college of the Jesuits, almost pulled down, and the houses of the Roman Catholics plundered. The Chancellor's cellars next became a notable prey to the mob; and wine, conspiring with zeal, inflamed their fury.

Every thing popish in the town was demolished, with a fierceness of hatred much greater than what had been excited at the Reformation of 1560. The religious houses, situated in obscure wynds and closes, which had grown up in the seventeenth century by the countenance of a powerful minority of Roman Catholics, with the private dwellings of persons of that communion, were entered and sacked.

The most instructive particular in the history of these events was the baseness of the privy council and magistracy in suddenly veering to the opinions which, at the expense of tbeir honour, were the most profitable. Notwithstanding the pitiful submission of the town-council to James, and their abject professions of attachment to his person, above noticed, they were the very first in "offering their services to the Prince of Orange; in complaining of the hellish attempts of Romish incendiaries, and of the just grievances to all men, relating to conscience, liberty and property." The only men who remained faithful to their oaths were the bishops and clergy of the established chmch, who, taking the part of James, and being at any rate odious to the people, who were chiefly inclined to a pure Presbyterian form of church government, were the principal sufferers by the new order of things.

On the 14th of March, 1689, a convention of Estates was held at Edinburgh, and was the most important assemblage of the kind which had ever sat in the town. It declared that James had forfeited the crown, which it offered to William and Mary, and preferred the memorable Claim of Rights, or list of grievances to be redressed. It also advised a new election of the magistrates and town council of Edinburgh, to be made in St. Giles' church, by poll of the burgesses, who were liable for public burdens, and for watching and warding; honorary burgesses being excluded, for the very good reason that the sycophantic magistracies of the two past reigns had conferred this honour upon all the worst tools of government. Several ministers were also deprived of their churches, because they declined to pray for the newly appointed sovereigns. The convention was converted into a regular parliament, prelacy was abolished, and the Presbyterian form of church government was established in its place.

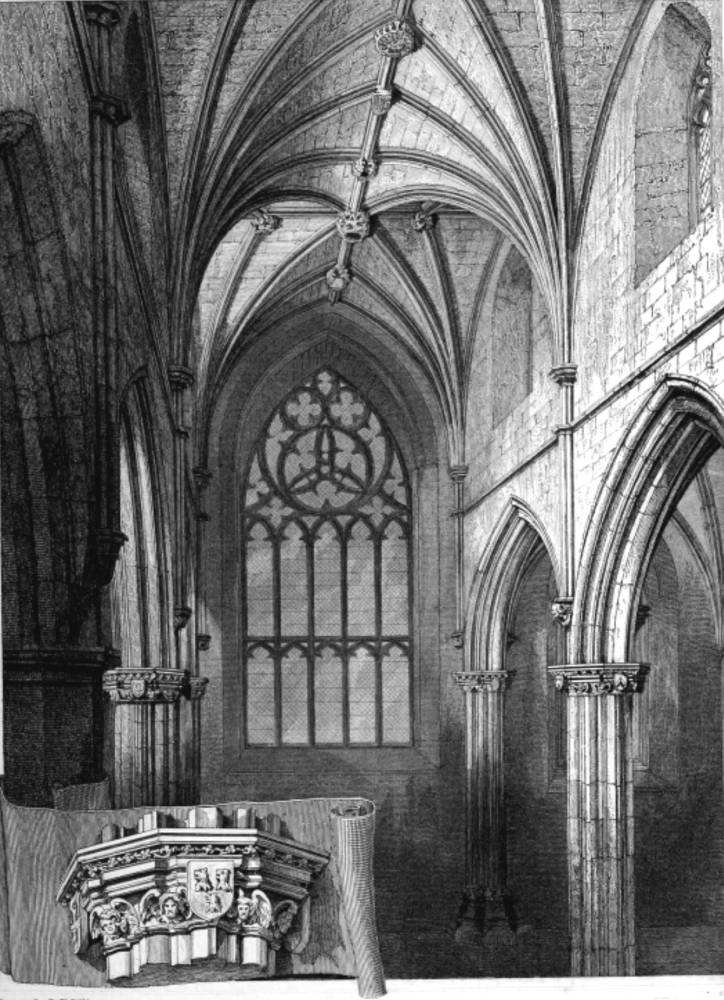

Left: St. Giles’s Cathedral, Edinburgh: The Choir, Looking East. Right: The Tower and Lantern. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In carrying these remarkable measures, which till the present day regulate some of the institutions of Scotland, the convention had a difficult and dangerous task. The castle of Edinburgh was still in the possession of the friends of James, under the Duke of Gordon, its governor, and had it not been out of tender regard to the lives and property of the citizens, this nobleman could, with perfect ease, have demolished not only the Parliament House, where the convention was seated, but every dwelling in the metropolis. To avert such dangers the convention drew together all the available friends of freedom. Among these Were six thousand men from the west of Scotland, chiefly Cameronians, to whom the protection of the new settlement was a pure labour of love, and who, therefore, when the danger was past, refused any gratification for their timely aid, saying, that they came only to serve and save their country.

At this period Edinburgh must have presented a rare and curious spectacle. While crowded with the forces of the convention, some of whom appeared openly on the street in military array, while others were immured in garrets and cellars, the streets and houses were likewise paraded and filled by numbers of violent royalists, and a very little would have been required to precipitate a sanguinary conflict of parties. The chief open supporters of James in the town were Lord Balcarras and Colonel John Graham, of Claverhouse, recently created Viscount Dundee. This last nobleman, who seemed to be the very evil genius of the revolutionists, was attended by a small armed body of fifty horse, ready for any adventure which would be of service to the fallen monarch. At length, however, seeing the enemy to be too powerful, he left the metropolis with his troopers, in order to raise the standard of King James in a scene more congenial to it, the highlands of Perthshire. In passing the castle of Edinburgh, he clambered up the rock on its western and least precipitous side, and at a small postern (now built up) held a conference with his friend the Duke of Gordon, when measures were concerted for their common interest. The departure of this daring individual was not unnoticed by the magistrates or the troops of the convention; but, intimidated by the recklessness of his character, or some other cause, they did not offer to molest him in his march. Intelligence being soon communicated at the Parliament House that he had been seen conferring with the Duke, an alarm got up that he was counselling that nobleman to break up the assemblage by a bombardment; on which the Duke of Hamilton, who acted as president, with great magnanimity locked the door, and declared that no man should go forth till the royalist party should have discovered their intentions, so that recourse might be had upon the persons of their friends in the convention. At the same time drums were beat through the streets to gather the adherents of the revolution, and the city had all the appearance of a city preparing to resist a sudden and unexpected attack. No cannonade taking place, the royalist minority in the convention were suffered to leave the hall; but such was the fright they had received, that they never could venture to return. The convention was then left at liberty to give a cordial and unanimous support to that settlement of the crown and order of succession in the protestant branches of the royal family, which was at the same time perfected by a similar assemblage in England, and is distinguished in British history as the Revolution. The efforts of the Scottish Jacobites, as they were called, ended in the death of Dundee at Killicrankie, July 17, 1689, and the surrender of Edinburgh castle by the Duke of Gordon, June 13, 1690.

Throughout the reign of King William, there was but one parliament in Scotland, with eight sessions, all of which were held in Edinburgh. Except at the commencement of the revolutionary period, this parliament did nothing very remarkable to further civil and religious liberty. Notwithstanding that a law had been passed abolishing the use of judicial torture, the parliament, to its disgrace, countenanced and actually gave orders regarding such practices. Yet, now for the first time, do we find any thing like free debate or eloquent speaking in the Scottish house of parliament In 1689, when the town was stained by the assassination of the Lord President, Lockhart, by Chiesly of Dairy, a gentleman who had considered himself injured by a deliverance of the court, of which the president was chief judge, the parliament gave power to the magistrates to put the accused to the torture, though such does not seem to have been required. The new-modelled government entertained such a jealousy of the college of justice, as to disarm all its members, leaving them only their wearing swords, and the common jail was filled with suspected persons. The Lords Balcarras and Kilsyth, and several gentlemen were confined there, in separate dungeons, like the meanest malefactors. The Earl of Perth, a flagitious instrument of James II. was also seized when attempting to make his way out of the kingdom, and confined without trial, for several years, in a provincial jail. Such things history finds it difficult to pardon, even in a government acting with good intentions for the benefit of the people. All this, moreover, was in despite of bribes taken by Lord Melville, the secretary, to procure the release of the unfortunate prisoners. It further appears by the Criminal Register of Edinburgh, that torture was repeatedly applied to these unhappy friends of arbitrary power, in order to extort evidence, and that to an extent little short of what had been perpetrated before the privy council in the reign of Charles II. Other instances of the arbitrary conduct of the functionaries of the new government are obtained a few years later, when in 1700, the whole of the printers in Edinburgh were summoned before the privy council, and two persons imprisoned, for the publication of some pamphlets reflecting on the proceedings of the government. The crown enacted a still higher stretch of authority; for an engraving being executed, wherein various figures, pictures, and names, were represented, several persons were apprehended; and the author, and one who assisted, were actually tried for high treason before the court of justiciary. Throughout this reign we hear of no hilarity in Edinburgh. " There were frequent fasts, and some thanksgivings ,-" but, the gloominess of the citizens was never, it appears, tempered by such little incitements to mirth, as are apt to disperse melancholy. The birth-days of the king and queen, were, indeed, kept, though only to the extent of drinking their healths at the Cross, and the firing of cannons, there being no concerts, balls, or plays. The magistrates resumed their interference in domestic arrangements as a matter of conscience, and passed a law, quite in accordance with the ideas of liberty entertained by the puritans of the time, to the effect that no vintners or keepers of public houses should presume to employ any female servant in drawing or serving any ale or liquors in any of their houses, under a penalty of three pounds Scots; also no woman was allowed to keep any of the said places for the sale of liquors, or hire herself to any person to be employed in that service, under a double penalty. Erom such regulations as these we may comprehend that the public morals of the metropolis were then in a low condition. A more useful statute was enacted in 1698 by the Scots parliament, regulating the height of houses in Edinburgh, in order to lessen the danger of the inhabitants in cases of fire. It was ordained that in future no house should be elevated to a greater height than five storeys, and that the walls on the ground storey should not be less than three feet in thickness. Such precautions were not unnecessary. A dreadful conflagration, long remembered in Edinburgh, broke out on the south side of the Parliament Close, on Saturday night, the 3d of February 1700, which destroyed an extensive pile of building, on the south and east sides, exclusive of the Treasury Room and the old Royal Exchange.

However popular William had been on his accession to the throne, the Scotch in general, and the Edinburghers in particular, had reason to be opposed to his administration. The massacre of Glenco excited no less the national discontent, than the failure of the Darien expedition roused the inhabitants of the metropolis. In prosecution of this trading speculation, six ships of considerable burden, laden with various commodities, sailed from the Firth of Forth, 1696, in the presence of a vast crowd of persons of all conditions belonging to the city. The news of the settlement being formed on the isthmus of Darien, arrived in Edinburgh on the 25th of March 1699, and was celebrated with the most extravagant rejoicings and by thanksgiving sermons. In the course of the following year, therefore, when intelligence was received of the failure of the settlement, through the influence of William, the town was thrown into a corresponding degree of rage. The mobs committed different serious outrages in their transport of fury; they opened the prison doors to those printers who had been confined by the government, and the commissioner and officers of state found it prudent to retire for a few days, lest they should have fallen sacrifices to popular indignation.

On the accession of Queen Anne, it was not found expedient to call a new parliament, and, thoufh the meeting of the old one was clearly illegal, it sat in 1702, under the Duke of Queensberry, as the queen's commissioner. At this period occurred in Edinburgh the tumult so often noticed by historians, relative to the seizure of the vessel of Captain Green. A ship belonging to the Scottish African Company had been seized in the Thames, for which no compensation being given, the government at home gave the owners liberty to seize, by way of reprisal, a vessel belonging to the English East India Company, which put into the Firth of Forth, and of which a Captain Green was commander. "The unguarded speeches of the crew, in their cups, or their quarrels, made them be suspected, accused, and, after a full and legal trial, convicted of perjury, aggravated by murder, and that committed upon the master and crew of a Scots vessel, in the East Indies. Still, however, the evidence upon which they were condemned, was by many thought slight, and intercession for royal mercy were used in their behalf. But the populace were enraged that the blood of Scotsmen should be spilt unrevenged. On the day appointed for the execution, a vast mob surrounded the prison and Parliament House, where the privy council, assisted by the magistrates of Edinburgh, then sat deliberating whether the sentence should be executed. The furious intentions of the populace were well known, and the magistrates assured them that three of the convicts were ordered for execution. The Lord Chancellor then passed from the privy council in his coach, when some one called aloud, "that the magistrates had but cheated them and reprieved the criminals." Their fury instantly kindled into action. The chancellor's coach was stopped at the Tron Church, the glasses were broken, and himself dragged out of it. Happily some friends of his lordship rescued him. But it became absolutely necessaiy to appease the enraged multitude by the blood of the criminals."

We learn from Maitland, who quotes from the council register, that in the month of March 1704, the inhabitants of the town were regaled with an edifying spectacle at the Cross. In obedience to an act of the privy council, there was carried thither and burnt, a great quantity of popish trinkets, consisting of sacerdotal habiliments, communion-table linen, portraitures, chalices, crucifixes, whipping cords, strings of beads, consecrated stones, relics, remissions, and indulgences, among which was the following:

The Archbishop of Mechlin has granted Indulgence of fortie days to those who shall bow the knee before this Image once a-day; considering devotly the infinite Charity of Jesus Christ who hes suffered for us the bitter Death of the Cross: And if any one will perform this Devotion oftner, he shall so oft have a new Indulgence for five Days more.

It is discovered, by the records of the Kirk Sessions of Edinburgh, that about this time, the constituted authorities did not confine their zeal in the cause of protestanism to simply burning the trumpery of the popish chapels; the most unjustifiable severities continued to be practised on Roman Catholics, who were ordered to be searched for, and seized wheresoever they could be found. Some very curious laws seem also to have been passed by these petty tribunals, prohibiting gaming with cards and dice, and giving power to persons to seize in private houses or taverns all who indulged in these amusements.

Besides some laws regarding domestic economy, several enactments were passed by the Scots parliament of 1704, which, from their design, and the temper in which they were conceived, showed to both the English and Scottish nations that they could no longer go on with a separate administration, yet under one sovereign, The time arrived when either a complete separation or a close union was necessary, and such circumstances were not unnoticed by the queen. On the 11th of January 1705, a bill was brought into the English parliament, enabling the Queen to appoint commissioners, to treat of a union with Scotland, and the Scots parliament, on the 28th of June, followed that example of conciliation. But the junction of the two kingdoms was speedily found to be a matter almost beyond human skill to effect.

The national antipathies which had subsisted between Scotland and England from the earliest periods of their histories, heightened by the pride, jealousy, and mutual injuries of both nations, and which had hitherto baffled every attempt towards their union, far from being allayed, were, by recent misunderstandings and offences, exasperated into keener animosity. The opposite views of different parties as to the succession to the crown upon the demise of Queen Anne, also served to lessen the chance of a proper union being instituted. If the passions and interests of the Scots were deeply engaged in an object of so much importance, those of the city of Edinburgh were so in a particular degree. Its citizens saw, in the event of a union, the withdrawal of the national councils, parliament, and every semblance of royalty, which sustained their wealth, and gave their town the character of a capital. They were, therefore, deeply concerned in the passing of the act of union, and when the measure came before parliament in October 1706, they broke out into a species of rebellion against the constituted authorities. The Articles had been industriously concealed from their knowledge; but on their being printed, universal clamour ensued. The parliament being then sitting the outer parliament house and the square adjoining were crowded with an infinite number of people, who, with hootings and execrations, insulted every partizan of the union, especially the Duke of Queensberry, to whom was committed the delicate task of carrying through the act, while those who headed the opposition, were followed with the loudest acclamations.

Nor did the populace confine themselves to such empty marks of indignation. On the 23d of October, the mob attacked the house of Sir Patrick Johnston, a strenuous promoter of the union, their late lord provost, and one of their representatives in parliament. By a narrow escape, he saved himself from falling a victim to popular fury. The mob increasing, rambled through the streets, threatening destruction to the promoters of the measure. By nine at night they were absolute masters of the city; and a report prevailed, that they were going to shut up the ports. To prevent this, the commissioner ordered a party of soldiers to take possession of the Netherbow, and afterwards, with consent of the provost, sent a battalion of foot guards, who posted themselves in the Parliament Square, and the different lanes and avenues of the city, by which means the mob was quelled. The panic which seized the commissioner, and others concerned in the treaty of union, was not, however, allayed. For their own protection, and the support of their measures, the whole army was brought into the neighbourhood of Edinburgh. Three regiments of foot did constant duty in the city, a battalion of guards protected the abbey, and the horse guards attended the commissioner. None but members were allowed to enter the Parliament Square while the house was sitting; and his Grace the Commissioner walked from the Parliament House, amidst a double file of musqueteers, to his coach, which waited at the Cross; and he was driven from thence at full gallop to his lodgings, hooted, cursed, and pelted by the rabble.

In the midst of those disturbances, and under the protection of a military force stationed in the capital, the parliament, on the 16th of January, 1707, ratified the Articles of Union, which being subscribed by the commissioners, the measure was completed. As illustrative of the troubled state of the metropolis, while the last blow was in the course of being given to the ancient independence of the kingdom of Scotland, it is stated by tradition, that some of the subscriptions of the Commissioners were appended in the arbour or summerhouse in the garden behind the Earl of Murray's house in the Canongate, but the mobs getting knowledge of what was going on in this secret spot, the commissioners were interrupted in their proceedings, and had to settle upon meeting in a more retired place, when opportunity offered. An obscure cellar in the High Street was fixed upon, and hired in the most secret manner. The noblemen whose signatures had not been procured, then met under cloud of night, and put their names to the detested contract, after which they all immediately decamped for London, before the people were stirring in the morning, when they might have been discovered and prevented.* [*The place in which the deed was thus finally accomplished, is pointed out as that laigh shop, opposite to Hunter's Square, No. 177. High Street, and now occupied as a tavern and coach office. It was in remote times usually called the Union Cellar, but has entirely lost that designation in latter years.]

The anticipations of the city of Edinburgh were at first fully verified in the desertion of the capital by the officers of state, and noblemen and gentlemen connected with the parliament. All those who had been instrumental in carrying through the Union fled to the favourable climate of the English court, where honour and preferment awaited them; and, with the exception of those gentlemen engaged in legal pursuits, and a small and poor minority who had voted on the popular side, the city was suddenly deprived of all its upper classes. On witnessing this desertion of its best inhabitants, a sound of sorrow and indignation went through the city, similar, perhaps, to the waitings which followed the disaster of Flodden, when in the words of the ballad,

The flowers of the Forest were a' wede away.

Besides the money which had been circulated in the town by the constant residence of those connected with the parliament, great sums were spent among the tradesmen of the city on the sumptuous garments of the different functionaries, and the splendid furniture of their attendants and horses. The pageant called the Riding of the Parliament, had been for centuries, one of the very finest things of the kind, and being considered a matter of high concernment in the metropolis, its loss was felt as a robbery of the city of its head gala. So much has been heard of this gorgeous procession, and so little is now actually known of it, that we feel disposed to insert a short description of the Riding which occurred on the 6th of May, 1703 —

The High Street and Canongate were cleared of all coaches and carriages, and a lane formed by the thoroughfare was inrailed on both sides, within which no spectators were permitted to enter. Without the rails, the streets were lined with the horse-guards from the palace of Holyrood, westward; after them, with the horse-grenadiers; next with the footguards, who covered the street up to the Netherbow; and then to the Parliament Square by the Lord High Constable's guard; and from the Parliament Square to the bar, by trained-bands, or city militia, and the Earl Marischal's guards; the Lord High Constable was placed in state in an elbow chair at the door of the House. While these troops and officials were taking their appropriate places, the officers of state and members of parliament with their attendants, assembled in the court-yard in front of Holyrood-house. All being arranged, the rolls of parliament were called by the Lord Register, Lord Lyon, and Heralds, from the windows and gates of the palace, after which the procession moved to the Parliament House in the following order:

Such was ordinarily the arrangement of that celebrated pageant, a riding of the Scots Parliament, the king himself occupying the place of the Commissioner, when he attended. In times of Episcopacy, a ceremony of a striking nature is said to have prevailed on the occasion. As the gay procession moved up the High Street, while every window was crowded by delighted spectators, the Bishop of Edinburgh appeared on a brazen balcony, which projected from his house on the north side of the street, and, leaning forward with outstretched arms, blessed the parliament, in passing. At the same period the spiritual lords had a place in the order of the procession, and, with their sacerdotal robes, must have added considerably to the dignity of the spectacle.

Being defrauded of a pageant of so much grandeur, and all pertaining to it, the city of Edinburgh long languished in profitless repose. From the Union (which took effect on the 1st of May, 1707,) up till the middle of the century, the existence of the city seems to have been nearly a total blank. No improvements of any sort marked this period. On the contrary, an air of gloom and depression pervaded the city, such as distinguished its history at no former period. A tinge was communicated even to the manners of society, which were remarkable for stiff reserve, precise moral carriage, and a species of decorum amounting almost to moroseness — sure indications, it is to be supposed, of a time of adversity and humiliation. The meanness of the appearance of the city attracted no visitors; the narrowness and inconvenience of its accommodation, and the total want of public amusements, gave it few charms for people of condition as a place of residence; and the circumstances of the country were such as deprived it entirely of political and commercial importance. In short, this may be called, no less appropriately than emphatically, the dark age of Edinbivrgh.

In the course of this dismal period, the magistracy of the town, in the spirit of the times, enacted laws as ludicrous as they were absurd. Not satisfied with the different corporations having exclusive privileges to exercise separate trades, they created monopolies of almost every occupation that can be imagined. Arnot tells us that one person got an exclusive privilege of printing newspapers three days in the week; another of printing burial-letters; a third of dispersing burial-letters; a fourth of japanning; a fifth of keeping chaises to ply between Edinburgh and Leith; a sixth of keeping stagecoaches going between these two towns; a seventh of hawking ballads and last speeches, &c. Printers were prohibited from printing unlicensed pamphlets, under the penalty of losing the freedom of the burgh, and being otherwise fined and punished at the will of the magistrates!

And they held so watchful an eye over the education of youth, that none durst teach dancing, in public or private, with, in the city or suburbs, without licence obtained from the council. A most rigorous attendance on public worship was enforced. Certain functionaries, like the Alguazils of the Inquisition, and called seizers, patrolled the streets, and apprehended those found walking in them during the time of Sermon. They prohibited all persons from being in taverns after ten at night, under severe penalties to individuals so caught, and a fine of tenpence each to the keeper of the house.

Absurd and extravagant punishments for incontinence continued to be inflicted, the consequence of which was that child-murder was exceedingly frequent. "Women in the lower ranks of life were in the most deplorable condition imaginable. The young, if they lost their chastity, were harassed and terrified into crimes which brought them to the gallows; and the old, under the vile imputation of witchcraft, were tormented by the rabble, till, by the confession of an imaginary crime, an end was put to their sufferings." The very amusements indulged in by the more lively spirits of the age were of a debasing kind; consisting chiefly of cock-fighting and such like pastimes; and it appears, to such an extent was this passion carried, that the magistrates discharged it being practised in the public thoroughfares, on account of the disturbances it created. For many years, the principal business of the town-council was the concoction and presentation of humble addresses to the throne, describing the sinful state of the inhabitants, while, with a zeal fully as officious, the presbytery issued edicts referring to the affairs of private life or the mere recreation of individuals, so preposterous and tyrannical, that we are amazed how they were submitted to by people, possessed, as we are told, of very exalted notions of civil and religious liberty.

Bibliography

Chambers, Robert. The Gazetterr of Scotland. Edinburgh: Blackie and Son, 1838. Internet Archive online version digitized with funding from National Library of Scotland. Web. 30 September 2018.

Last modified 3 October 2018