Sir William Hay Macnaghten, Bt. James Atkinson. watercolour, 1841. NPG 749 © National Portrait Gallery, London. Click on image to enlarge it.

The visitor to South Park Street cemetery in Calcutta (Kolkata) cannot but be impressed by the preservation of the colonial-era tombs. It is also a haven of peace and tranquillity in the midst of the bustling and often chaotic city. However a short walk from this gem is the Lower Circular Road cemetery and a very different prospect awaits. With a few notable exceptions the tombs and graves have been recycled for the Christian population of the city. I watched as a colonial tombstone was turned upside down to provide a cheap and simple memorial. Of course it makes complete sense. Many of India’s Christians are desperately poor and the colonial era was a lifetime ago.

Of the few eminent tombs that have survived is one near the entrance commemorating the life of Sir William Macnaghten and containing the few pieces of the Envoy which his plucky wife managed to recover from a pit in Kabul after surviving her own remarkable ordeal as a captive and hostage of the Afghans.

Two views of Macnaghten’s sarcaphagus in Calcutta. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Macnaghten, like many other Indian civil servants, came from an Ulster family. His father was a senior Judge in Madras. After being educated in England William travelled to India in 1809 armed with an East India Company cadetship and transferred to the Bengal civil service in 1814. He had brilliant linguistic skills and authored a number of works on jurisprudence. By 1830 he was working for Lord William Bentinck, the Governor General and from 1833 to 1837 headed the Political and Secret Departments in Calcutta. From 1837 he became one of the new Governor General, Lord Auckland’s, most trusted advisers. And yet, in spite of his reputation for wisdom and his knowledge of the region, Macnaghten played a key role in committing the East India Company and Great Britain to the reckless gamble of a war in Afghanistan.

“What? Lord William Bentinck was to exclaim when he heard that his successor had launched an army against Afghanistan. “Lord Auckland and Macnaghten gone to war? The very last men in the world I would have expected of such folly”.” (Macrory p.66). Contemporaries and historians are divided on the subject. Perhaps this was an eminent civil servant wishing to prove that he was also a man of action. Certainly Macnaghten was keenly aware of the plaudits and rewards that would flow from the imposition of British rule in Afghanistan and the denial of influence to the Russians. But it was a rash move. Remember that by 1839 the East India Company had not yet extended its control as far as Lahore, let alone Rawalpindi and Peshawar. Modern-day Pakistan was still largely under Sikh control and the passes into Afghanistan were controlled by the Pashtun and Baluchi tribes.

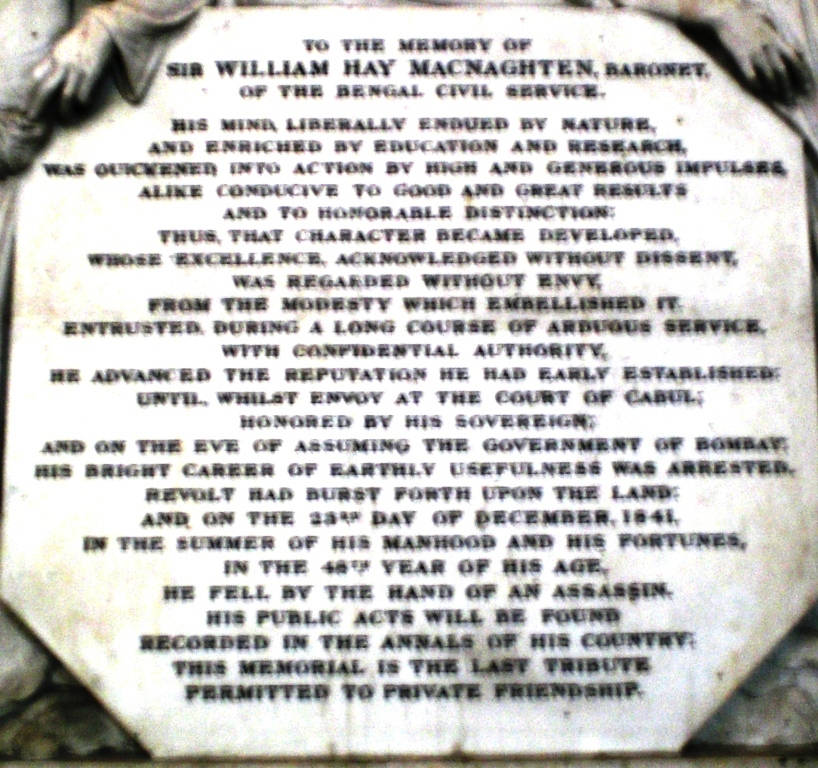

Left: McNaghten's memorial in St Paul's Cathedral, Calcutta. Right: The inscription on the tomb. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Nevertheless, as so often happens in military campaigns, the early days went well. Kabul was occupied in 1839 and Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk was placed on the throne in place of Dost Mohammed. But, by mid 1841, the British were in deep trouble. Their forces had been depleted and their commanders were old, infirm and inept. The plan was for the British to march back to India under a guarantee of safe passage from the Afghan tribal elders. However some of the local tribal chieftains were also plotting an insurrection in Kabul and it fell to Macnaghten as Britain’s Envoy to see if he could somehow play the chieftains off against each other, in a classic policy of divide and rule, and ensure the safety of the force and perhaps even of British rule in Afghanistan.

Macnaghten was already in contact with a number of chiefs when he made the fatal mistake of entering into negotiation with Dost Mohammed’s son, Mohammed Akbar Khan. Akbar had no reason to like or trust the British and he had a reputation for treachery. But Macnaghten was prepared to clutch at any straw and agreed to meet Akbar outside Kabul on 23rd December 1841.

Captain Mackenzie describes what happened.

About 12 o’clock Sir William, [Captain] Trevor, [Captain] Lawrence and myself set forth on our ill-omened expedition .... Close by were some hillocks on the further side of which from the cantonment the carpet was spread where the snow lay least thick and where the Khans and Sir William sat down to hold their conference .... After the usual salutations Mohammed Akbar commenced business by asking the Envoy if he was perfectly ready to carry into effect the proposition of the preceding night? The Envoy replied “Why not?”.... Suddenly I heard Mohammed Akbar call out “Begeer Begeer” (Seize, Seize) and turning round I saw him grasp the Envoy’s left hand with an expression on his face of the most diabolical ferocity. I think it was Sultan Jan who laid hold of the Envoy’s right hand. They dragged him in a stooping posture down the hillock, the only words I heard poor Sir William utter being “Az barae Khooda” (For God’s sake). I saw his face however, and it was full of horror and astonishment.” [Mackenzie quoted in Eyre, 164-66]

The formidable Lady Sale saw the later stages from her vantage point in the British cantonment “There was a great crowd about a body which the Afghans were seen to strip. It was evidently that of a European but strange to say no endeavour was made to recover it” (197). The following day (Christmas Eve) she commented in her diary ““All reports agree that both the Envoy’s and Trevor’s bodies are hanging in the public chouk [street]: the Envoy’s decapitated and a mere trunk; the limbs having been carried in triumph about the city” (198). She then “had the sad office imposed on me of informing both Lady Macnaghten and Mrs Trevor of their husbands’ assassination: over such scenes I draw a veil. It was a most painful meeting to us all” (198).

The rest is history. The British marched out of their cantonments in January 1842 on the long march to Jalalabad and thence to British India. On the way almost the entire force was massacred in the Khoord Kabul and Jugdulluk passes and then in the final stand at Gandamak. Some 120 prisoners, including Lady Macnaghten, Lady Sale, Captain Mackenzie and Lieutenant Eyre eventually survived a harrowing period of captivity, which included some severe earthquakes. Only Surgeon Major William Brydon survived to ride alone into Jalalabad (see painting below).

The Remnants of an Army Elizabeth Butler (Lady Butler). 1879. Oil paint on canvas. 1321 x 2337 mm. Tate Britian. Click on image to enlarge it.

Macnaghten’s role was subjected to a rigourous post-mortem. The eminent historian Sir John Kaye analysed Macnaghten’s actions in forensic detail (pp. 155-164), “Posterity may yet discuss the question, whether in those last fatal negotiations with Akbar Khan, Macnaghten acted strictly in accordance with that good faith which is the rule of English statesmen and for which our country, in spite of some dubious instances, is still honoured by all the nations of the East.” (p.159-160). This is cleverly worded by Kaye who is clearly hinting at Macnaghten’s duplicity. He adds, “If we regard the assassination of the British Envoy as a deliberate predetermined act it can only be said of it that it stands recorded as one of the basest, foulest, murders that ever stained the page of history.” (p164) but he then concludes that the murder was not premeditated but “one of those sudden gusts of passion”.

Lady Sale never minced her words about the official incompetence she witnessed at such close quarters in Afghanistan. However she was prepared to give Macnaghten the benefit of the doubt. She wrote “A fallen man meets but little justice; and reports are rife that the Envoy was guilty of double-dealing....[but] he only erred in supposing it possible that Akbar Khan, proverbially the most treacherous of all his countryman, could be sincere.”

In Afghanistan in 2002, shortly after the fall of the Taliban government, I met an Afghan descendant of Akbar Khan who greeted me with an emotional and heartfelt apology for his ancestor’s crime. This too was when our campaign was going well. It would look very different on my last visit in 2008 when, as in 1841, diplomacy was being used to fill in the gaps left by a creaking military campaign. My Afghan friend was still contrite but I consoled him. Macnaghten felt at home in the cut and thrust of diplomatic negotiation. I honestly doubt that he would have regarded his death as “one of the basest and foulest murders that ever stained the page of history”. The East India Company had, after all, invaded Afghanistan and tried to suppress its people. With failure and disaster seeming almost inevitable Macnaghten tried one last option; naked duplicity. Perhaps it was worth a try but he more than met his match in Akbar Khan. Nobody deserves such a brutal death but Macnaghten knew the penalty for attempting and failing at betrayal.

As for “his afflicted wife”, history has also been unkind. William Dalrymple shares the view of Lady Sale and Lieutenant Eyre that the Afghans did their best to look after the hostages and that they were agreeable companions. However “the prisoners were considerably less positive about some of their own number. Lady Macnaghten , who had somehow managed to save her baggage, but had refused to share any of her clothes or sherry, remained a figure disliked by all” (402).

Further reading

Dalrymple, William. Dalrymple. Return of a King. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Eyre, Vincent. Journal of an Afghan prisoner. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976.

Kaye, John William. History of the war in Afghanistan. 2 vols. London. WH Allen, 1874.

Macrory, Patrick. Signal catastrophe. London; Hodder and Stoughton, 1966.

Sale, Lady. A Journal of the disasters in Afghanistan. London; John Murray, 1843.

Last modified 31 July 2016