Soldiers, as the reader will readily suppose, are among the most clubbable of men; and many a poor officer in India consoles himself for the fatigues and discomforts of station-life by looking forward to the moment when he will once more pass the portals of his beloved Pall Mall or Piccadilly, and revel in the luxuries that await him there. New York Times May 28, 1876

or men who ruled and administered the empire, it was not only the people, but the places of home that they missed. Men in Bombay, Capetown and Mombasa dreamed of the comfortable familiarity of a rich meal, a fine cigar, and a snug seat by the fire of home. But on coming home, sometimes the familiar did not feel familiar enough; the dream of home did not match the reality. This held true in many areas of life from family to work to friendship. However, one nineteenth-century institution addressed the issue head on: the gentlemen’s clubs of London.

On the outskirts of Empire, men formed clubs to remind them of home, and maintain English gentlemanly traditions. Mrinhalini Sinha has done a good job highlighting the important role that clubs served in India (“Britishness, Clubbability”). These institutions helped reproduce the exclusive feel of a London club they missed, also helped to reinforce racial barriers. They helped to incorporate Europeans into new colonial political and social order. Studies like E.M. Collingham’s Imperial Bodies do a great job of explaining how the British saw themselves in the colonies, how it transformed not only their perceptions, but their physical selves. Imperial workers defined themselves not just against the “other” of their Indian subjects, but in reference to an imagined normalcy back home. But what these stories are not able to address are the experiences of the men who return home after prolonged time in the colonies. Thousands of men lived in, maintained and ruled the empire for decades; and then they came back to Britain.

Returning home after living abroad for a number of years, many Imperial travellers were surprised to experience a kind of culture shock. This shock was all the more surprising as holding on to their British identity was often paramount in the imperial setting. Clubland realized the problem of returning men from the empire very early. In the 1820s, when company officials returned to London they tended to group together. Some joined the Alfred club, a social club that happened to have several imperial members, others joined the Travellers, a club open to all gentlemen who had travelled more than 500 miles from London. If one were in her majesty’s forces, the United Service was a possibility as of 1815; but this was a popular club with a long waiting-list. The Army and Navy Club was only formed in 1838. There were a number of “imperial” sounding clubs in the West End: the Calcutta club, the Madras Club, the Bombay Club. And yet these were formal associations, not real clubs. And as contemporary observers noted, these were frequented by merchants and bankers of the middling orders, not the elite society many returning gentlemen craved (Wheeler, Oriental Club, 43). In the ever-expanding world of London clubs, the need for an institution explicitly catering to the men of Empire was paramount.

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, many such men returned to England without a wife or children. There were few opportunities to find an English wife in early nineteenth-century India, and the idea of taking a native wife were increasingly frowned upon (Wheeler, 39). As one club chronicler wrote: “Indian habits, Indian luxuries, and Indian lassitude had grown upon them, and while they, on the one hand, were dubious as to the wisdom of taking back on their return to duty an English wife, on the other hand the majority of English parents were disinclined to allow a young girl to encounter the inconveniences of a long voyage and the peril and dangers of a prolonged residence in a distant land, of which their knowledge was very limited” (Wheeler, 41). Some feared even returning to their ancestral homes in the countryside as their climate and temperature was too harsh. A life in London was understood to be the “healthy” alternative (Wheeler, 39). Two clubs, The Oriental Club (1824) and the East India United Service Club (1849) were creations specifically founded to cater to the hybrid identities of the returning men of the Empire.

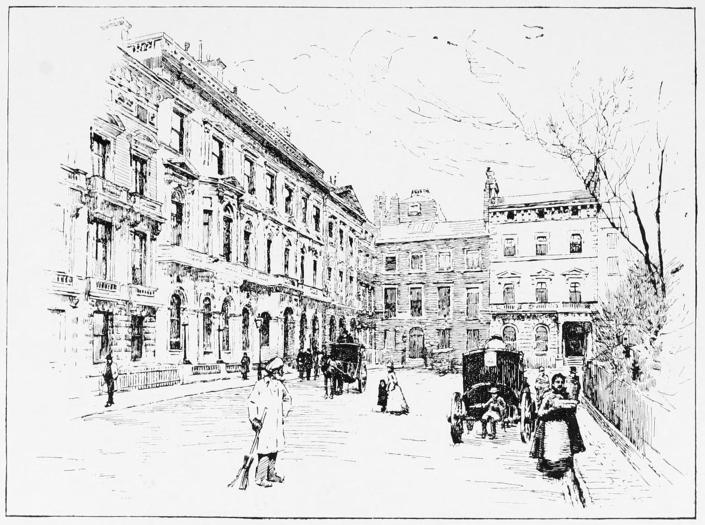

Left to right: (a) East India United Service Club. (b) Oriental Club [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

A single man, away from his country for many years, might need help reacquainting himself with polite society. And a gentlemen’s club was just the kind of institution to cater to the particular challenges of imperial travellers coming home. The Oriental Club explicitly set out three primary goals:

1: To craft connections with English society

2: To meet and reconnect with old friends

3: To keep men abreast of Eastern affairs for those who needed to maintain their connections (LMA/4452/01/03/001)

A notice published in the Asiatic Journal explained the need for such a club: “The British empire in the East is now so extensive, and the persons connected with it so numerous, that the establishment of an institution where they may meet on a footing of social intercourse, seems particularly desirable” (April 1824, 473). In the prospectus for the first meeting of the Oriental Club, the committee explicitly outlined a reading room well stocked with periodicals and newspapers relating to the east; their library was formed around works on oriental subjects (LMA/4452/01/03/001). The club also embraced government delegates coming from the colonies as honorary members during the period of their official stay (LMA/ 4452/01/03/017). The Oriental Club filled quickly, and there was a clear need for a club catering to the various services that administered the Indian government (Timbs, Curiosities of London, 248).

Officers of East India Company, when on furlough or retired, had no regiment where they might renew acquaintance with old friends and brother officers, no club they could resort to (unlike army officers who had the United Service). Members of the Indian Civil Service faced a similar dilemma (Wheeler, 28). The East India United Service Club was formed with explicit ties to its home company to serve these needs. After the dissolution of the company, the East India United Service Club lost its exclusive Indian character, but still offered a home to many returning imperial travellers, and it developed a martial character (The Builder, 153). Both the Oriental and the East India Clubs offered a particular refuge for men who needed a space to transition back to a home that now seemed unfamiliar.

The need and usefulness of these clubs cannot be underestimated. Sometimes membership these London clubs was the only tangible connection men had to their homes while they were away. Many men maintained their memberships to their clubs even if they could not visit them for decades. Paying the annual subscription fee was a concrete connection to home. Many London clubs set up reduced fees and payment schedules for “out of town” members, and those in foreign service. Others made no concessions to their members abroad and men paid full dues to a club they could not attend. And yet, membership was considered enough of a priority for imperial members to pay these annual dues. They realized that many clubs had waiting lists of years, even decades at their peak, and thus the payment was worth holding their place.

Another reason imperial veterans strove for a home of their own in the capitol is they were not always welcome elsewhere. Not all Londoners looked too kindly on these returned Imperial veterans. The aura of the nabob hung heavily over many. The Anglo-Indian was an easy target; somehow, he was no longer entirely English. Some critics wondered if these men might not have brought back a sense of “oriental Luxury” with them (Clubmen of London, 10). That perhaps living among uncivilised people, they had become uncivilised themselves. In particular, returning imperialists struggled with their class position. Accustomed to living in relative luxury in imperial settings, their return home almost invariably entailed “loss of position and consequence and relegation to the unofficial world (Wheeler, 39). These men were understood to be strange relics from a distant world. John Timbs listed the Oriental Club as one of his London curiosities: “it looks like an hospital, in which a smell of curry-powder pervades the ‘wards’⎯wards filled with venerable patients, dressed in nankeen shorts, yellow stockings and gaiters, and facings to match” (Timbs, Curiosities of London, 253). Clubs like the Oriental and the East India could act as both essential lifelines and a safe refuge between imperial and domestic life.

Max Beerhbohm’s semi-fictional tale, “A Club in Ruins,” embodied the reasons why imperial men placed such a priority on their London clubs. The narrator of the story looks on as an old clubhouse is being torn down. He then spots a “bronzed and bearded” stranger looking at remains of his old club. He had been elected ten years previously, but had never been able to enjoy it before being sent to Australia by his father. Beerbohm writes: “The one thing which enabled him to endure those ten years of unpleasant exile was the knowledge that he was a member of a London club. Year by year, it was a keen pleasure to him to send his annual subscription. It kept him in touch with civilisation, in touch with Home” (60-61). The man was put completely at a loss with the destruction of his club, and he felt he had no hope of reconnecting with London society. He decided to return to Australia, because without the club there was no home for him in England.

Related Material

Bibliography

Beerbohm, Max. “A Club in Ruins” Yet Again 3rd ed. London: Chapman and Hall, 1909

“The Clubmen of London: An Account of many famous institutions,” New York Times March 2, 1890, 10.

Collingham, E.M. Imperial Bodies: The Physical Experience of the Raj, c. 1800-1847 Cambridge: Polity 2001.

"The East India Club, St. James's-Square," The Builder march 3, vol. 24, no 1204 1866, 153.

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA/4452/01/03/001; LMA/4452/01/03/017)

Milne-Smith, Amy. London Clubland: A Cultural History of Gender and Class in late-Victorian Britain. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. [Not in original article]

“Miscellaneous,” The Asiatic Journal, April 1824, 473.

Sinha, Mrinhalini. “Britishness, Clubbability, and the Colonial Public Sphere: The Genealogy of an Imperial Institution in Colonial India,” Journal of British Studies 40:4 (2001): 489-521.

Timbs, John. Curiosities of London. London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1868.

Wheeler, Stephen, ed. Annals of the Oriental Club 1824-1858. London: printed for private circulation, 1925.

Last modified 1 October 2013