Introduction: According to the Dictionary of Mid-Western Literature (Vol. 1: The Authors, 2001), Hobart (Chatfield) Chatfield-Taylor was an American author, biographer, critic, editor — and European traveller. It is rather handy to have his American, outsider's view of late Victorian Gibraltar, where, typically, "Englishmen and Spaniards meet, but do not affiliate," even though some "anglomaniacs" try to imitate the former! Gibraltar is not properly described as a colony. Rather, it is one of Britain's Overseas Territories, and as such an integral part of the United Kingdom (see "Gibraltar and the British"). Nevertheless, Victorian Gibraltar seems to have been like a colonial outpost in miniature, with all the faults and idiosyncrasies of such a place — and a few of its very own.

Introduction, formatting. image scans and recent photographs by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source of the scans or the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them.]

IKE a lion couchant, slumbering with his shaggy head between his paws, lies ponderous Gibraltar. Waves splash lazily at its feet, fleecy clouds drift peacefully above its scraggy form, the warships of Europe ride pigmy-like at anchor beneath its towering sides; while puffing launches and swarms of white-winged feluccas dart to and fro between the rocky monster and the Spanish shore. Ships pass and repass, men of many nations come and go, the world moves on; yet silently this lion of England watches, the ever ready, ever alert, guardian of the Mediterranean.

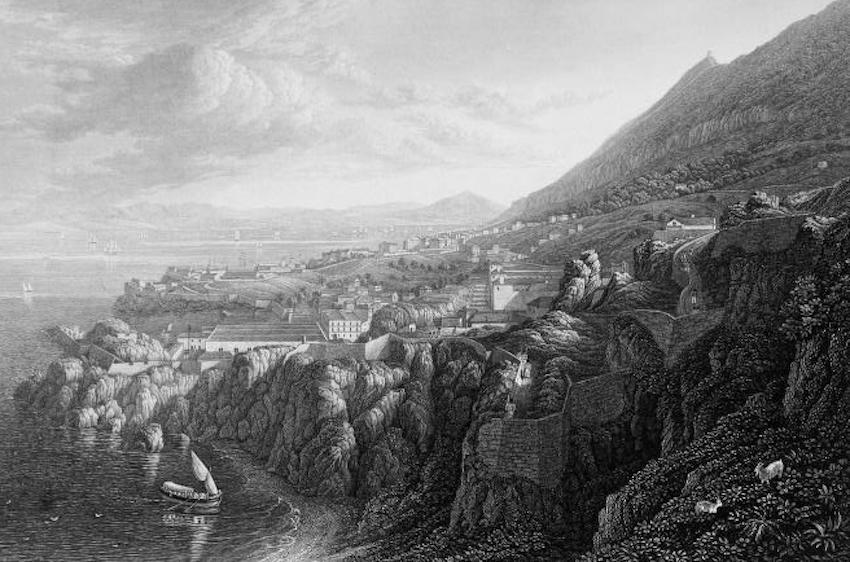

An early scene by Robert Batty: Gibraltar like a "lion couchant."

That is one's first impression of Gibraltar, when approaching from the sea; but as the ship draws nearer, and the cable rattles in the hawse-hole, the scene [236/37] is changed to one of life and action. Boats crowd about the steamer, ruffianly watermen jabber and gesticulate, whistles screech, and the faint notes of a bugle, or the roll of drums come from distant barrack yards. Perched in clusters along the water-front are the stuccoed houses of the Spanish town; beyond and stretching far out into the Mediterranean, the dull grey walls of ramparts and batteries, with here and there, and almost everywhere, little specks of red, marking the sentries on their beats.

Gibraltar is no longer a lion, but a monster hive of humanity, with its rocky sides honeycombed with galleries and casemates, where scarlet bees swarm, and dull drones toil. Through the years they have labored with chisel and blast; patiently and wisely they have built their hive, and woe to the bear who attempts to crush them; he will feel their sting.

How alien, how cosmopolitan is this [237/38] Gibraltar, a mere spur of rock, sticking like a thorn in the side of Spain, and yet not Spanish, or Moorish, or British, but rather a sourish leaven of Spaniard and Moor, with red English plums, dotted here and there, to give it a zest and flavor not its own. One forgets what a thoroughly detestable fellow the "rock scorpion" is, what an off scouring, without nationality, individuality or friend. The Spaniard despises the natives of "Gib," the Englishman scorns them, the stranger distrusts them, yet there are some twenty thousand of them, living there under martial rule, their actions regulated, their laws made and executed by a foreign power. A very good thing for them, too, as they are made to behave themselves, and keep themselves or at least their streets clean in a way that is unknown in neighboring Spain.

But the "rock scorpion" in all his entirety, is not to be seen from a steamer's deck. One must land at the water port and patiently await the arrival of one's [238/39] luggage to realize what a thorough blending of the east and west, time and foreign conquest have made of the Rock of Tarik.

No more cosmopolitan scene is to be witnessed in Europe than that presented at the water port. It is an ever-shifting panorama of strange humanity.

Olive-skinned watermen, with half-burned cigarettes between their lips, doze on the thwarts of their high-prowed boats, while swarthy peasants from Algeciras or Linea, with brilliant sashes and broad- brimmed hats, skin-tight trousers, and short braided jackets, come and go with the lazy air of Spain. Low-wheeled vans freighted with English beer or Chicago beef, rattle over the cobbles of the quay, while mules with jangling bells and gaily embroidered headstalls, struggle in the shafts of high-wheeled Spanish carts, and patient donkeys, their little bodies smothered beneath bulging panniers of straw, trot by unmindful of the shrill cries of their masters. [239/40]

What color; what variety! There are stately Moors with flowing robes of white, and high-bound turbans; thin savage Riffians, sleek padres with shovel hats and sombre gowns, dark-eyed women from Andalusia, their oily hair gracefully adorned with lace mantillas; barefooted urchins, tourists, stevedores, policemen, sailors of all nations, and soldiers of Spain, with smart Tommy Atkins, sturdy and erect, as only the British soldiers can be, standing guard over all.

Another early scene by Robert Batty: Gibraltar's "grey side studded with little houses."

The morning is calm and misty, not a ripple on the water, not a breath on the folds of the drying sails. Behind the gates and ramparts of the town the huge rock rises against the sky like the painted curtain of a theatre, its grey side studded with little houses, square and white as the toy houses of children, with here and there upon the hillsides tufts of scrubby foliage, cold and gaunt as the rock itself. Then, as the sun breaks through the mist, dew sparkles [240/41] on the green grass of the ramparts, the bayonets of the sentries glisten, smoke curls from the chimneys of the town, flags flutter, the colors on the hillside grow warm and brilliant, and the stirring notes of the fifes and drums break on the morning air.

Left: One of the Spanish houses in Gibraltar's narrow streets today. Right: An antique shop run by a firm established in 1870.

But that is only the landing stage, where the boats land from the ships at anchor in the bay. The town itself stretches along the western side of the rock for a mile or more in a series of narrow streets, where English signs and Spanish houses are mixed incongruously; where Englishmen and Spaniards meet, but do not affiliate.

There are the same stuccoed houses that one sees in Spain, white or delicate blue and yellow; the same graceful balconies and sloping roofs of tile, the same dingy little shops open to the street, the same bodegas at the corner, where groups of loiterers are gathered, drinking valdepenas or aguardiente, and all without the filth and many of the smells. [241/42] The English keep the town clean; they place English names upon the street corners; English signs and English goods are seen on every hand; red-coated English soldiers and red-faced English matrons mingle with the crowds which throng the streets; but the town and the people are as Spanish to-day as they were when the Prince of Darmstadt and Sir George Rooke attacked the rock by land and sea, and added another fortress to the spoils of England.

That was in 1704, during the war of the Spanish succession, when Spain was weak and imbecile, and all Europe was fighting for her crown. The garrison scarcely mustered a hundred men, but even this handful might have held out had it not been for some patron saint, whose festival happened to fall on the second day of the bombardment. The garrison thinking devotion the better part of valor, went to pray, and the place was surprised by scaling the eastern portion of the rock and attacking the [242/43] fortress from above. When the captors entered the town Darmstadt hoisted the Spanish standard, and proclaimed King Charles, but the admiral, with the voracity of the true Englishman, took possession in the name of the Queen of England.

It was a game of grab, not the only one nor the last which England has played, but it was successful, and there the redcoats have remained for nearly two centuries, by no other right than that of possession. In the meantime the Spanish officers at Linea date their letters from Gibraltar, with the parenthetical remark, that it is temporarily in the possession of the English, and Tommy Atkins, pacing his beat, gazes disdainfully across the barren strip of neutral ground at the dark-skinned sentries who guard the Spanish lines.

Present-day sign explaining the name and marking the place where the Moorish town once stood.

It was somewhere near this neutral ground, that Tarik, the one-eyed Moor, landed at the foot of the rock of Calpe, as the "Gib" was then called, when he came [243/44] in the year 711, with his little army of Arabs and Berbers to reconnoitre Gothic Spain. Tank's master, Mousa, the vali of Arab Tingitana, across the straits, had sent his one-eyed general, with an army of light horsemen, to burn and pillage, and then return to Africa, but the wily veteran saw the defenceless state of the enervated kingdom. Advancing boldly into Andalusia, he met King Roderic on the banks of the Guadalete near Jerez, and in spite of every disadvantage in numbers, position and supplies, he routed the effeminate army of the Goth and overran Spain. Tarik incurred the jealousy of Mousa, his chief. Conquest after conquest followed. The Moor in Spain is but a memory, but the name of the one-eyed victor still remains, where the conqueror of a later day looks down from the rock of Calpe upon the sunny plains and snow-capped siena of Andalusia. Gibel Tarik, meaning hill of Tarik, has been corrupted by successive ages and tongues into Gibraltar. [244/45]

All that is history, and of history there is a surfeit at the "Gib." There have been sieges and stormings galore, but the one the English most revere is the defense of "Old Eliot" in 1779, when for four years the rock held out against the united arms of France and Spain, and in spite of the floating batteries of d'Arcon, which "could neither be burnt, sunk nor taken," it still remains a British possession, garrisoned by a British force of six thousand men.

One confesses to a fondness for this British force. Wherever the English soldier finds his home there is color, life and smartness. With his forage cap perched aslant upon his close cropped head, his brilliant tunic buttoned to the chin with shining buttons of brass, his pipe clayed belt, and his "swagger stick," he walks the street with a mingled sturdiness and dash quite his own. His face is bronzed, and his hair is flaxen, his shoulders are broad and his eyes are keen, and seeing him one un-[245/46] derstands the remark of Napoleon, that "the British infantry is the best in the world; thank God there are so few of them."

One of the many pieces of ordnance that now serve an ornamental purpose on the "Rock." A sign explains that this one dates from Victorian times (the 1880s) and was one of three once cited on the South Bastion opposite it, looking towards the bay. The muzzle cover bears the crest of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps.

Gibraltar might be said to be in a continuous state of siege. The vigorous rules of a military post are never relaxed. The fact that it is a foreign post, held by force in a foreign country, is never forgotten. At retreat the gates are closed; at reveille they are opened. None but Englishmen are allowed to enter without a pass, and none but residents permitted to spend the night. The Spanish laborers from San Roque who come for the day are forced to leave at nightfall. A bell of warning clangs like an alarm of fire before retreat is sounded, and then the streets are thronged with grimy workmen from Spain men, women, even children, hurrying to get beyond the gates before the closing of the town.

At sunset the warden bearing the keys, marches through the streets to the stir- [246/47] ring strains of the fifes and drums or the braying notes of Highland pipes, and locks the gates for the night. Again at the hour of taps, martial music echoes through the town, as the pipers of the Black watch or the drummers of some regiment of the line, swing through the narrow streets, their red coats glinting in the lights which glare from shop or tavern, their feet falling in measured time upon the glistening cobbles of the pavement.

At night a city is at its best or worst according to one's point of view. Then the noises of the day are gone, the dirt is invisible, and harsh outlines or inharmonious colors are lost in sombre shadow. Gibraltar at night becomes completely Spanish. Men wrapped in the folds of graceful capas fill the streets, saunter idly in pairs or groups, unmindful of the existence of sidewalks; women and girls, with colored shawls of brilliant hues and mantillas on their comely heads, chatter and laugh in [247/48] the tones of Andalusia, while glasses chink in the bodegas, and from behind closed doors comes the click of castanets, the twang of a guitar. There are dingy highways, too, winding upward into the night, where paupers skulk, or dark skinned Cyprians squat in their doorways and cast languishing glances at stalwart Tommy Atkins, as he loiters toward the barrack yard.

In the main street is the "Cafe 1 Universal, "where at night the soldiers of the garrison and sailors of the fleets gather to drink their English beer; and natives of the town who ape their English masters assemble about the marble tables to chat and talk and pretend to be English. These anglomaniacs of the "Gib" are a curious type, they must be despised by both Spaniard and Briton, but they persevere in wearing covert coats, and English caps, in carrying bamboo sticks, and talking English with a soft lisp which is unmistakable. They are fond of fox terriers' and brilliant ties, [248/49] and the Cafe Universal seems to be their lounging place. This cafe is well named. It is the universal meeting ground of all classes of "Gib" society. The arms of many nations are painted on the walls where mirrors glisten, and the advertisements of Bass's Ale and Canadian whiskey, American hotels, or Spanish wines, mingle in cosmopolite confusion. There is a din of voices, the air is dense with smoke, canary birds chirp in their gilded cages, waiters of Spanish cast come and go or loiter by the tables, smoking their cigarillos with a familiarity which is truly Spanish; while here and there, mingling, with the dull black of civilian dress, are the dashing uniforms of the British soldiers, and at a table by themselves, a group of blue jackets from a Yankee cruiser, now half seas over, to remind one of the land across the ocean. Above the hum of voices rise the notes of a piano, while upon a platform placed to one side, dark girls from Malaga, dressed a la manola, [249/50] with brilliant scarfs of silk and roses in their hair, dance to the time of casta- nets, the sensuous dances of Southern Spain.

But all that is of the town and people, and the guide book says the town is uninteresting and dull. One forgets the mighty rock which towers above, frowning and grey, with its old Moorish castle perched like an eagle on a crag, with its chilly galleries chiseled and blasted in the limestone, where the mouths of cannons glare yawning from behind the cactus or palmetto, and the steps of the sentry echo. Scrambling through a rocky port one gazes down for full a thousand feet upon the harbor and the plain below. Dwarfish ships ride at anchor on the bay; a battalion, at extended order drill, is spread over the parade like little tufts of red upon a carpet of green velvet. Beyond are the race course and polo grounds where little ponies scramble like mice at play, and then the narrow strip of neutral land [250/51] stretches between the sea and the bay, where sentries pace and the sturdy Briton gazes defiantly at the sunburnt child of Spain. In the distance, across the blue water, the white walls of Algeciras and San Roque shine in the sunlight, and the green sloping hills and snow-capped mountains of Andalusia rise sharp against the fleecy sky. It is a view to be remembered.

The batteries of ponderous modern guns, and El Hacho, the signal tower, are now closed to visitors, so one no longer gazes, as at a former visit, across the straits to the misty hills of Morocco where the Moorish cities of Tangier and Ceuta nestle by the sea. You used to scramble on donkeys over the crest of the rock, and visit St. Michael's cave below; cockney gunners used to point the great guns at Africa, and detail their carrying power and caliber, but the authorities have grown suspicious, and now but half the "Gib" is shown to the foreign visitor, while even the where-[251/52] abouts of the newest batteries is kept a secret.

Brilliant flowers at the edge a of a garden on a narrow street.

After a visit to the galleries tunneled in the northern face of the rock, where antiquated cannon point in mere bravado toward the Spanish lines, you drive along the ledge-like road which runs a zig-zag way to the Alameda. Beside this road are perched the dainty little villas of the officers; trim Spanish houses, with English garden spots, behind grey walls of stone, where roses bloom and there is a sweet smell of jasmine. Neat English maids and ruddy English babies, smart pony carts and basket phaetons with Spanish servants in London liveries, remind one of foggy England. Here healthy girls with flat-soled boots and pink-faced officers in "mufti" stride along with a swinging step in striking contrast to the sauntering Spaniard. But there are the strings of meek-eyed donkeys with their swaying ears and the tinkling goat bells to [252/53] recall the south, and then the Alameda with its palms and cactus plants is reached. A park with geraniums and bowers, and tropical trees laid out with the precision of the English landscape gardener, this Alameda is the pride of Gibraltar. But there is only time for a glance at the shady paths and green waters for the spry Gibraltar pony is scrambling over the ground, and soon the little phaeton-like cab is whirling through the streets of the town again. Huge bastions with frowning guns barrack yards, where soldiers lounge upon the balconies military storehouses the governor's mansion, and tortuous lines of narrow street way, with quaint smoky houses and sloping roofs, pass in review. You meet Spanish "bobbies" in English clothes, and Spanish boys in Eton jackets, diminutive car-like 'buses with jangling bells upon the horses necks, huge carts drawn by oxen or mules, smart officers astride their Eng[253/54] lish mounts, and countless other sights, and then the show is over; the hotel is reached.

From a former visit of much longer duration, there are memories to add of officers' messes and clubs, tennis parties, dinners and visits, for an English garrison always makes a charming society. But all that is no more typical of the "Gib" than it is of Halifax, of Malta, or wherever the Union Jack is unfurled.

A last glimpse of Gibraltar.

The last glimpse of Gibraltar was from Algeciras across the bay. From there the rock looks as peaceful and sleepy as the fishermen who dozed in their boats.

A Carabinero, mounting guard, marched lazily to and fro upon the quay. His timeworn uniform was ill-fitting, his beard unshaven, but he was picturesque and typical of sunny Spain. He blended with the feluccas and the brigantines the beggars and the white washed [254/55] houses, and made it difficult to realize that across that stretch of water, where the white sails glared in the sun-light was a mighty fortress, with bastions and guns, with galleries and batteries, where the flag of England fluttered and the Highlander was piping the war-songs of his island home.

Related Material

Bibliography

Batty, Lieut. Col. Robert. Select views of some of the pricipal cities of Europe from original paintings by Lieut. Col. Batty F. R. S.. London: Moon, Boys & Graves, 1832. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 8 January 2019.

Chatfield-Taylor, Hobart Chatfield. "Gibraltar." The Land of the Castanet: Spanish Sketches. Chicago: Herbert S. Stone & Co., 1896. 236-254. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 8 January 2019.

Created 8 January 2019