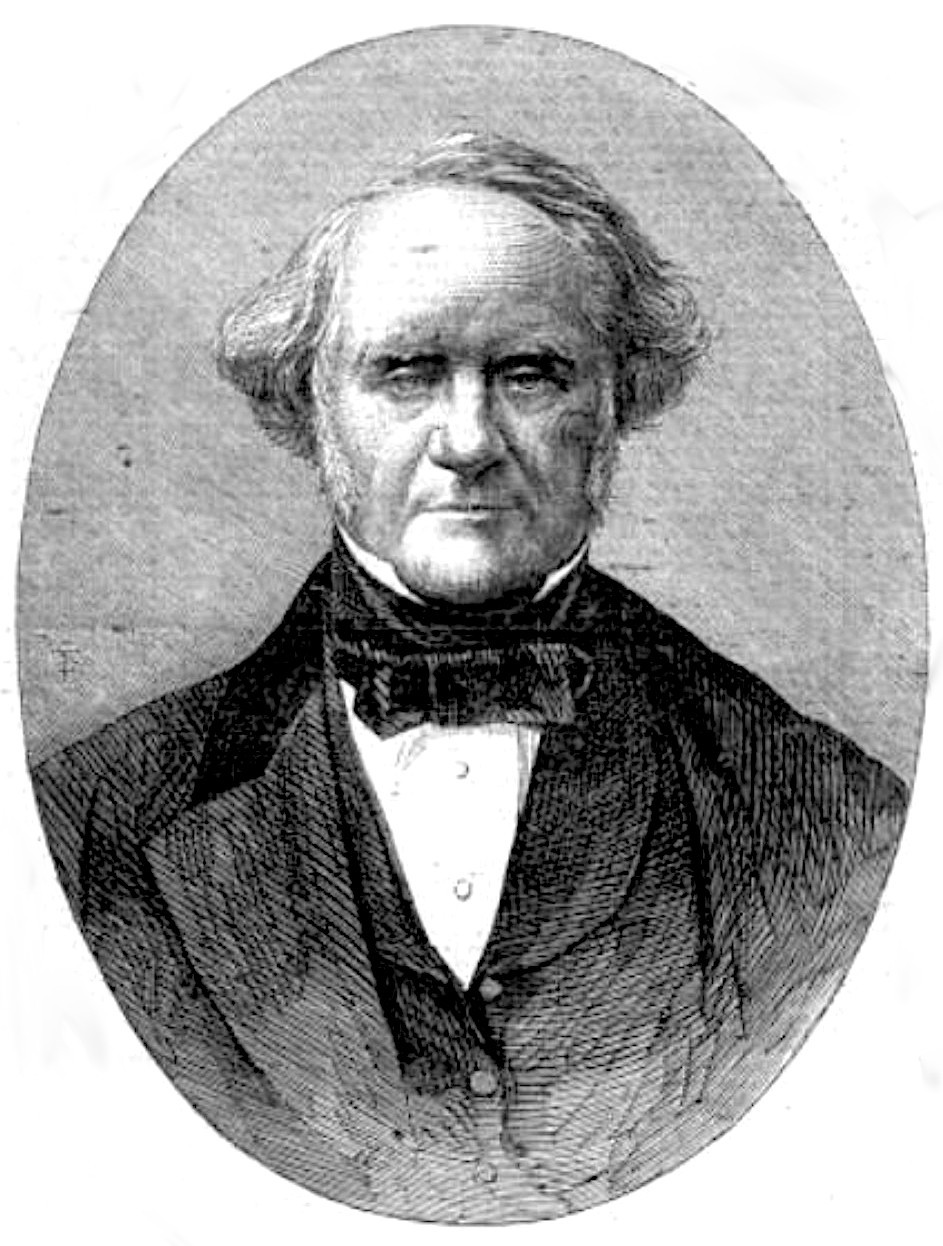

The following account and portrait come from the copy of the Illustrated London News listed in the bibliography below. The article has been transcribed and formatted for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee.

his gentleman, whose munificent act [the donation of a large fund for the amelioration of the conditions of the London poor]is now the theme of common discourse throughout the land, and whose Portrait is given on page 335, is a native of Danvers, Massachusetts, where he was born Feb. 18, 1795. He is the sixth in descent from Francis Peabody, who, at the age of twenty-one, and in the year 1635, went to New England from St. Albans, Herts. He died, in 1698, the father of fourteen children, of whom six were sons. His name is now a common one in Massachusetts. The parents of the subject of this brief memoir were not blessed with any superfluity of means, and the future merchant prince of both worlds gained all the scholastic education he ever acquired at the district common school of his native town. At the early age of eleven he was placed in a grocer’s store in Danvers, where he remained four years. At the age of sixteen the youth was invited to help an elder brother in a dry-goods business in Newburyport, then, as now, one of the principal seaport towns of Massachusetts. His brothr brother was soon "burnt out" in the conflagration still known to local fame as the great fire of Newburyport. In May, 1812, his uncle started a dry-goods business in Georgetown, in the district of Columbia, and called upon his nephew to join him. The management of the business devolved upon the younger relative. But for a time the pressing demands of patriotism made themselves heard above those of business. The war of 1812 had broken out, and George Peabody joined a volunteer company of artillery formed at Georgetown, and found himself on active duty at Fort Warburton. Happily, no engagement took place, and the volunteer soon returned to the more congenial and more profitable pursuits of peace. He remained with his uncle two years. Business was not promising, and he reluctantly withdrew from it.

There was one man. however, who had noticed the remarkable ability and activity of youmg Peabody, and who judged that in him the capitalist would gain a desirable coadjutor. This man was Mr. Elisha Riggs. Mr. Riggs proposed to find the capital to establish a dry-goods business which young Peabody was to manage. The discovery that the latter was only nineteen years of age did not make Mr. Riggs waver. And now Mr. Peabody entered the channel which led directly to his great success in life. In 1815 the house was removed to Baltimore; and in 1822 the extension of its operations justified the establishment of branches in Philadelphia and New York. In 1829 Mr. Elisha Riggs retired, and Mr. Peabody became senior partner.

About this time, Mr Peabody began to visit Europe. On more than one occasion he was charged with important negotiations for the state of Maryland. For his gratuitous services to the State the General Assembly passed a vote of thanks to their generous agent and representative. Early in 1837 he took up his abode in London. He had not been in London long when the financial crash of 1837 occurred, which prostrated American credit in England. Mr Peabody's optimistic views of the elastic resources of his native country, sound though they were, were received with scepticism in the City, but established for him a solid title to the gratitude to the American world of commerce. In 1843 Mr Peabody retired from the firm of Peabody, Riggs, and Co., and established the money-dealing house of George Peabody and Co., of which he is still the efficient and active head. In this business he became a millionaire. His biographer, in Hunt's Merchants’ Magazine, to whom we owe the principal facts in the above sketch, thus enumerates the qualities which have contributed to this result:—'A judgement quick and cautious, and clear and sound; a firm will, energetic and persevering industry; punctuality and fidelity in every engagement; justice and honour controlling every transaction; and courtesy — that true courtesy which springs from genuine kindness — presiding over all the intercourse of life."

Mr Peabody's career has another aspect besides the financial. His position as a merchant has served only as a foil to dispay him in the character of a humanitarian. The Anglo-American merchant, though not professional politican, only perceived that his position would enable him to act as a link between the English and American people. His Fourth of July dinners, where philo-American English and philo-English American gentlemen sat around the same table and made an annual demonstration of international fraternity in the eyes of the two worlds, constitute an event in the history of the relations of the two kindred, but alas! too often alienated nations. These dinners were discontinued only when there was a body of American residents who were ready to take the good work out of Mr Peabody's hands.

Mr Peabody is not encumbered by family ties; he is a bachelor; his collateral relations, some of whom he supported when he was a very young man, have long since ceased to need help from him. Of the copious stream of private benefactions which he dispensed to needy Americans in England we can speak only from general repute, but the monuments of his public beneficence are, or soon will be (we may almost say), scattered over the world. To his native town he has given about 100,000 dols [dollars], to found a library and lecture fund. The Peabody Institute of Danvers is now in active operation. To the citizens of Baltimore — the city where he spent more than twenty years of his business life, and where he gained that standing which was the source of his success in London — he gave, in 1857, the sum of 500,000 dollars to found an institute in that wealthy but heretofore unlettered city, which should embrace a free library, a fund to pay for lectures to which certain classes were to have free admission, an academy of music, a gallery of art, and premises for accommodation of the Maryland Historical Society. The opening of this institution has been retarded by the war in America, which has brought upon Baltimore the inconveniences of a military occupation. His last public benefection, that of £150,000 for the benefit of the poor of London, differing in kind as it does from which he has bestowed upon his native country, surpasses them all in magnitude. It has long been the praiseworthy fashion of American millionaires, after providing amply for their families if they have any, to found with the bulk their wealth some public institution, promotive of the intellectual or physical welfare of their fellow-citizens. Thus, New Orleans has had her M‘Donogh, Philadelphia her Stephen Girard, Boston her John Lowell and Abbott Lawrence, Oswego her Gerritt Smith, New York her John Jacob and William B. Astor and her Peter Cooper, and Baltimore her Peabody. The last has excelled all other American public benefactors, not alone in the extent and variety of his munificence, but especially in this respect — that while they will be remembered by a grateful posterity in one branch only of the English-speaking race, the memory of our Anglo-American Mecaenas will be an inheritance shared equally between Britain and the United States, and will add one to that long list of names in politics and literature which both nations delight to honour, and which serve to nourish a sentiment which moderates the violence and survives the effects of temporary causes of estrangement.

Bibliography

"Mr. George Peabody." The Illustrated London News. 5 April 1862. Vol. 40: 333 and (portrait) 335. Internet Archive. Digitalisation sponsored by the Kahle/Austin Foundation. Web. 14 December 2021.

Created 14 December 2021