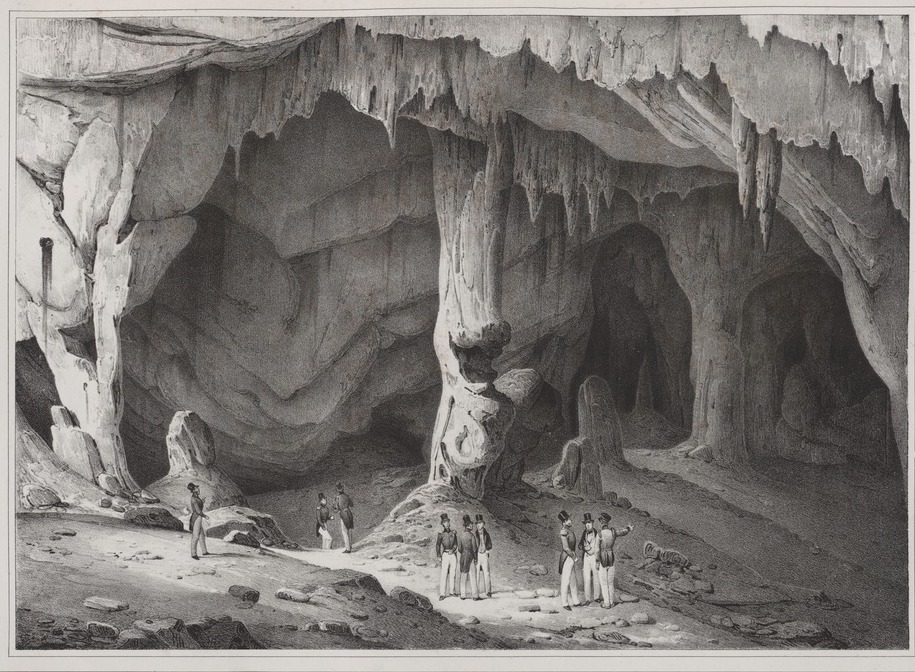

St Michael's Cave, in the Upper Rock Nature Reserve, Gibraltar. Source: D'Urville, no. 11. This has always been a source of wonder for tourists. The U.S. Navy's handbook explains

Due to the limestone formation of the Rock, there are many caves — the largest of which is St. Michael's. It is 1,000 feet above sea level, and can be entered only through a small opening. Within is a lofty hall, 250 feet long, 90 feet wide, and 70 feet high. Stalactites produce the impression of a Gothic cathedral. Leading from this large hall are numerous small caves, in which fossil remains have been found. Great labor and a large amount of money have been expended in attempting to penetrate all of these caves, but up to the present time many of the minor ones have remained unexplored. [Ports of the World, 19-20]

Here is another, more dramatic account of it, by a mid-nineteenth-century travel-writer and artist William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854). He and his son ventured into the cave along with a guide, armed with blue lights from the Signal station:

we descended the slippery pathway between lofty pillars of stalactite ... and ... found ourselves in a darkness visible, and in a silence so deep and still that the droppings of the water which percolates through the roof above were distinctly heard plashing at intervals upon the rock beneath. Our guide lighted a heap of brush, which, as it blazed up, dimly disclosed to us a lofty vault-shaped dome, supported as it were on pillars of milk-white stalactite, assuming the appearance of the trunks of palm-trees, and a variety of fantastic foliage, some stretching down to the very flooring of the cavern, others resting midway on rocky ledges and huge masses of congelation, springing from the floor, like the vestibule of some palace of the genii. At a given signal the blue lights were now kindled, when the whole scene, which before had been but imperfectly illuminated, flashed into sudden splendour,— hundreds of pendulous stalactites before invisible started into view,— the lofty columns, with their delicate and beautiful formation, glittered like silver, and seemed raised and enchased by the wand of enchantment. But this glimpse of the splendours of the cavern was, alas, but momentary; for our lights speedily burning down, we were compelled to retreat before we were involved in dangerous darkness.... [172-73]

Much has happened since the Bartletts' visit. After the cave floor was concreted over, the space which once sheltered our most ancient ancestors became a war hospital in World War II. It is now used for staging concerts and shows, the stalactites and stalagmites routinely illuminated by coloured flashing lights. The cave's lower segment, however, which was discovered only in the twentieth century, remains largely unspoiled — for those bold enough to make the expedition (see Rushton 22-23).

Text and image acquisition by Jacqueline Banerjee. You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Bartlett, William Henry. Gleanings, Pictorial and Antiquarian, On the Overland Route. 2nd ed. London: Hall, Virtue, 1851. Google Books. Free ebook. Web. 27 January 2019.

Rushton, Katherine. Gibraltar. 2nd ed. Peterborough: Thomas Cook, 2011.

d'Urville, J-S-C. Dumont. Voyage de la Corvette l'Astrolabe exécuté par ordre du roi: pendant les années 1826-1827-1828-1829. Paris: J. Tastu, 1830-35. New York Public Library Digital Collections. ID. no b13624459. Web. 27 January 2019.

U.S. Navy: Ports of the World. Washington: US Government, 1920. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 27 January 2019.

Created 27 January 2019