In 1864, John Lawrence, Viceroy of India from 1864-1869 and previously Chief Commissioner of the Punjab, declared Simla (present-day Shimla) to be the summer capital of India. This was then a small settlement high in the Himalayan foothills and far from the seat of power in Calcutta, but cool, healthy and strategically placed among (as Lawrence himself argued) "all the warlike races of India, all those on whose character and power our hold in India, exclusive of our own countrymen, depends" (qtd. in Kanwar 35). Accordingly, for many years the Government officials and the whole burden of their bureaucracy were borne across plain, river and up steeply winding slopes on an annual migration of some 1,200 miles: the railway link was not completed until 1903, and even then, as now, the last several hours were by slow, uphill narrow-gauge railway through over a hundred tunnels — a massive feat of late Victorian/early Edwardian engineering, and still the longest mountain railway in India.

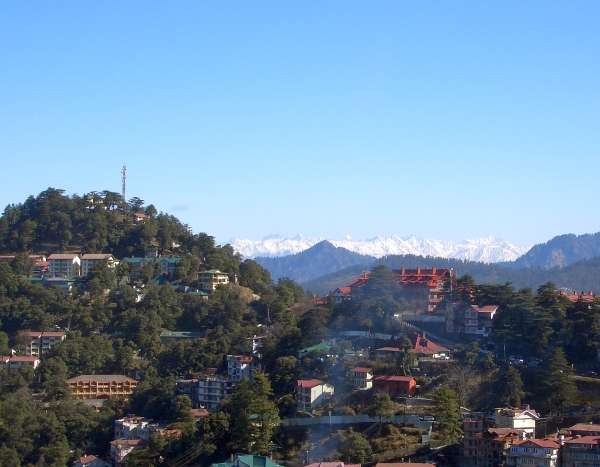

Left: View from Shimla towards the pine-clad valley. Center: View from Shimla towards the snowcapped Himalayan peaks, often hidden by mists. Right: Shimla today. [Click on thumbnails on this page for larger images.]

Summer in India is, of course, very different from an English summer. The season during which strict regulations were in force for local residents in Simla (no begging, for instance) was between March 15 and October 15 inclusive (see the bye-laws reproduced in Kanwar 260). This means that the subcontinent, the "jewel in the crown" of Empire, was actually ruled from Simla for the better part of the year. The British loved the fresh mountain air, the beautiful valleys on one side and the Himalayan views on the other. To them it was indeed the Queen of Hill Stations, beating other summer retreats like Mussoorie, Nanital and Ooty (Udhagamdalam) which also laid claim to that title. Making full use of local labour, they dug in and made themselves at home there, building residences nostalgically modelled on Tudor cottages and baronial manors: houses with names like Holly Lodge and Walsingham. One such house, Rothney Castle, built high on the hill overlooking the main part of Simla, came to be the residence of A. O. Hume, the retired administrator who founded the Indian National Congress in 1885. Below Hume's estate (though, as a theosophist, he would have had little to do with it) is the eye-catching yellow-painted Christ Church, consecrated in 1857, which stands proud at the eastern end of the Ridge. St Michael's Roman Catholic Cathedral, consecrated in 1886, was erected in a less dominant position at the other end of town, just below the Mall. A hospital, post office and telegraph office also sprang up, and shops reminiscent of those in English market towns lined the Mall. By 1888 there was a town hall complex spanning the Ridge and the Mall beneath it, and including the Gaiety Theatre, a ballroom and so on.

Other impressive structures crowned the rugged slopes of the summer capital. The most unusual one speaks of the Victorians' pride in industry. This is the technologically-advanced cast-iron and steel Railway Board Building of 1896-97, supported on the steep hillside by its three basements; it was restored after a fire struck the top floor in 2001, but its sturdy internal features were found to be intact. Another fairly startling reminder of the aspirations and utter self-confidence of the Victorians in India is nearby pinnacled Gorton Castle, built at the very end of the period (1901), and soon to house the Imperial Civil Secretariat. But even this unusual building could not outshine Henry Irwin's grandiose symbol of Empire: the neo-Gothic Viceregal Lodge (1888), which is sited about six kilometres from the main part of the Mall on an eminence called Observatory Hill. This is visible from far down the valley, and must have been a welcome sight on the approach from Calcutta. Inside, this too had state-of-the-art technology. It had its own steam generator, and it was here that Lady Dufferin, the first Vicereine in residence, first operated an electric light switch. The original light panel is still there. Since all these buildings, large and small, were made from local materials by local craftsmen, they also embrace elements of Indian design as well as making concessions to their environment. Examples are the verandas around the bungalows, the Rajasthani-style balconies which adorn Gorton Castle, and the intricate Kashmiri designs in the walnut ceiling of a lounge in the Viceregal Lodge.

Life in Simla was clearly not simply a matter of pen-pushing and paper-shuffling. "Of all the hill stations, Simla was by far the most glamorous," writes Charles Allen, going on to quote an old India-hand's memory of the Simla season: "We used to reckon on three to four dinner parties per week, and the same with luncheon parties. It was a whirl of entertainment, interspersed with some quite gorgeous ceremonial and pomp, particularly in the Viceroy's house" (Plain Tales 144-45). Liveried rickshaw coolies shuttled their masters and mistresses around to these occasions in smart rickshaws bearing family crests. Amateur dramatics flourished ("eight to nine plays a season," Shimla Guide 3), as did polo, tennis, cricket and gymkhanas. Allen's fascinating Raj: Scrapbook of British India shows a publicity card for a moonlight gymkhana at Annandale, the recreation ground, with the last stanza of Longfellow's "The Day is Done" blazoned across the top: "And the night shall be filled with music, / And the cares that infest the day/ Shall fold their tents like the Arabs, / And quietly steal away." Printed under a beguiling sketch of the ground are the not altogether reassuring words, "Hon. Surgeon, Captain Rankin — An ambulance is available"(90). But the standard-bearers of Empire could take a few spills.

The best record of the Simla season in literature is provided by Kipling, for the trip was "a journey of delight Ruddy was to make many times" (Allen, Kipling Sahib 135), especially as a young reporter between 1882 and 1889. He loved not only the wonderful change in the air after the stifling plains, but also what he called the "life that fizzes in / The everlasting hills" ("An Old Song"). It inspired many of his best-known stories and poems. In fact, it is hard to imagine certain incidents in Plain Tales from the Hills (1888) happening anywhere else in the world — the devastating female archery tournament in "Cupid's Arrows," for instance, which is held under the deodars in Allandale, or the expiry of Mrs Schreiderling's old flame in his tonga in "The Other Man" (the corpse has to be tied in "lest he should fall out by the way" on the steep hillside). Nor perhaps could one of this book's most memorable characters, the mischief-making Mrs Hauksbee, have had full scope elsewhere. But then, according to the narrator in "The Education of Otis Yeere," one of the stories in Under the Deodars (also 1888), Simla was the place where "every right-minded story should begin." As for the poems, these evoke the atmosphere of Victorian Simla in a way that history never could, with the lighted rickshaws flashing past to "dinner, dance, and play" and the "revel on the height" going on into the early hours of the morning ("Possibilities").

Feeling themselves more than ever "members of one family, aliens under one sky" (Diver 33), the British closed in on themselves at Simla, let down their hair, and lived out their fantasy of upper-class home-counties' or Highland Britain — apparently with little thought for those who made their way of life possible. Yet the Indian princes and eventually even the wealthier middle-classes were putting more and more pressure on the local property market: A. O.Hume himself sought permission to sell Rothney Castle to an Indian ruler when he left for England. Nor could the denizens of the increasingly crowded and squalid Lower Bazar, who had caused the most unease during the uprising of 1857, be "kept in their places" indefinitely. Indeed, as Hume's own work suggests, crucial developments in the post-Imperial history of India were being decided in Simla itself. On show in the Viceregal Lodge, for example, is the table around which the first draft of Partition was made. Simla was, in many ways, a microcosm of colonial life, and also a seedbed of the collapse of Empire.

References

Allen, Charles. Kipling Sahib. London: Little, Brown, 2007.

_____. Plain Tales from the Raj. New Delhi: Rupa Paperback, 1993.

_____. Raj: A Scrapbook of British India, 1877-1947. London: Deutsch, 1977.

Diver, Maud. The Englishwoman in India. London: Blackwood, 1909.

Kanwar, Pamela. Imperial Simla. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Kipling, Rudyard. Collected Poems. Ware, Herts: Wordsworth, 1994.

Kipling, Rudyard. Plain Tales from the Hills. Available here (includes "Cupid's Arrows" and "The Other Man").

Kipling, Rudyard. The Works of Rudyard Kipling: One Volume Edition, available here (includes "The Education of Otis Yeere").

Shimla Guide with Map, 2007-08. New Delhi: Nest & Wings, 2007.

Last modified 14 March 2008