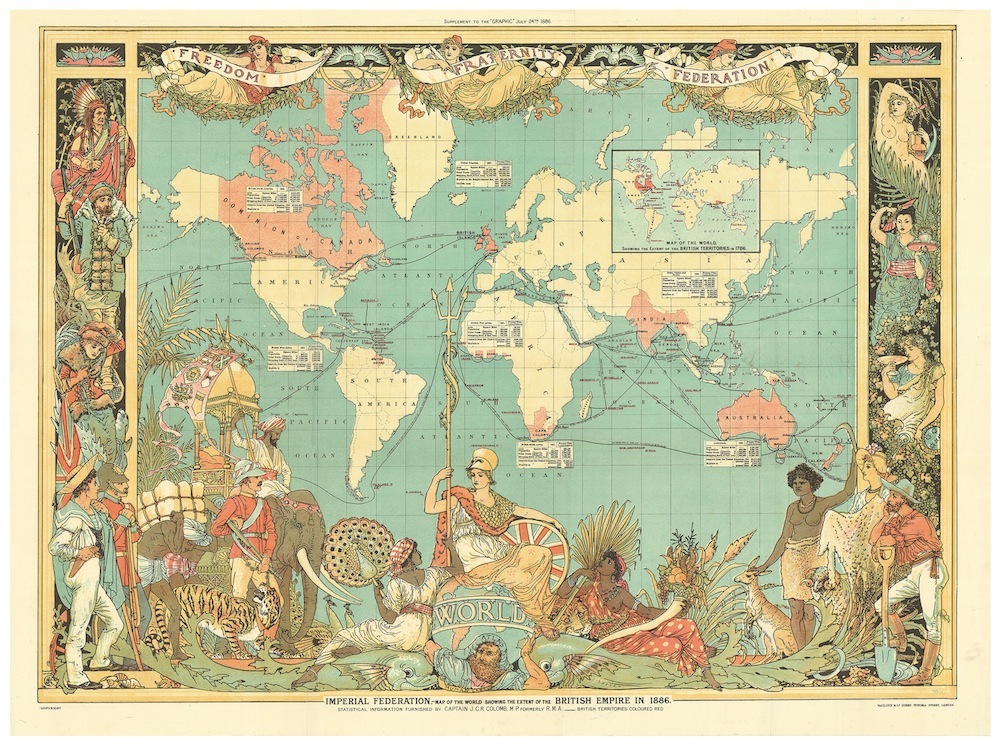

Imperial Federation: Map Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886, designed by Walter Crane. Colour lithograph, published by Maclure & Co. as a supplement to The Graphic, 24 July 1886. [Click on the image to enlarge it, and for more information about it.]

Best known now for his role in the provision of universal elementary education in 1870, the liberal politician William Edward Forster (1818-1886) was also instrumental in forming the Imperial Federation League of 1884. He chaired a meeting "in furtherance" of it at the Westminster Palace Hotel on 18 November 1884 (adjourned from an earlier one of 20 July that year) at which the various proposals for it were spelled out. First and foremost, the object of the league would be "to secure by federation the permanent security of the Empire." There would be no interference with the rights of the individual parliaments, but the different countries involved "should combine on a equitable basis the resources of the Empire for the maintenance of common interests, and adequately provide for an organized defence of common rights." There were other proposals as well — that it should be cross-party, that branches should be set up in the various countries, and so forth ("Conference of Imperial Federation").

This was a response to the thinking of the time. The early part of this decade was, suggests David Cannadine, "a pivotal time in Britain's imperial history," when:

[w]ith the generally reluctant acquiescence of the men in London, the empire was expanding more rapidly than ever; but it was also facing unprecedented nationalist challenges, in Ireland, Egypt and India, which might portend an imperial "disintegration" to parallel and reinforce the one that Lord Salisbury feared at home. [421]

Lord Salisbury's essay, "Disintegration" (1883) had, in fact, been followed by an influential book by the Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge, Sir John Seely (1834-1895). In The Expansion of England: Two Courses of Lectures (1884), Seely had made it clear that Britain's empire could by no means be taken for granted:

We are not then to think, as most historians seem to do, that all development has ceased in English history, and that we have arrived at a permanent condition of security and prosperity. Not at all; the movement may be less perceptible because it is on a much larger scale; but the changes and the struggles when they come — and they will come — will be on a larger scale also. And when the crisis arrives, it will throw a wonderful light back upon our past history. All that amazing expansion which has taken place since the reign of George II, and which we read of with a kind of bewildered astonishment, will begin then to impress us differently. At present when we look at the boundless extent of Canada and Australia given up to our race, we are astonished, but form no definite opinion. When we read of the conquest of India, two hundred millions of Asiatics conquered by an English trading company, we are astonished and admire, but.... Time will reveal what was really solid in all this success, and what was not so. [195-96]

Yes: only time will tell, he continues, whether

a great and solid World-State has been produced, or that an ephemeral trade-empire, like that of old Spain, rose to fall again; either that a solid union between the West and East, fruitful in the greatest and profoundest results, was effected in India, or that Clive and Hastings set on foot a monstrous enterprise which, after a century of apparent success, ended in failure. [196]

Seely's students and readers alike could not but feel that efforts must be made in order to avert such a failure.

At first, and for a limited period, the new bid by Forster and others to promote consolidation did seem to bear fruit: "The League spawned branches in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the West Indies, and it was supported in Britain by Conservatives, Unionists and Liberal imperialists." However, "when it tried to move from vague objectives to particular policies, it fell apart and was dissolved in Britain in 1894" (Cannadine 421).

Yet the idea of an Imperial Federation had some positive results:

for it was the League that had called for the first conference of colonial prime ministers at the time of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887. The conference duly took place, attended by more than one hundred delegates, from both the self-governing and dependent colonies (although India was not represented). It was only a deliberative body, and its resolutions were not binding. But the colonies in Australia and New Zealand did agree to pay £126,000 per annum towards the cost of the Royal Navy, to help fund its deployment in the Pacific, and in return the British government agreed not to reduce the navy’s Pacific Station without the consent of the colonies. The conference also approved a proposal to lay a telegraph cable between Canada and Australia, the final link in an imperial network of communication encircling the globe. [Cannadine 421]

Moreover, that first conference of colonial prime misters led to other such meetings. A second colonial conference, though on a smaller scale, took place in Ottawa in 1894, and Joseph Chamberlain presided over a further two in London in 1897 and 1902. Meetings continued, and indeed the idea of a federation itself refused to die:

During the Edwardian years and beyond, the Round Table and other British imperial advocacy groups continued to campaign on behalf of Greater British unity. The imperial federalist project reached its zenith during the First World War with the creation of an Imperial War Cabinet in 1917, which incorporated the prime ministers of the dominions. This was the nearest the dream of a politically unified Greater Britain came to fruition. [Bell 196]

We can see this with hindsight, but, as late as 1921, federalism was still being touted as a way of bringing about "a closer coöperation in purely imperial matters, between the United Kingdom, the Dominions, and India without sacrificing the principles of democracy or encroaching unduly on the field of local autonomy" (Smith 274).

What happened instead was that the empire did disintegrate, and the "Commonwealth of Nations" emerged, almost by happenstance, with the Commonwealth Imperial Conferences being replaced by Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences (see Palmer 127). Such a result was far from what Forster and others had hoped for. On the other hand, if twenty-first century Britain's close bonds with other members of the Commonwealth owe something to the late Victorians' Imperial Federation League, that is still no mean outcome.

Bibliography

Bell, Duncan. Reordering the World: Essays on Liberalism and Empire. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Cannadine, David. Victorious Century: The United Kingdom 1800-1906. London: Allen Lane, 2017.

"Conference On Imperial Federation." The Times. November 19, 1884: 6. Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 May 2018.

Palmer, Alan. Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British History. 5th ed. London: Penguin, 1999.

Seely, John Robert. The Expansion of England: Two Courses of Lectures. Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1905. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 11 May 2018.

Smith, William Roy. "British Imperial Federation." Political Science Quarterly. 36/2 (June 1921): 274-297.

Created 11 May 2018